Meaning within Miscellany: The Value of Late Medieval Commonplace Books

Described by researcher Ralph Hanna as an “oscillation between the planned and the random,” medieval commonplace books contained a variety of items written by one or more compilers. These books are fascinating sources that provide a glimpse into life in late medieval England. From financial records to medical recipes to popular poetry, commonplace books encompassed a multitude of themes within one manuscript.

Laura Flannigan.

In general, book production and literacy grew in the late medieval period, and the proliferation of manuscripts increased. This growth was rooted in the expansion of bureaucratic processes, lay demand for devotional literature, and pragmatic demands, including commerce, legal professions, and estate administration. Commonplace books were part of this growth and they reveal information about the compilers’ business, religious and devotional practices, as well as interest in popular literature, to name a few areas. These texts are also referred to as “miscellanies” and “assemblages.” Ownership of commonplace books was typically associated with the medieval “middling classes,” because access to the materials and information to compile such texts required a certain level of wealth.

Commonplace books contained text fragments, from accounting details to pen trials to poetry. This variety indicates the wide-spanning literary interests of the compilers and owners of the texts. Commonplace books often belonged to specific households, but they could also be shared within a community. Not only could texts be lent to others in the community, but the practice of reading aloud enabled the sharing of information regardless of the literacy of the listeners. This practice reflected the diverse and nuanced forms of literacy that occurred in the period when literacy could augment orality.

Historians such as Arthur Bahr and Seth Lerer debate the aspects of intentionality and wider meanings to these assemblages of text, with individual compilers and readers finding different meanings within their pages. Commonplace books can be interpreted as the process by which the compiler curates a purposeful text, a library In Parvo (“in miniature”), which held varied texts and were selected to reflect wide interests. Building on this idea of the text as a miniature library, historians can use these sources as a “window” into the lives and communities of late medieval Britain. They reveal more about the period’s literate communities, literary cultures, and the perspectives of the compilers.

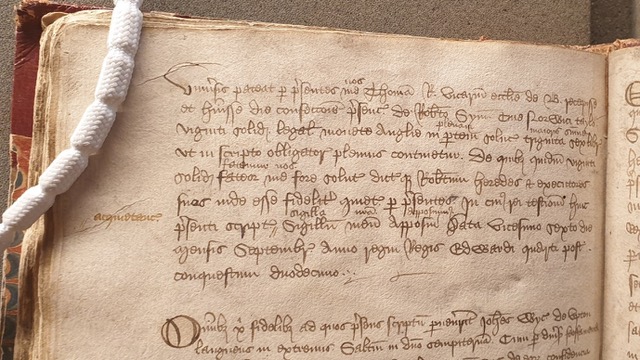

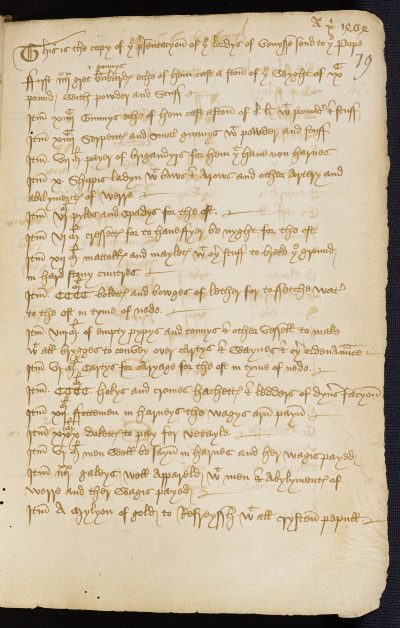

An intriguing example of this type of source is The Commonplace Book of Robert Reynes of Acle, found in the manuscript Tanner MS 407, which is currently held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford. This late 15th-century manuscript featured varying texts, from business records to a local play script, compiled into a fascinating collection. The manuscript incorporated religious, legal, financial, commercial, medical and literary themes. Reynes’ commonplace book is an example of the multilingualism of the period, and is ‘macaronic,’ meaning it combined vernacular languages and Latin. In this case, Middle English, Latin and Old French were used in various entries. The macaronic nature of commonplace books indicates that medieval communities’ literary interests were not only in the vernacular, but also spanned diverse languages and genres rooted in, as researcher Rory Critten writes, a “pan-European network of textual transmission.”

Due to the oral culture of late medieval England, information and literature were shared verbally through social networks. Robert Reynes, the owner of this commonplace book, likely played a key role in his community in Norfolk, bridging the gap between literate and non-literate individuals. A figure in the community such as Reynes’ could read aloud passages from the commonplace book to share with the wider community. His compilation therefore indicates not only his personal interests but also the interests of his community and social network.

Other examples of miscellanies from the period include the commonplace books of Richard Hill and John Colyns. Richard Hill’s text contained a wide range of literature popular at the time, whereas John Colyns’ focused more on his own practical affairs. Similar types of miscellaneous text produced in this period were folded almanacs, which combined calendars with medical and astronomical information for readers. They were small texts typically designed to be hung from a belt. Almanacs offer us greater understanding of medieval medical practice and the variety of texts utilised by medical practitioners. Like commonplace books, historians can find the meaning within the varied nature of almanacs.

Compilations like these reveal the often practical nature of late medieval literacy, but also display eclectic tastes of compilers. The extent to which we can view these books as entirely miscellaneous or intentionally curated is subjective. Through viewing the texts as a library in Parvo, we can conceptualise the texts as reflecting medieval interests in practical areas and beyond.

Commonplace books have left an interesting legacy which has continued into the early modern and modern eras. Even now we see the phrase live on, with the term used online in blogs and popular newspapers such as The New York Times, despite the wildly different landscape of literacy and information. Modern commonplace books record poetry, songs and quotes that stand out to the compiler, and the modern form is similar to journaling and scrapbooking. The compilers of commonplace books, whether medieval or modern, find value in curating and collecting a breadth of information and literature. A New York Times journalist wrote of the “meaningful” nature of her compilation, illustrating the continuing merit of the commonplace book form in our modern, digital world. Commonplace books are distinctly personal texts which reveal the perspectives, tastes, and interests of the compilers, no matter the era in which they are created.

Written by Amelia Spanton

Bibliography

Images:

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Tanner MS 407, folio 41. Photo: https://listology.blog/2020/07/07/a-venetian-wish-list-of-1464.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Tanner MS 407, folio 52v. Photo: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/d54cd0f2-60a3-400f-b1f7-3fab3aac42cb/#.

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, Tanner MS 407, folio 58v. Photo: https://manyheadedmonster.com/2024/04/30/commonplace-legal-knowledge-in-fifteenth-and-sixteenth-century-england/.

Historic England, Church, Acle, Norfolk. Photo: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1372674.

Primary sources:

Reynes, Robert. The Commonplace Book of Robert Reynes of Acle: An Edition of Tanner MS 407, edited by Cameron Louis. New York & London, Garland Publishing, Inc.: 1980.

Secondary sources:

Bahr, Arthur. “Miscellaneity and variance.” In The Medieval Manuscript Book, edited by Michael Johnston and Michael Van Dussen, 181-198. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Boffey, Julia and John J. Thompson. Book production and publishing in Britain, 1375-1475. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1989.

Carey, Hilary M. “What Is the Folded Almanac? The Form and Function of a Key Manuscript Source for Astro-Medical Practice in Later Medieval England.” The Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 16 no. 3, (2003): 481–509.

Clanchy, M. T. From memory to written record: England, 1066-1307. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Critten, Rory G. “The multilingual English household in a European perspective: London, British Library MS Harley 2253 and the traffic of texts.” In Household Knowledges in Late Medieval England and France, edited by Glenn D. Burger and Rory G. Critten, 219- 243. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019.

Collier, Heather. “Richard Hill – A London Compiler.” In The Court and Cultural Diversity, edited by Evelyn Mullally and John Thompson, 318-329. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1997.

Fox, Adam. Oral and Literate Culture in England, 1500-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hanna, Ralph. “Miscellaneity and Vernacularity: Conditions of Literary Production in Late Medieval England,” in The Whole Book: Cultural Perspectives on Medieval Miscellany, edited by Stephen G. Nichols and Siegfried Wenzel, 37-51. Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Kohen, Thomas. “Commonplace-book communication: Role shifts and text functions in Robert Reynes’s notes contained in MS Tanner 407.” In Communicating Early English Manuscripts, edited by Paivi Pahta and Andreas H. Jucker, 13-24. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 2011.

Lerer, Seth. “Medieval English Literature and the Idea of the Anthology.” PMLA : Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 118, no. 5 (2003): 1251-267.

Parker, David. “The Importance of the Commonplace Book: London 1450-1550,” Manuscripta 40, no. 1 (1996): 29-48.

Parkes, M. B. Scribes, scripts, and readers: studies in the communication, presentation, and dissemination of medieval texts. London, Hambledown Press: 1991.

Youngs, Deborah. Humphrey Newton (1466-1536): an early Tudor Gentleman. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2008.

This is a very interesting piece – I love the idea of medieval miscellanies as libraries ‘In Parvo’, and it reminds us that books from the past did not necessarily take the form we’re used to today. What does it say about the kinds of material Robert Reynes must have had access to, notwithstanding his relatively humble status?

Incidentally, it’s nice to see my image cited in a York Historian article, since I was on the founding editorial board! Keep up the good work everyone.

LikeLiked by 1 person