Heart of the Forest: The Freeminers of the Royal Forest of Dean

“Here, queen of forests all, that west of Severn lye,

Her broad and bushy top Dean holdeth up so high,

The lesser are not seen, she is so tall and large,

And standing in such state upon the winding marge…

So fruitful in her woods, and wealthy in her mines.”

– Michael Drayton, 1613

In 1960, Dennis Potter, a writer and broadcaster whose upbringing in the Forest of Dean inspired much of his work, described his homeland as a “fortress” rising up dramatically between the rivers Severn and Wye, with England to the east and Wales to the west. Potter identified something in the land of his birth that has existed throughout its history: the sense of a small green world hemmed in by two rivers and two nations. Not quite either, not quite both; the locals simply being “Foresters” first and foremost. There is nowhere quite like it, and it is one of those rare corners of Britain where you can still glimpse the ways of the past; not encased in a museum, or ‘re-enacted’ in costume, but instead living on as a feature in an ever-changing landscape. There is no better example of this than the Freeminers: an ancient community who have been winning their livelihoods from the mineral wealth of the Forest for centuries.

Some might know the Forest as a popular filming location, with many productions gratefully borrowing its sense of the magical and primordial. Visiting its most picturesque spots, you might stumble across the backdrop to a lightsaber duel from Star Wars, a battle against the Weeping Angels from Doctor Who, a chase between Harry Potter and the Death Eaters, or a group of knights riding through the kingdom of Albion from Merlin. This beauty which draws visitors and storytellers from across Britain (and beyond) is inextricably linked to the great geological inheritance of the area. The mineral treasures of the earth have enriched the beautiful ecosystem above, and allowed generations of stewardship to transform the Forest into the place it is today. The story of the Freeminers is a vital seam running through this history, and is essential to understanding the unique cultural heritage and identity of the area.

The Origins of Forest Mining

In 1929, the author J.R.R. Tolkien visited Lydney Park, in the south of the Forest, to assist the archaeologists Sir Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler during the excavation of a Romano-British temple. The site, known by the Anglo-Saxons as Dwarf’s Hill, is thought to have been a shrine dedicated to the healing god Nodens. Tolkien characteristically took an interest in the linguistic provenance of the god’s name and contributed an appendix on the subject to the excavation report. Later, it was said that his visits to the area partially inspired his descriptions of Fangorn Forest in The Lord of the Rings. The Wheelers, meanwhile, uncovered more than a temple; finding tunnels and other signs of iron ore mining both during and far, far before the arrival of the legions in Britain. In sites like these, we can see ample evidence of the Forest’s resources such as coal and iron being extracted and sent outwards at scale. Multiple centuries (and multiple conquests) later, the area would remain important for its mineral resources, and a unique status would begin to develop for those hardy and skilled enough to spend their lives working below the earth of the Forest.

‘The King’s Pyoneers’

During the reign of Edward I, the administrative centre of the Forest was the castle in the village of St. Briavels. What is today a youth hostel was once a centre of production for arrows and crossbow bolts, where the wood of the Forest was fused in a deadly combination with the iron below its surface. Prior to one of his campaigns, Edward ordered no fewer than two hundred-thousand bolts to be made inside the castle. The King would also make excellent use of the very miners who had made such vast levels of production possible. Becoming known as ‘The King’s Pyoneers,’ Foresters were set to work undermining (literally mining under) enemy structures and fortifications in order to cause a strategic collapse. The story goes that the Pyoneers were so successful at this during a siege and capture of Berwick-upon-Tweed that the King rewarded them handsomely: they became ‘Free Miners,’ respected enough for their hard-won expertise that they could choose where to mine within the boundaries of the King’s Forest. These chosen sites are known as gales; grants of land acquired through a grant from the Crown. Forest Law, a system of governance for Royal Forests introduced during the reign of William the Conqueror, was amended in order to accommodate this elevation in status. A physical embodiment of this settlement can be found in ‘The Forester’s Horn,’ an ornate chimney atop St. Briavels Castle which projected like a beacon the authority of Forest Law.

Henry V, born in Monmouth on the borders of the Forest, would call upon its miners during his 1415 campaign in France. The Foresters served alongside their South-Welsh neighbours with their formidable longbows and, after victory at Agincourt, further honours and privileges are said to have been granted to them. The wider world beckoned again in 1577, when a group of Forest miners sailed with the explorer Martin Frobisher on an expedition for gold in the New World, as well as for the fabled Northwest Passage. In the end, the journey was neither successful nor noble, and the Passage remained elusive, but the excavating marks of Foresters can still be seen on Kodlunarn Island (known to the Inuit people as Qallunaaq). A popular anecdote goes that when the Spanish Armada set sail a decade later, they were given orders that, if they could not conquer and hold territory, they should burn down the Forest of Dean before sailing home. Such was its perceived importance for the mining of ore and construction of ships. Like many good stories, this version of events is probably untrue. However, it does reflect a truth: the miners and their forest home have played an outsized role in a great many historic events.

Strife, Industry, and De-Industry

From the eighteenth century through to the twentieth, the Freeminers would face a rapidly and relentlessly changing world. By 1777, the settlement that Edward I had established for his Pyoneers was coming under significant strain. The Speech House, a grand hunting lodge today known as ‘the Heart of the Forest’, had for decades served as The Court of the Speech, where local authority over forestry, mining, and game was held. In culture as in law, it was the beating heart of the relationship between the Foresters and their home. But when two local officials broke into a chest containing the records of the Mine Law Court, in an escalation of a dispute they had with the Freeminers, it grievously damaged the Court’s ability to function. The absence of such records was keenly felt during the increasingly common attempts to divide and enclose parts of the Forest for the economic benefit of outside interests. To the Freeminers, and other Foresters, any activity that would limit their access to their birthright was a threat to their way of life. Things came to a head in 1831 when Foresters, led by the Freeminer Warren James, took action and tore down sixty miles of enclosure fences. Resolution came in 1838 with the Dean Forest Mines Act, which confirmed the ancient rights of Freeminers in law and which remains in effect today. It states that any man born within the old ‘Hundred’ – a division within a Shire – of St. Briavels, who is above the age of twenty one, and has worked for ‘a year and a day’ in a mine, is able to become a Freeminer. This was successfully expanded in 2010 to include women, but is otherwise unchanged.

Even as the industrial era utterly transformed the landscape of Britain, thanks to the Dean Forest Mines Act, the Freeminers were able to exercise some degree of autonomy: outside interests could begin to mine on a large scale, but only if a Freeminer had sold them the right to their gale first. Expertise was invaluable in the difficult and dangerous business of mining, and many Freeminers were drawn to jobs in deep mines and the largest Forest collieries. The cultural legacy of this industrial heritage, as in so many other places in the United Kingdom, is incredibly potent to this day. So too is that of the two World Wars, in which the skills of Foresters were called upon again in service of their country: in the Great War, the 13th Gloucestershire Regiment, known as ‘The Forest of Dean Pioneers’, found a role constructing and repairing infrastructure such as trenches and encampments. Just as in many regions shaped by industry, a strong community identity arose during this period. In the Forest, this identity fused together with the more individual spirit represented by Freemining. This synthesis of collectivity and individuality impacted law once again in 1946, when the sweeping Coal Industry Nationalisation Act of Attlee’s post-war Labour government made special exemptions for the Forest of Dean. However, as de-industrialisation began to bite, the Forest collieries were not spared. The last of the deep mines was closed in 1965, and the Freeminers found themselves returning to their gales, again in a minority below the earth, albeit joined by a number of laid-off men who registered as Freeminers following the closures.

Facing the Future, Honouring the Past

The legacy of Freemining is kept alive by those still practicing it in their gales, as well as those Foresters who wish to preserve it through public awareness. Traditional governance roles are now filled by Forestry England (previously the Forestry Commission) officials, and those interested can still undertake a ‘year and a day’ working below ground. There has been no hospital with a maternity unit within the Forest since the 1980s, raising concerns about the number of children born outside the old Hundred of St. Briavels. Where would new Freeminers come from? A new Community Hospital was opened in 2024, home to a midwifery team which supports the Forest’s higher than national-average rate of home births. The Forest is also home to an active and passionate local history society, as well as many interested locals proud to call it their home. Myself and other keen readers owe much to renowned historians of the Forest like Cyril Hart OBE. Hart is now remembered in the form of an arboretum named in his honour, which I recommend to any visitors. Sites such as Hopewell Colliery, Clearwell Caves, and the Dean Heritage Centre also provide a vital link with the history I have relayed.

From 2017 to 2022, a National Lottery Heritage Fund project named ‘Foresters’ Forest’ took place. This was a partnership between organisations, community groups, and individuals to highlight the built, natural, and cultural heritage of the Forest of Dean. The work undertaken attempted to spread awareness of just how special the Forest is, including the introduction of ‘green plaques’ with information about notable Foresters and the restoration of industrial buildings which would otherwise continue to vanish into the landscape. LiDAR technology, an aerial mapping system which uses downward-projected beams of light to produce a model of a geographical area, was used to identify around one thousand seven hundred sites of archaeological or historical interest; the memory of which could still be reclaimed. The sheer volume of history which has passed through the trees over the centuries is hard to process, and the role that Freeminers have played in this long Forest story is likewise hard to quantify. Even if the practice of Freemining is destined to someday end, the marks it has left on the Forest, on Britain, and on the wider world – literally and figuratively – will remain as testament. With so much local passion and goodwill surrounding their identity and legacy, and despite the fact that none of us can predict what fate might yet throw at them, I don’t think we should write them off just yet!

Written by Joseph Lowen-Grey

Bibliography

Figures

Figure 1. The ‘Freeminer Brass’ at All Saints Church, Newland (known as the ‘Cathedral of the Forest’). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Freeminer.jpg.

Figure 2. The View from New Fancy, the former spoil heap of a colliery, now a viewpoint and picnic area. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Forest_of_Dean_from_New_Fancy_View_(0090).jpg.

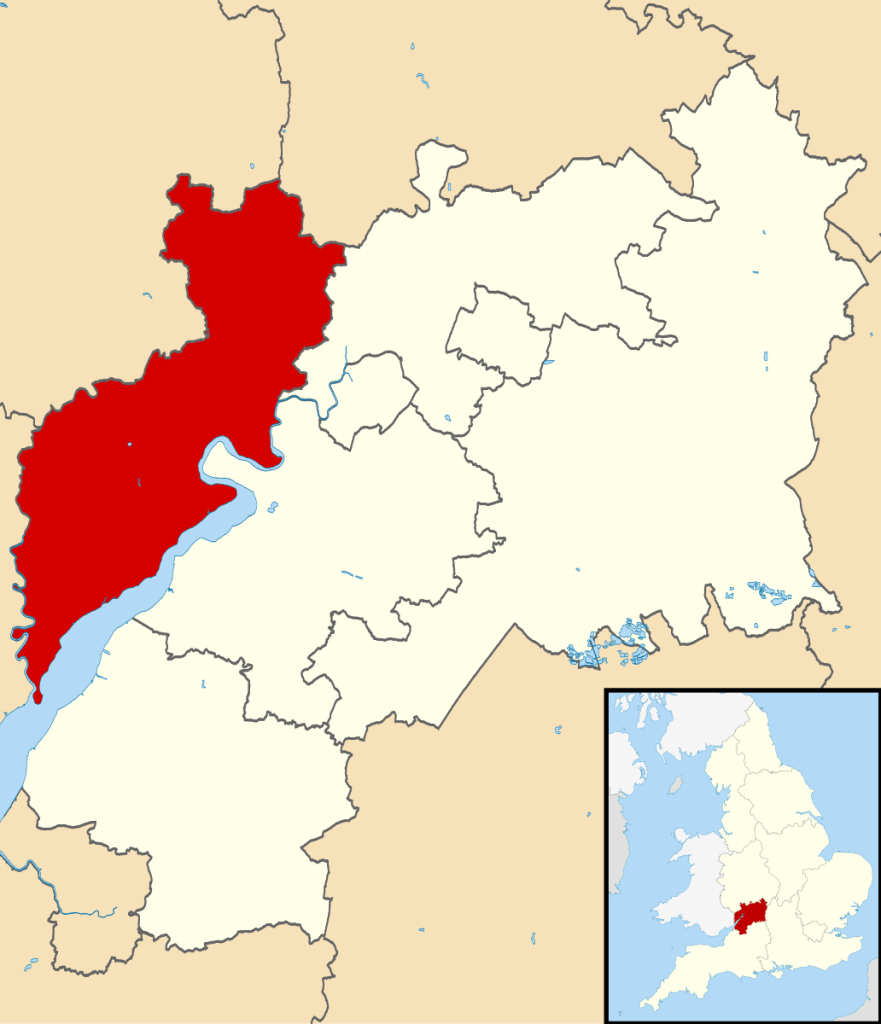

Figure 3. Forest of Dean District Map, within the County of Gloucestershire. Shared via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Forest_of_Dean_UK_locator_map.svg.

Figure 4. An 1823 depiction of St. Briavels Castle. Shared via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Briavels_Castle_Victorian_print.JPG.

Figure 5. The ‘Forester’s Horn’ chimney atop St. Briavels Castle. Shared via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Briavels_Castle_Forest_Horn_Chimney.JPG.

Figure 6. The Speech House, known as the ‘Heart of the Forest’. Shared via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Speech_House_in_the_heart_of_the_Forest_of_Dean_-_geograph.org.uk_-_3039789.jpg.

Primary Sources

“1960: CHANGING TIMES in the FOREST of DEAN | Between Two Rivers | Classic Documentary | BBC Archive.” BBC Archive. YouTube video. Posted by “BBC Archive,” April 6, 2025, accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HrBLexTsmoE&t=2s.

“Deep Roots, Dark Earth: Freemining in the Forest of Dean.” Forestry England. YouTube video. Posted by “Forestry England,” 27 Feb, 2025, accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoaO-ls1fqI.

“Freemining in the Forest of Dean.” Forest of Dean & Wye Valley. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.visitdeanwye.co.uk/blog/freemining-in-the-forest-of-dean/.

“Freemining in the Forest of Dean.” Hopewell Colliery Museum and Working Mine. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.hopewellcolliery.com/freemining.html.

Morris, Steven. “Woman wins right to hold ‘Free Miner’ title.” The Guardian. October 6, 2010, accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/oct/06/woman-free-miner.

“Revealing our Past.” Foresters’ Forest. Accessed May 5 2025. https://www.forestersforest.uk/themes/revealing-our-past.

“Royal Forest of Dean Freeminers Association.” Royal Forest of Dean Freeminers Association. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.forestfreeminers.org/history.html.

Secondary Sources

Bellows, John. “FOREST OF DEAN.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 13, (1899): 269-292.

Hart, Cyril. Between Severn (Sæfern) and Wye (Wæge) in the Year 1000: A Prelude to the Norman Forest of Dene in Glowecestscire and Herefordscire. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

Hart, Cyril. The Forest of Dean: New History 1550-1818. Stroud: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1995.

Hart, Cyril. The Free Miners of the Royal Forest of Dean and Hundred of St. Briavels. Gloucester: The British Publishing Company, 1953.

Hart, Cyril. The Verderers and Forest Laws of Dean. Lydney: Lightmoor Press, 2005.

Morris, Marc. A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. London: Hutchinson, 2008.

Nicholls, H.G. The Forest of Dean; An Historical and Descriptive Account, Derived from Personal Observation, and Other Sources, Public, Private, Legendary, and Local. London: John Murray Publishing, 1858.

Sandall, Simon. “Industry and Community in the Forest of Dean, c.1550-1832.” Family and Community History 16, no.2 (2014): 87-99. Straw, Michelle. “Forest Dialect: Discourses of Dialect, Place and Identity in the Forest of Dean.” English Today 143, Vol. 36, No. 3 ( 2020): 70-76.