The King’s Contemptuous Subjects: The Bristol Revolt of 1312-1316

Introduction: England in the Fourteenth Century

The fourteenth century in England was a time of great dysfunction and tumult. The kingdom experienced one of its most devastating famines between 1315 and 1322, the Black Death in the late 1340s, and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Yet before all of this came one of the most significant but understudied urban rebellions of medieval England, lasting four years in Bristol from 1312 until 1316.

England in the early 1310s saw no respite from the chaos of this century, suffering political turmoil in the form of conflict between Edward II, in support of his close companion, or lover, Piers Gaveston, and the lords of the realm. Throughout the decade, Edward II would fight a political game against his nobles for control of the governance of England. Amidst all this, England was saddled with the legacy of Edward I’s wars in Scotland, culminating in the disaster at Bannockburn in 1314. The circumstances were ripe for order and political authority in the kingdom to break down.

The Great Urban Centre of the West

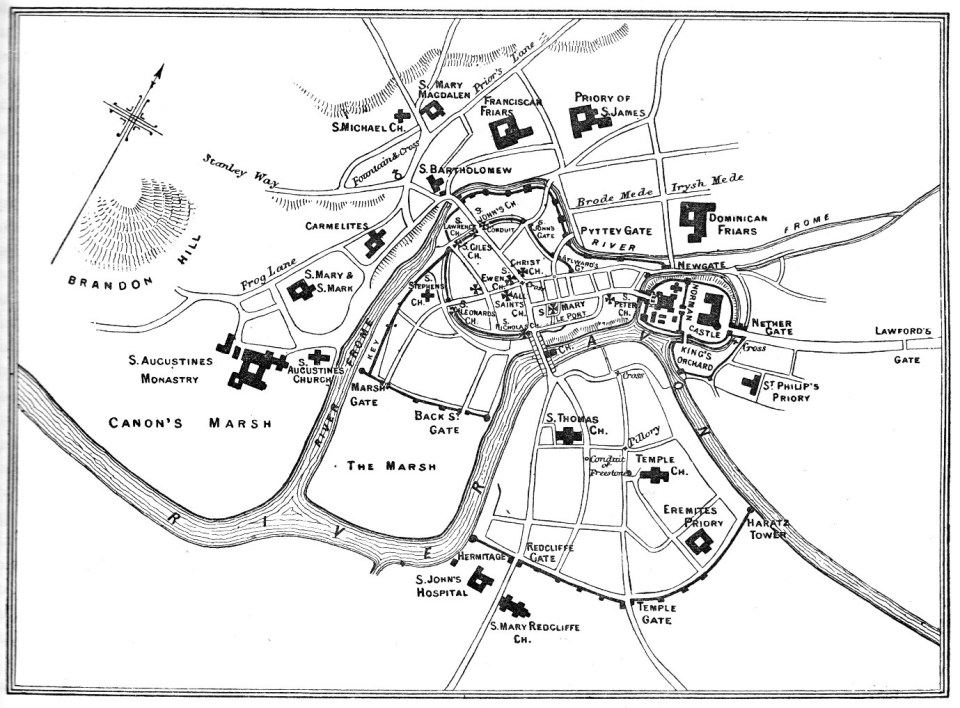

Bristol was one of the chief towns of medieval England: it did not have the antiquity of London or York, but served as a key port for continental trade, particularly with the English territory of Gascony. A dynamic and vibrant town, Bristol had seen rapid growth in the preceding centuries, reflected in it having two complete circuits of walls to enclose its suburbs, and had become the largest settlement in the kingdom without city status.

Towns such as Bristol held urban autonomy with an intricate system of civic government. A limited portion of the adult male population of each town held citizenship, which gave them economic privileges, particularly the right to trade without paying tolls and, crucially, the privilege of participation in civic government. The key official within the town was the mayor, selected annually by and from the most elite citizens. Despite their urban liberties, the Bristolians still had to know their place within English society: the town was the property of the King, and each year the Mayor had to swear his oath of office at the gate of the king’s castle to the constable.

Our Sources

Thankfully, there is a wealth of government records from the fourteenth century which has survived, even if there is so much more that we as historians wish we could have available to us. Most significant amongst these sources are the patent/close rolls, two series of letters issued by the king’s government dealing with a range of important matters. We are also very fortunate that a section of the parliament rolls concerning the Bristol rebellion has survived: Edward II’s reign has otherwise left a very fragmentary collection of parliament rolls. We must remember, however, that all of these sources provide a royal perspective in which the Bristolians are portrayed as contemptuous of their royal lord. Finally, we also have a limited narrative account from the Vita Edwardi Secundi, a chronicle source which takes a firmly royal stance.

The Outbreak of Violence

The dispute emerged early in 1312 with Edward II’s efforts to launch a new campaign in Scotland. The royal government, through the constable Bartholomew de Badlesmere, aimed to levy troops and taxes on the town. This created a divide between the bulk of the citizens who opposed such a measure and what Samuel Cohn describes as the “elite fourteen” – a group of Bristol’s leading citizens who tried to enforce Badlesmere’s demands. We must remember, though, that this was not a simple Marxian class conflict: the man who would come to take leadership of the rebel faction, John le Taverner, was himself an elite figure as a former Mayor and Member of Parliament for the town, and the ordinary citizens were an advantaged minority within the town too. Rather, this developed into a conflict in defence of Bristol’s liberties, an essential part of their privileged urban identity.

Events quickly turned violent in the town with John Bel, a townsman, being killed by members of the garrison of Bristol Castle from its walls. Genuine investigations seem to have been carried out into this at first, but, in September 1312, the royal government suddenly performed a U-turn. They released the garrison members from prison on the grounds that it could not be proved who fired the fatal shot and demanded the town’s submission to Badlesmere, reigniting the conflict.

At this point, the key rebel leader John le Taverner was elected to the Mayorship. The city under Taverner’s leadership refused to acknowledge their subordination to Badlesmere: instead of presenting himself to the Constable to swear his oath, Taverner was presented directly to the King. At the same time, revenge was exacted on the “elite fourteen.” The Patent Rolls state in January 1313 that Taverner had removed their liberty, stripping them of their civic privileges: a seriously debilitating move for their economic and political power. Violent attacks were recorded, with the leader of the elite fourteen, William Randolf, complaining in December 1313 that he had been forcibly prevented from living or trading in the town, his property had been broken into and goods stolen, and his servants had been assaulted and imprisoned. Randolf directly accused Taverner of being an instigator of this violence. These attacks were clearly premeditated, with a further twenty-two perpetrators individually named, along “with others of the town.” The patent rolls describe an impressive series of fortifications thrown up against the castle, with a stone wall built over the street opposite the castle, into which arrows were fired, alongside barricades constructed in “diverse places in the town.” The patent rolls suggest that these fortifications were financed through the levying and appropriation of taxes in the town.

Restoring Order

What was to be done against such a degradation of order? The royal government tried several times in 1313 to bring the rebels to heel, at no point succeeding. In January, a commission was sent to resolve the dispute and, in February, the leading figures of the town were summoned to Parliament to explain themselves. Renewed efforts were made in the Spring, with the Sheriffs of Gloucester, Somerset, and Dorset ordered to march on the town with the men of their counties. It was at this point that Taverner, amongst other burgesses, was apprehended and sent to the Tower of London, ending his tenure as Mayor.

Even this decisive action could not restore order as, in June 1313, tax commissioners were refused entry into the town on account of the imprisonment of the burgesses in the Tower. A commission was sent in the same month to investigate the previous disturbances and resolve the dispute with the elite fourteen. At this point, the Vita Edwardi Secundi joins the story. The chronicle recounts how a jury had been brought in from outside the town, which was believed to have been biased towards the elite fourteen. The author invents the following speech from the civic leadership to the townspeople:

“Judges favourable to our opponents have come, and to our prejudice they admit outsiders, by which our rights will be lost for ever.”

The situation instantly devolved into a riot as eighteen people inside the court were killed. The Vita claims that people tried to escape through upper-story windows and the judges were only just spirited away to safety. Eighty men were indicted but, protected within the town, never saw justice.

This violence demonstrated the core of the ideology which the revolt was based around: a defence of urban liberty against outsiders. As an incorporated town, Bristol was supposed to have an exclusive right to try its citizens, and so they could not appeal to outside courts. By bringing in external justices and juries, the government had severely offended popular opinion, leading to this existential struggle to defend their liberties encapsulated so well by the Vita’s imagined speech.

Negotiation

Following these failures, Taverner and the other burgesses were released from the Tower, presumably in an attempt at reconciliation. In the years 1314 and 1315, the rebellion in Bristol is mentioned less frequently. Following the King’s defeat at Bannockburn in June 1314, he was forced to surrender government power to his cousin and great rival, Thomas of Lancaster, who would effectively rule England for the next four years. In August 1314, direct orders were given to Badlesmere and the Earl of Hereford and Gloucester to not besiege the town. The Vita, however, claims that he had conducted an unsuccessful siege: clearly there were disagreements amongst the leading nobles over how to respond.

By 1315, Lancaster had a novel solution to the troubles at Bristol, organising a conference at Warwick on Sunday 8 June. The government delegation was led by the Earl of Warwick and the Lord Chancellor, who met with unnamed delegates from Bristol, though we know that the most significant rebels could not have attended as outlawed individuals were not allowed safe-conduct. According to the patent rolls, an agreement was reached but the details were sadly not recorded, though a later patent roll entry suggests compensation to Badlesmere was part of the deal.

The conference was a surprising and significant event, perhaps even representing the zenith of the Bristolians’ power. The fact that a leading noble and one of the main crown ministers were forced to negotiate with urban freemen as if they were equals shows a government which had completely lost control of the cards.

Taverner’s Last Stand

The agreement made at Warwick did not last. By June 1316, the government had had enough of what the Vita termed the Bristolians’ “wickedness.” The Sheriff of Gloucester was once again sent to the town with orders to apprehend Taverner and bring him to trial on charges of murder. When Taverner was found in the Guildhall, the seat of civic government, the citizens of Bristol prevented his arrest. In a sign of the extraordinary ingenuity and organisational skill of the rebels, fortifications were re-erected, more advanced than before. When the Sheriff returned with the forces he could levy in Gloucestershire, he was faced with a 7-metre wide ditch, wooden forts, towers, and siege engines which had been built facing the castle.

By now, the point of no return had been reached. Royal orders were given that any communication with the town was forbidden, a sea blockade was imposed, and a new army under the command of the Earl of Pembroke besieged the town. Bristol held out for several days before the damage caused by the castle’s siege engines to the makeshift fortifications and the town’s buildings caused them to surrender on 9 August.

By this point, Taverner had sought sanctuary in a church in the town, obviously fearing for his life. Remarkably for such an obstinate rebellion, the sanctions were light. No one was executed and the town was merely fined 2,000 marks in return for a general pardon in December 1316. Taverner too would eventually be pardoned, but he would have to wait until 1321.

Conclusion

The Bristol Rebellion was an extraordinary example of late medieval urban protest in its duration, violence, persistence, and success. For four years the town held out against repeated attempts to bring it to heel and even managed to secure high-level negotiations with the royal government. More than anything, it shows the lengths that an urban community would go to in defence of its liberties and perceived slights against those liberties, as Bristol doggedly refused to accept the judicial arbitration of outsiders, forcibly expelling those who tried.

Written by Daniel Cramphorn

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Calendar of the Close Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Edward II. A.D. 1307-1313. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1892.

Calendar of the Close Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Edward II. A.D. 1313-1318. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1893.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Edward II. A.D. 1307-1313. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1894.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Edward II. A.D. 1313-1317. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1898.

Given-Wilson, C., Brand, P., Curry, A., Horrox, R.E., Martin, G., Ormrod, W.M., and Phillips, J.R.S., eds. Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, http://www.sd-editions.com/PROME/home.html.

Vita Edwardi Secundi. Translated by Wendy R. Childs. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005.

Secondary Literature

Cohn, Samuel K. Jr. Popular Protest in Late Medieval English Towns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Cohn, Samuel K. Jr. “Revolts of the Late Middle Ages and the Peculiarities of the English.” In Survival and Discord in Medieval Society: Essays in honour of Christopher Dyer, edited by Richard Goddard, John Langdon and Miriam Müller, 269-285. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2010.

Liddy, Christian D. Contesting the City: The Politics of Citizenship in English Towns, 1250-1530. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Maddicott, J.R. Thomas of Lancaster, 1307-1322: A Study in the Reign of Edward II. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Phillips, J.R.S. Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, 1307-1324: Baronial Politics in the Reign of Edward II.Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.

Swanson, Heather. Medieval British Towns. Basingstoke: MacMillan Press, 1999.

Images

“An illuminated detail from BL Royal MS 20 A ii, Chronicle of England [folio 10], showing Edward II of England receiving his crown.” Wikimedia Commons.

Nicholls, J.F., and Taylor, John. “Map of Bristol in the 13th Century.” Wikimedia Commons.

Nicholls, J.F., and Taylor, John. “Water Gate to Bristol Castle.” Wikimedia Commons.

Ricart, Robert. “Robert Ricart’s Map of Bristol.” Wikimedia Commons.