PART I – A Brief Observational History of The Universe: Prehistory to the Middle Ages

INTRODUCTION

No matter where they lived, in any part of the world, our ancient hominid ancestors were fascinated by one common quintessence: the night sky. These celestial bodies of moons, planets, stars, nebulae, and galaxies would not yet be accurately identified for millions of years, and it is unknown what these ancient humans thought of when they observed those tiny, twinkling dots in the vast blackness of space.

In a series of articles entitled A Brief Observational History of The Universe, I will explore the developmental history of humanity’s celestial observations, focusing on the expansion of the universe, not in the physical sense, but rather our expanding knowledge of the human perspective. As our understanding grew and continues to grow today, so does the true scale of the universe. Part I begins with the earliest examples of astronomical observation and our ancient ancestors’ understanding of the cosmos.

PREHISTORY

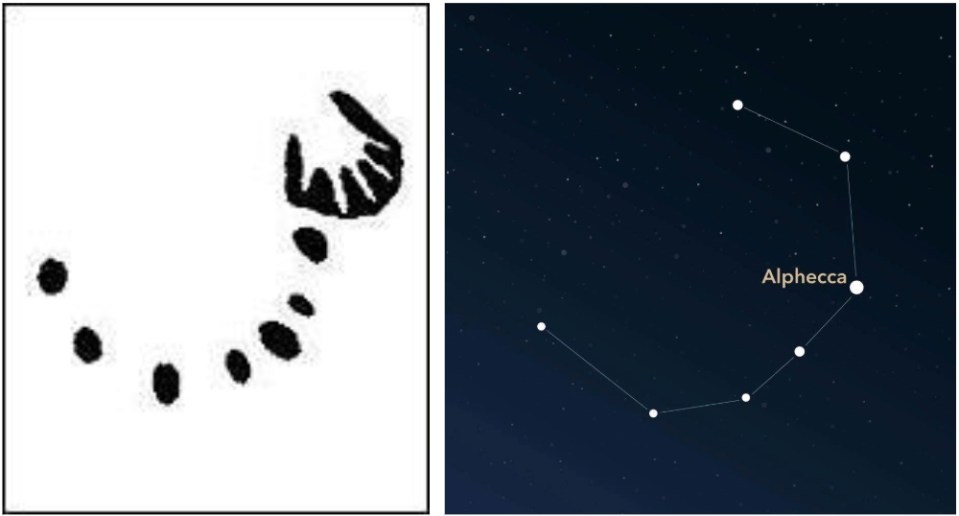

The night sky has intrigued and inspired early humans for thousands of years, as we can see in the artefacts they left behind. Prior to the invention of the written word in around 3400 BCE in Mesopotamia, early humans often recorded their astronomical observations through the medium of cave paintings. Below is a painting found at the mouth of the Cueva di El Castillo, a cave in modern-day Spain that holds a close resemblance to the modern constellation of the Northern Crown. Other cave paintings, most notably housed in the Lascaux caves in modern-day France, curiously feature constellations that are no longer visible in the same area and season. If a person were to stand at the mouth of the cave and look towards the heavens today, they would see a very different night sky to what is painted on the walls. This suggests that constellations’ positions in the night sky can change as time goes on, with some constellations disappearing below the horizon while others emerge. These records therefore show us what the night sky looked like up to 17,000 years ago and how different they are to today’s skies.

Furthermore, this discovery suggests that the constellations we see in different parts of the world today will change in the future, shape-shifting as the stars move independently throughout the galaxy. Constellations that we hold dear such as Triangulum, Cygnus, and Pisces may look unrecognisable in a million years. The constellation ‘Ursa Major,’ for instance, may no longer resemble the ‘great bear’ of today and may result in a renaming to something more recognisable to future humans. Conversely, perhaps other archaic humans such as Homo erectus and Neanderthals saw the stars in entirely different positions in the sky and so recognised constellations in ways which we can never witness.

ANTIQUITY

Civilisations prior to the era of scientific investigation relied on logic and mythology to explain the night sky. In all cultures, early humans most likely believed in the celestial sphere: an enormous dome that the earth was theoretically positioned inside, with the stars, sun, and moon situated on the underside of the dome. From the human’s perspective, all the stars appeared to be the same size and distance away, but some were brighter and others moved across the sky, being dubbed “wanderer” stars or “planetes.” As humans observed this celestial sphere, the brightest stars in the night sky garnered their attention and people began to connect the stars to form patterns and images through pareidolia (the phenomenon of perceiving patterns where none are intended), which we now call constellations.

The most recognisable constellation in the modern northern hemisphere is Orion the Hunter, named after Orion in Greek mythology. The three stars, Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka, are positioned closely in a straight line to make up Orion’s belt and draw the eye amidst the blackness of space. Because of this, many of the stars in Orion also appear in various other non-Greek constellations, such as the Belarusian ‘Throne of Jesus’ and the Inuit ‘Two Placed Far Apart’ and ‘Runners.’

Each culture has its own explanations for the images they see in the night sky, and most link directly to their religious, cultural, or mythological disposition. For example, ‘The Plough’ is an asterism originating in England, but its seven stars also make up the tail-end of Ursa Major. The English know it as ‘The Plough’ because they associate it with the farming implement commonly used around the country, whilst in other parts of the world, the same asterism is called ‘The Big Dipper,’ as it more resembles a ladle. So too is there great diversity in the understanding of the collection of stars that we know as the Milky Way, our galaxy.

Hera as she ripped the baby Heracles away from her breast after mistakenly nursing him. Alternatively, the Kaurna people of South Australia believed it to be the river Wodliparri in the sky world, with surrounding stars as campfires along the riverside. The Cherokee people thought the galaxy, which they called ᎩᎵ ᎤᎵᏒᏍᏓᏅᏱ (pronounced Gili Ulisvsdanvyi), to be spilt cornmeal, cascaded by a thieving dog, while the Ancient Egyptians may have believed the Milky Way as a celestial manifestation of Nut, the sky goddess. Estonian folklore dictates that the galaxy guides native birds to migrate to “bird home” in the winter (which was later discovered to be scientifically accurate, as birds moved south to avoid the cold). Finally, the Maori believed the galaxy to be a canoe and the stars shiny pebbles, cast out to deter the Taniwha from attacking people in the dark of night.

While mythology was the main source of explanation for the lights in the heavens at this time, it does not mean that humans were incapable of scientific investigation. Continuing on from the logic-based stories used to interpret the universe, the geocentric model was adopted by most, if not all, civilisations during antiquity. Astronomers such as Ptolomy, seeing that the Sun moved across the sky, assumed that the Earth was at the centre of the solar system, with the sun, moon, stars, and planets revolving around a stationary Earth. Observations such as Mars’ apparent retrograde motion could be explained simply by applying an epicycle, meaning that humans believed the planets to not only orbit the Earth, but also orbited a point in space close to them. This would explain why planets appear to perform a loop-de-loop as they travel through space. The geocentric model would not be superseded until the Renaissance period, when it was discovered that it was merely a combination of the Earth’s perspective and its own orbit which made it appear that Mars had a retrograde motion. More on this can be read in Part II.

MIDDLE AGES

As we move out of antiquity, we enter the early Middle Ages, where the recording of astronomical observations became more commonplace globally: in particular, for supernovae and comets. Supernova 1054 (SN 1054), the great death and explosion of a star that would later create the Crab Nebula, is proposed to have been recorded on rocks in the Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, in 1054, along with various other astronomical accounts. For humans on Earth, the supernova looked like an incredibly bright star that shone during the day and night time. The pictograph below shows the proximity of SN 1054 to a waxing crescent moon, suggesting the time of month that this explosion was sighted. SN 1054 was also recorded in writing and oral tradition by various other civilisations, such as in Japan, Iraq, Australia, Byzantine (in which the supernova may have been recorded on coins issued in that year), and China, the latter having recorded it as a ‘guest star’ that remained in the sky for two years.

In the eighteenth century, Charles Messier would mistake the Crab Nebula for our next topic of investigation, Halley’s Comet. This comet is an ice body caught in an extreme gravitational pull of the sun, which forces it to orbit the sun all the way out to Pluto in just 76 Earth years in a tight elliptical fashion (for context, Pluto orbits the Sun in a spherical fashion and takes 248 Earth years). It had been observed as early as 240 BCE by Chinese astronomers in the chronicle Records of the Grand Historian. Not yet understanding that the comet was a returning visitor every 75-76 years, Babylonian scribes also recorded it as separate events in 164 BCE and 87 BCE. It would not be until 1758 that astronomers worked out that this comet was a returning visitor, after Edmond Halley predicted its return in the same year. The comet continued to be consistently observed all over the world as it came and went, until 1066, when it was observed in both England and Normandy just before the Battle of Hastings. It is recorded in written form in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and recorded visually in the Bayeux Tapestry.

“Then was all over England such a token seen as no man ever saw before. Some men said that it was the comet-star, which others denominate the long hair’d star. It appeared first on the eve called Litania Major, that is, on the 8th before the calendar of May; and so shone all the week.”

– The Saxon Chronicle

While Harold Godwinson and the English army believed the comet to be a bad omen, as was the lore of the period, William the Conqueror and the Norman army took it as a sign of support from God. It is unclear whether these beliefs originated in retrospect as a form of propaganda through divine signage for the Normans (i.e perhaps William justified his legitimacy by citing the heavenly bodies) or whether the two armies did truly believe that the comet told them the future of their fight. It is also possible that their superstitions upon seeing the comet worked as a ‘jinx,’ meaning that their belief came true after apparent heavenly endorsement.

Similarly, in the late Middle Ages, a parhelion appeared on the morning of the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross in England, 1461, during the Wars of the Roses. A parhelion is an atmospheric optical phenomenon which causes two bright spots to appear either side of the sun within a halo. Much like with Halley’s Comet, the Yorkist army considered it to be a bad omen, but Edward of York (soon to be called Edward IV) convinced his soldiers that it was a sign that God was on his side and that the three suns represented the Holy Trinity. After winning the battle, Edward made the parhelion his emblem.

William Shakespeare recounts this event in his play Henry VI, Part III. It is unclear if the parhelion was also seen by Lancastrian forces and, if so, whether they took it to be a positive or negative sign. Once again, it also calls into question whether believing that celestial events to be a good or bad sign has a direct effect on the outcomes of battles, wherein believing it to be an omen results in soldiers despairing, and believing it to be a sign from God results in soldiers fighting with renewed vigour.

CONCLUSION

Here we leave the astronomical observations of prehistory, antiquity, and the Middle Ages. In my next article, we will move into the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, where scientific discovery began to replace mythological belief and folklore. We will investigate how scientific observation and religion clashed in Europe as humankind begins to fully grasp what truly resides in the night sky, and beyond.

Written by Annon Ford. Special thanks to Elizabeth Leon

References

Barnett, Amanda. “Chapter 2: Reference Systems.” Basics of Spaceflight. Jan 16, 2025. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://science.nasa.gov/learn/basics-of-space-flight/chapter2-2/.

BBC News. “Ice Age star map discovered.” Online article. Aug 9, 2000. Accessed Mar 20, 2025. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/871930.stm.

Cox, Brian. “An Unexpected History of Science.” BBC Radio 4: The Infinite Monkey Cage, podcast audio, Aug 14, 2024. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p0j98c02.

Cox, Brian. “Starless World.” BBC Radio 4: The Infinite Monkey Cage, podcast audio, Nov 27, 2024. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0025d6q.

Cox, Brian. “Under our Night Sky.” BBC Radio 4: The Infinite Monkey Cage, podcast audio, Jan 18, 2021. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000rd1c.

D. Filipović, Miroslav et al. “European historical evidence of the supernova of AD 1054 coins of Constantine IX and SN 1054.” European Journal of Science and Theology 18, no.4 (2022): 51-66.

Fellows, Paul. “How big is the universe?” Lecture for the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, University of Leeds, Leeds, Mar 24, 2025.

Graur, Or. “The Myths and Lore of the Milky Way.” The MIT Reader Press. Aug 1, 2024. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-myths-and-lore-of-the-milky-way/.

Rao, Joe. “Doorstep Astronomy: See the Big Dipper.” Space.com. May 9, 2008. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.space.com/5323-doorstep-astronomy-big-dipper.html.

Royal Bastards: Rise of the Tudors. “Episode #1.1.” Sky HISTORY. Nov 26, 2021. Television Broadcast.

Sagan, Carl. Cosmos. London: Macdonald Futura Publishers, 1981.

Various. The Saxon Chronicle. Translated by James Ingram. London: Longman, 1823.

V. Schroeder, Daniel. “Understanding Astronomy: Astronomy Before Copernicus.” 2011. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://physics.weber.edu/schroeder/ua/BeforeCopernicus.html.

“When Was Writing Invented?” Thesaurus.com. Dec 4, 2020. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.thesaurus.com/e/writing/when-was-writing-invented/.

Whistler, Simon. “Halley’s Comet: Earth’s Constant Companion.” YouTube video. Posted by “Geographics.” June 7, 2021. Accessed Mar 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gmvdnpnt50A.

Wonders of the Solar System. “Order Out of Chaos.” BBC Two. Mar 14, 2010. Television Broadcast.

Wonders of the Universe. “Falling.” BBC Two. Mar 20, 2011. Television Broadcast.

Image References (In order of appearance)

BBC News. “Ice Age star map discovered.” Illustrative copy. 2000. Accessed Mar 20th, 2025. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/871930.stm.

Star Registration. “The constellation Corona Borealis”. Image. Posted by Marc Mayr. Apr 16 2023. Accessed 24th March, 2025. https://www.star-registration.co.uk/blogs/constellations-and-zodiac-signs/constellation-coron a-borealis.

Pogge, Richard P. UMa Proper Motions Gaia DR3. 2025. Animated GIF, 854 x 480 px. Accessed Mar 25, 2025.

ChristianReady. “Celestial Sphere.” 3D Render. Wikimedia Commons, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Celestial_Sphere_-_Eq_w_Label_figures.png.

Chéreau, Fabien. Stellarium. Version. 24.4 (Toulouse: Stellarium Labs, 2024). Computer software.

Ciszewski, T. “Milky way over lassen national park.” Photograph. Unsplash. 2018.

Alvin Villar, Eugene. “Apparent retrograde motion of Mars in 2003.” Animation. Wikimedia Commons, 2008.

V. Schroeder, Daniel. “Epicycle.” Digital Illustration. Understanding Astronomy: Astronomy Before Copernicus, 2011. https://physics.weber.edu/schroeder/ua/BeforeCopernicus.html.

Marentes, Alex. “Anasazi Supernova Petrographs.” Photograph. Wikimedia Commons, 2006.

DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, ENSICAEN, “The Bayeux Tapestry.” Photograph. Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Bayeux, 2017.

Gopherboy6956. “Fargo Sundogs 2 18 09.” Photograph. Wikimedia Commons, 2009.

“Typological life and genealogy of Edward IV.” Illumination. British Library Images Online, 1460. Courtesy British Library, Harley 7353.