“By the Wrath of God.” Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Queen with Ambition

A Brief Synopsis: Medieval Queenship

Eleanor of Aquitaine was a force to be reckoned with, but, as ex-Queen of France, Queen of England, and heir to one of the richest resources on French soil, the Duchy of Aquitaine, controversy surrounded her image. Her contemporaries and historians alike are divided on whether she was extraordinary or troublesome. Yet, it is indisputable that she was a fascinating figure, and will suffice as a brilliant example to enlighten readers about the influential and powerful women that dominated the medieval landscape.

Setting the Context: Welcome to the Middle-Ages

To enter the world of Eleanor, it is important to grasp an understanding of her contemporary period. Twelfth-century England and France were different landscapes that were broken up into feudal-like systems. Local counties such as Poitiers and Toulouse in France were separate units which paid homage and allegiance to the king. A lord-vassal relationship composed much of the power structures, which flowed in a web from the top (the king) through his nobles and barons, to officers and local sheriffs, who would dispense justice on the king’s behalf.

Identity and community were invested in local areas as opposed to a national identity, which did not exist as to how we understand it today. This was especially the case in England, where the north was detached from the south, and acted as the seat of kingship after the end of the Norman dynasty with the death of Henry I. Rulership was precarious with a succession crisis, to which Eleanor and her second husband Henry Plantagenet were tasked with stabilising a country with dynamic and changeable authority. The key thing to understand from this was the element of individuality which counties retained, such was the case for Aquitaine, the most notoriously unruly and autonomous of provinces.

Propelled into Royal Power: France

Eleanor inherited the duchy upon her father William X’s death in 1137, at fifteen years of age. She quickly became desirable for political marriages throughout Europe, but Louis VII of France was the one to wed the duchess in 1138. However, Eleanor’s strength of character was incompatible with Louis, often complaining it was as though she was married to a monk.

The French court was also dismissive of Eleanor’s strength of will and intellect, often accusing her of incestuous affairs with her uncle Raymond of Antioch. Certain rumours went as far as to claim that, on the Second Crusade, she slept with the Muslim ruler and target of crusading animosity, Saladin.

As queen of France, Eleanor was stifled and miserable, married to a king who would barely visit her bedchamber and a northern court suspicious of a strange southern consort. It all resulted in Eleanor seeking prospects elsewhere, leading her to Henry Plantagenet.

Propelled into Royal Power: The Angevin Dynasty (Plantagenet England)

After her marriage to Louis was annulled on grounds of consanguinity (sharing a common ancestor), Eleanor married the future king of England on 18 May, 1152 – scarcely two months after her annulment. Her decisiveness in seeking a new husband demonstrated Eleanor’s political noose. Realising her vulnerable position should she remain unmarried, she ensured for herself a marriage that would be equally or more ambitious than her previous one. By marrying Henry Plantagenet, Eleanor secured her fate on her own terms. Once he had claimed his throne and established his rule, the royal couple asserted their authority over their new realm in England.

Eleanor held political agency with advice she offered to Henry II. She involved herself in issuing a multitude of charters as well as successfully achieving her dynastic duty in full by providing Henry with six sons and three daughters. Eleanor’s attention was invested in her favourite son Richard, who she shaped as the heir of her duchy. Her ambition for her son extended so that she helped in inciting a rebellion against her husband in 1173, in which Henry’s sons united against their father in complaint of unfair allocation of inheritance and political authority. For the remaining decade of Henry II’s rule, Eleanor was imprisoned: her betrayal infuriated the king and destroyed their marriage. Henry even sought the same annulment as Louis, but his claim was never granted.

Eleanor’s position was thus placed in jeopardy once again, threatened once more as she had been a few decades before when divorced by Louis. Yet, once again Eleanor proved her entitlement to power was not something she would let slip through her fingers.

Commanding Royal Power: A Lady of Legend

It was in the latter stages of Eleanor’s life when her power bore most fruit. When her son Richard inherited the throne upon Henry’s death in 1189, Eleanor became far more politically active; at sixty-seven she emerged from captivity, eager to grasp the reins of governing under her sons. Her “remarkable sagacity” and wise statesmen-like judgement impressed her contemporaries, to such an extent that, whilst Richard was participating in the Third Crusade, Eleanor took on the role as regent once more. Even the king’s designated chancellors, Hugh de Puiset and William Longchamp, who ran the country in Richard’s stead, would adhere to the Queen’s advice. Her political agency was also something John relied upon when succeeding after Richard’s death. It was under her networking that John gained support as the king against his rival claimant, Arthur of Brittainy. Through charters that accorded rights to the nobles of Aquitaine, and to the inhabitants of the towns and religious establishments, Eleanor gained their support for John.

Eleanor throughout her career gripped tightly to her entitlement to Aquitaine, and her success in governing is reflected in the extraordinary growth and prosperity of many towns and cities within the duchy under her nurturing. Her firm assertion of her right to Aquitaine was reinforced by its prosperity, and showed she was more than capable of taking charge of the infamously unruly duchy.

Eleanor was herself extraordinary, as she took full advantage of the authority she was given and pushed the boundaries with what she could achieve within them. Sometimes, in the case of the 1173 rebellion, she pushed too far out of the medieval boundaries set for women in which she reaped consequence for, but by no means was she ever defeated by the hurdles thrown in her path. She persisted in her determination to cling onto power that was rightfully hers, whether that be her birthright inheritance with Aquitaine, her role as a wife, her role as a queen, or her role as a mother. From Eleanor, we learn that women in medieval Europe did in fact have opportunities at power, they just had to be clever in maximising their authority and having the determination to persist and keep it.

Questioning Exceptionality: Was Eleanor Unique?

It is an easy mistake, however, to misunderstand the exceptionality of Eleanor. Modern outlooks often miss the nuance regarding the role of medieval women by assuming that, outside of the present, women were completely squashed by patriarchal structures. Not that this was a false generalisation, but one that misses the complexities of rulership in the Middle Ages. It was indeed common for a woman of status and considerable social standing to exercise power, especially a king’s wife or mother.

Historians Ayaal Herdam and David J. Smallwood explains this concept well, discussing that “the mechanisms of kinship and property in medieval Europe could in fact propel women of an aristocratic elite into positions of great power.” This can be built upon by considering examples of royal women in positions of power; often a source of wisdom and advice for a king, royal women held considerable power within court.

A contemporary example of this is Empress Matilda, who contested her rights to the throne in the aforementioned succession crisis after her father Henry I’s death. Once her son, Henry Plantagenet, had seized the throne from his cousin King Stephen, Matilda also played an influential role in Henry’s decision making as the king’s mother. Another example earlier in the medieval period was Emma of Normandy, wife of Aethelred II and Cnut, and mother to Edward the Confessor; it was her backing of her sons that ended up being key in the decisions for succession in the eleventh century.

The authority that Eleanor wielded under her husband’s and son’s reigns was not exceptional to medieval royal women. It does, however, show how women were not completely dismissed as being as inferior as modern standards might assume. Something that draws attention to Eleanor is how far she was willing to go to exercise full authority and take full advantage of the positions of power she was given. As Herdam and Smallwood say, women could be propelled into positions of power, but they are only powerful and remain memorable if they are able to stand up to the task and have the grit to wield and maintain their power. This is what made Eleanor so captivating and exceptional.

Interpretation: Historical Thought on the Queen

Historian Gabrielle Storey has made a compelling argument discussing the misinterpretation of Eleanor in the 1968 film The Lion in Winter, which played into the mythology surrounding the queen. These myths are the ‘Black Legend’ claiming Eleanor was a sexually scandalous woman, and the ‘Golden Age’ claim that she was a troubadour overseeing a court of love. It is an interesting outlook regarding modern media’s portrayal of historical events often being altered for entertainment purposes.

Storey’s framework can be applied to historical thought on the queen throughout history, with each chronicler and writer crafting Eleanor’s image to suit their respective contemporary societies.

Chronicler Richard Davizes claimed Eleanor as an “incomparable woman,” proving her contemporaries could recognise the queen for her political skill. Yet in her youth and after her death, due to the breakdown of the Plantagenet empire and the dire reputation of John, chroniclers jumped at the opportunity to display Eleanor as scandalous and promiscuous. The queen was painted in a negative light when it was socially convenient. Intellectuals of Thomas Becket’s entourage blamed, in part, Eleanor’s nefarious influence over her husband for the deterioration in his relationship with the archbishop. Additionally, churchmen close to Henry II saw Eleanor as the main inspiration for the 1173 uprising. The misinterpretation of the queen in the medieval period created, in Eleanor, a scapegoat.

Even Shakespeare interpreted Eleanor as the monstrous injurer of heaven and earth in his history play on King John. More implicitly, his portrayal of Lady Macbeth in his play Macbeth proved that queen consorts as advisors to their husbands were villainous and overzealous. Women who aimed to usurp their power boundary between them and their husband were therefore considered a threat towards the Jacobean natural order.

Literature and film also are not the only media outlets to feed into myths and falsities around Eleanor. The art piece Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, by Frederick Augustus Sandys (1858), depicts the queen delivering poison to one of Henry II’s mistresses, Rosamund Clifford. This supplements the aforementioned ‘Golden Age’ myth as a romanticist piece that indirectly portrays her as jealous and calculated. It applies nineteenth-century ideals by focusing on courtly love in the Middle Ages, a period the Romantics were eager to idealise, as well as obscuring the contemporary dynamics between queen consort and mistresses.

Throughout historical writing, Eleanor has been framed in an image that fits the social framework of the time. Considering such, this discussion challenges its readers to place themselves exclusively in Eleanor’s own context, instead of applying our own, as to make our understanding of the queen less distant and obscure.

Conclusion

Evidently, Eleanor serves as an intriguing case study into understanding the dynamics of medieval courtly power and the roles of women in supporting the king and administering the realm. It provokes the reader to consider the exceptionality of medieval queens without applying modern opinion or standardisation. Eleanor’s example proved that positions of power for medieval women were not unique, but it was her ability to assert her rights to power and inheritance, while remaining consistent and determined, that made Eleanor such a distinctive historical individual.

Written by Kirsten Pierrepont

Bibliography

Aurell, Martin. “Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Art of Governing.” In Norman to Early Plantagenet Consorts. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2023.

Bartlett, Robert. “Blood Royal Dynastic Politics in Medieval Europe.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Bevington, David. “King John, Britannica.” Added Jul 20, 1998. King John | Shakespeare’s History Play & Legacy | Britannica.

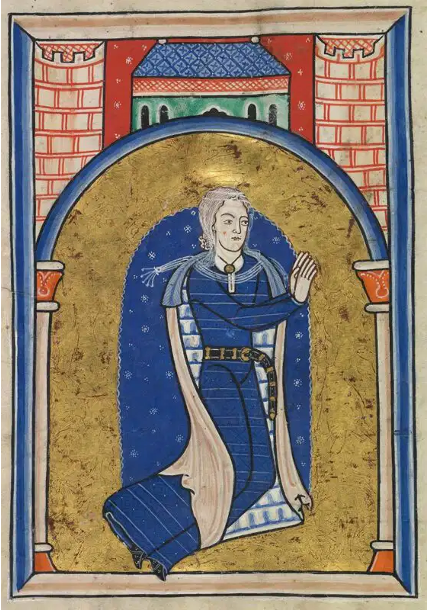

“Donor Portrait in Psalter of Eleanor of Aquitaine.” 1185, via the National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague. Eleanor of Aquitaine: The Queen Who Chose Her Kings | TheCollector.

“Effigies of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England in the church of Fontevraud Abbey.” Image credit: Adam Bishop / CC. How Did Eleanor of Aquitaine Become Queen of England? | History Hit.

Herdam, Ayaal, and Smallwood, David J. “THE QUEEN FROM THE SOUTH Eleanor of Aquitaine as a Political Strategist and Lawmaker.” Strategic Imaginations Book: Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture, Leuven University Press, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1bd4h91.9.

Jones, Dan. “The Plantagenets: the Kings who made England.” London: Harper Collins Publishers 2012.

“Map of the Angevin Empire.” INTERNATIONAL: Ireland in the Angevin empire – History Ireland.

“Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine.” By Frederick Augustus Sandys. Oil on canvas, 1858. From the National Museum Wales. Sex & The Citadel: Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Courtly Love Myth | All About History.

Storey, Gabrielle. “(Mis)Representing Queens: The Untold Lives of the Empress Matilda and Eleanor of Aquitaine.” Parergon 39, no. 1 (2022). Gale Literature Resource Center (accessed February 7, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A711558607/LitRC?u=uniyork&sid=summon&xid=529e7dbf.

Weir, Alison. “Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God, Queen of England.” London: Pimlico, 2000.