Perpignan or Perpinyà? Exploring the Multicultural History of the Southwest French City

Introduction

Perpignan, situated 13 kilometres west of the Mediterranean Coast in the south of France, is the last large city closest to the Franco-Spanish border. Before the establishment of a fixed border, Perpignan changed hands many times between the Crown of Aragon and the French Republic. The border was only formally defined when the northern parts of Catalonia were finally ceded to France in 1659 in the Treaty of the Pyrénées, and have been under French control ever since. Whether under Spanish or French governance, being the first entry point into France/Spain respectively, Perpignan was treated as a defence city to be constantly maintained and fortified in case of invasion. Much like its history, Perpignan as it stands today remains ensnared between French and Catalan culture. The administration of the French department of the Pyrénées-Orientales (also known as Northern Catalonia) is located in Perpignan, prompting the nicknames “the capital of North Catalonia” or “the heart of French Catalonia.” Evidently, the Catalan culture is deeply rooted in the history of Perpignan, but how “Catalan” is the Perpignan of today? This article analyses how the history of Perpignan has led to the current multicultural city and how these two cultures co-exist. How has the Catalan identity remained so strong? How does Perpignan reconcile its French, and Catalan identity/history? Can it be classified as a French or a Catalan city?

Origins/History of Perpignan

There are two legends regarding the founding of Perpignan or Perpinyà (in Catalan). The first is that following a massive fire that destroyed the Pyrénées in the late ninth century BC, the people who fled constructed their homes next to the river Tet in a place they called Pyrepinia (originating from the Greek and Phoenician which means “starting of a fire”). The second is the tale of a man named Pere Pinya who lived in a poor hamlet situated in the mountains of Tosa. Disgusted by the life he led, he decided to change country, flee to the edges of the Tet, and his house slowly became known as a city: Perpinyà. It is unclear whether the legends have any historical basis for the origin of Perpignan, but they do suggest there may have been ancient foundations to the city. However, the earliest mention of Perpignan is in a document dating back to 927 BC. In historiography it is classified as a medieval city, calling into question the credibility of the legends. From this date until 1172, Perpignan became the primary residence of the Counts of Roussillon, who ruled over the Catalan county of the same name. From 1172, the County of Roussillon was subsumed within the Crown of Aragon and called the Principality of Catalonia. Effectively, Perpignan was under both jurisdictions until 1276, when James the Conqueror (King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona) founded the Kingdom of Majorca which lasted until 1344. It was during this time that many key buildings, such as the Palace of the Kings of Majorca, the Hôtel de Ville, and the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist were established. From 1344 until 1463, Perpignan once again became part of the Principality of Catalonia. The city was attacked and occupied by Louis XI of France in 1463 but then restored to Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1493. It remained under Aragon control until 1659, when the northern parts of Catalonia were officially ceded back to France in the Treaty of the Pyrénées.

Although Perpignan has been under French control for the last 385 years, it is safe to say that the 732 years of Catalonian history cannot be ignored. Perpignan and the surrounding region remind us of the typical south of France: sun, beach, beautiful vineyards, rich art and history, and the sheer number of small local businesses/delicacies. Yet, Perpignan stands out slightly from other places in the south, as the Catalan culture can be seen in the languages spoken, education, heritage, architecture, gastronomy, politics, music, art, and much more. Though, upon a visit, the Catalan culture seems to shine in the Perpignan centre; its inclusion and maintenance not met without contestation. I will focus on three main multicultural aspects: linguistic, heritage, and gastronomy to indicate that the strong Catalan identity remains in Perpignan. What impact does the Catalan identity have on the locals and their perception of the city? If French and Catalan cultures can be cohesively intertwined, then how?

Multiculturalism

Linguistic Aspect

The linguistic situation in Perpignan is complex and unique. To adequately analyse this, it is important to summarise the origin of the Catalan language, how it differs from Castilian Spanish (spoken in most of Spain), and its status compared to French. The Catalan language first appeared in 1114, and became the national language during the Golden Age of Catalonia (1276-1344). From 1412, when Catalonia was under the Castilian Crown, Castillian began to rival Catalan and, in 1516, Catalan lost its status as the national language. Despite the efforts of the French government, the region resisted Frenchification for a long time. It was only with the introduction of free and compulsory teaching of French that it emerged as a rival language in 1880. Consequently, Catalan was no longer recognised in schools and was perceived as an inferior language, whereas French was taught as the language of culture and modernity. French Professor, Dawn Marley, argues that other factors further contributed to French gaining such traction in the nineteenth century. First, lack of employment forced young people to look elsewhere, mainly northern France where one had to speak French. Second, the French wars against Germany in 1870, 1914, and 1939 gave inhabitants a sense of belonging to France. Third, the railway line that was established in Perpignan in 1862 physically linked the region to the rest of France and isolated the city from the rest of Catalonia (in Spain). Clearly then, the decline of Catalan was not just a cultural matter but was exacerbated by a variety of economic, social, and political factors.

The repression of their language has had a directly detrimental effect on Catalans living in Perpignan. Marley argues that they feel mocked by both “real” French and “real” Catalan people; effectively, they occupy a liminal space in Perpignan and have no firm sense of belonging. In the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, pupils who spoke Catalan were punished so the language quickly became a symbol of shame. Those who were subject to these humiliations wanted to avoid the same fate for their children so they raised them to speak French. Since most Catalans now receive a French education, they are unaware of Catalonia’s rich history and literature, exacerbating their lack of belonging. Since World War Two, Catalan has ceased to be a mother tongue in Roussillon (part of the larger department Pyrénées-Orientales). In the late 1960s, Catalan was only spoken by older people, most of whom believed it to be “a backward patois.” With the rise of French media, Catalan is now mainly used for traditional folk activities, isolating it from everyday use and appreciation. Even the Catalanists (Catalan nationalists) realise that this inclusion of Catalan is not enough for its survival.

However, the language’s survival was not completely hopeless. The 1960s saw the emergence of activist groups like GREC (Grup Rossellonés d’Estudis Catalans) who made Catalan more visible in academic spheres, notably with the founding of the first Catalan University in 1969. Further activism was carried out in the 1970-1980s for the preservation of Catalan, with the first Catalan school, Bressola, opening in 1976, followed by the school Arrels in 1980. Today, bilingualism is evidenced in every street sign in Perpignan, written both in Catalan and French.

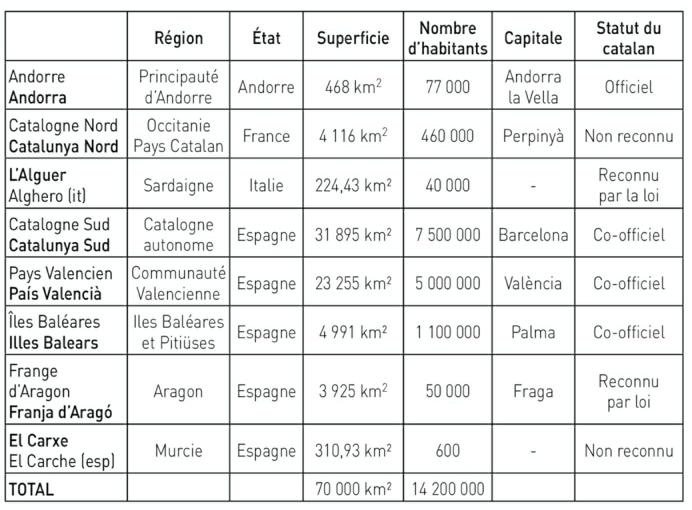

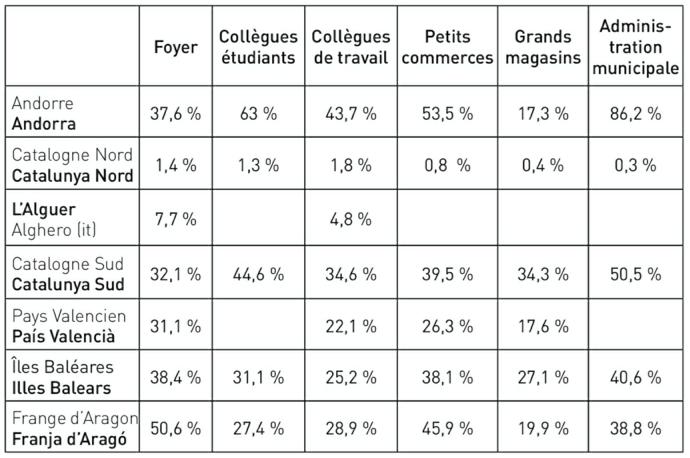

Despite these positive initiatives, ethnographic scholars have disagreed about the fate of Catalan. For instance, in her study, conducted by questionnaire in 1988 and again in 1993, Marley concluded that Catalan will never regain the space occupied by French. Contrastingly, in Le catalan en Catalogne Nord et dans les Pays Catalans: Même pas mort!, French linguist Alà Baylac-Ferrer argues that, though in a critical situation, Catalan in Northern Catalonia is not dead, rather, it is “an object of desire” and “a hope for the future.” Baylac-Ferrer’s findings (shown in the three figures included above) indicate the status of Catalan of 2015, its use, and its recognition. In all the tables, Northern Catalonia has the lowest percentages regarding the use and perception of Catalan compared to other Spanish countries, indicating the lack of effort in fostering Catalan regionally. Particularly shocking is the third table that displays the use of Catalan among young people; Catalan is very rarely spoken on its own and, if it is, it takes place amongst friends or with paternal grandparents. The table tells us that Catalan is not spoken at all with parents or children, indicating the intergenerational shame of transmitting Catalan. Additionally, the fact that Catalan occurs most commonly alongside other languages implies that it is not seen as a valuable language in its own right, and that its survival depends on its integration with French. Evidently, the integration of Catalan is difficult, and the language is in a fragile situation. I believe that, if it is to survive, it requires education and respect from those in leadership as well as the community.

Heritage Aspect

Much of the pre-seventeenth century heritage shows the richness of the Catalan culture and history. This is most apparent in one of the key symbols of Perpignan: Le Castillet. Meaning “small castle” (castille), it was divided into three sections: the tower was built from 1368, and the construction of the keep and the Notre Dame city gate were both completed in 1483. After the Treaty of the Pyrénées, Louis XIV converted it to a state prison and it remained so until the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, it held the municipal archives and, since 1963, it has housed the Casa Pairal museum (a Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions of Perpignan that displays objects used daily by Catalan people). This included work tools of master glassmakers from Palau, whip makers from Sorède, traditional Catalan outfits, and a reconstructed Catalan kitchen. Most importantly, it holds the Flama del Canigó (Canigou Flame), a ritual which is combined with the yearly Saint Joan Midsummer celebrations to evoke the common identity of Catalan-speaking lands. The ritual began in 1955 and crossed into France for the first time in 1966. The flame is kept burning throughout the year until the 22nd of June when it is carried to the summit of Mount Canigou (the Catalan’s sacred mountain). At midnight, the fire from the flame is shared with everyone present and, with this messenger, the fire is lit in the surrounding towns and villages. That this hugely symbolic festival for Catalan identity is now celebrated in Perpignan is already significant. However, the fact “the flame of the Catalan culture” is safely kept in one of Perpignan’s most iconic buildings indicates that the locals and the government have made an active effort to value Catalan culture. Classified as a historic monument in 1889, the Castillet is a palimpsestic building of historical importance, having been a defensive tower, a prison, a national archive, and now has transformed into a key symbol of Catalan identity and culture. I think the Castillet is a perfect example of a successful blend of French and Catalan Culture.

Gastronomic Aspect

The influence of Catalan culture is perhaps most evident in the Franco-Catalan cuisine of Perpignan. Savoury Catalan specialties include Boles de Picolat (meatballs with tomato and white beans), Escalivade (oven roasted tomato, peppers, onions, and aubergine), Ouillade (a Catalan stew), and Cargolade (snails prepared in a Catalan style). Desserts include Crème Catalane (a custard like cream with star anise and cinnamon), Coque Catalane (also known as fougasse– a brioche pastry fruit and pine nuts), and Rousquille (a round shortbread cake covered with powdered sugar, tasting of aniseed and lemon). Finally, Le bras de Venus (also known as “gypsy arm”), is a sponge cake rolled with crème pâtissière or chantilly inside, then topped with egg cream and caramelized. Although French and Catalan cuisine easily co-exist as they are both Mediterranean-based, the existence of many cafes and restaurants that offer only Catalan specialties indicates that there is a popular demand for these dishes from locals and tourists alike.

Conclusion – Perpignan, Perpinyà, or Both?

Although since 1659, Catalan culture has been suppressed and difficult to integrate in Perpignan, the late twentieth century has seen a significant change: transforming the culture into a source of pride, this has led to a colourful and rich city attracting many tourists every year. Declared the capital of Catalan Culture in 2008, Perpignan is no longer just a French city, and this strong bicultural identity is precisely what makes Perpignan unique. In 1963, the Catalan artist Salvador Dali declared Perpignan’s railway station the “El Centre del Mon” (Centre of the Universe) after having a vision of “cosmogonic ecstasy.” He illustrated his vision in his 1965 painting, La Gare de Perpignan. In commemoration of his vision, the train station’s address is Place Salvador Dali and, in 2010, a shopping centre in the station was named with Dali’s label: El Centre del Mon. The city’s authorities have clearly capitalised on the various labels that have been given to Perpignan and proudly display this to the world.

Thanks to advocacy groups who educate locals on Perpignan’s long Catalan history, and due to its close proximity to Spanish Catalonia, there is now a greater appreciation for its origins. Perpignan has been nationally and internationally recognised to represent Catalonian culture in France, and this continues to shape the city and its inhabitants. Earlier, I asked whether Perpignan is a French or Catalan city; the two titles (capital of Catalan Culture and El Centre del Mon) make a strong case for Perpinyà. Yet, I believe that we no longer have the luxury to simply isolate these identities; the two cultures must now coexist to create a thriving city for its locals and tourists. I think Perpignan has started this process and, with its continuation, it could become a model for other cities who have similar issues with bicultural identities.

Written by Cassia Wydra

Bibliography:

Images:

Perpignan, Les Pyrenees Orientales, Accessed Feb 4, 2025. https://www.les-pyrenees-orientales.com/Villages/Perpignan.php?allphotos#Galeries.

Le Castillet, Les Pyrenees Orientales, Accessed Feb 4,2025. https://www.les-pyrenees-orientales.com/Patrimoine/Castillet.php.

Sandrine, “Le Bras de Venus.” La Gourmandise Selon Sandrine. Feb 5, 2017. Accessed Feb 4, 2025. https://lagourmandiseselonsandrine.blogspot.com/2017/02/le-bras-de-gitan-ou-bras-de-venus.html.

“Boles de Picolat.” La Recette du Dredi! April 15, 2016. Accessed Feb 4, 2025. http://blog.deluxe.fr/cuisine/boles-picolat.html.

“El Centre del Món.” El centre del món. Accessed Feb 4, 2025. https://www.elcentredelmon.com/presse/.

“La Gare de Perpignan” Dali Paintings. Accessed Feb 4, 2025. https://www.dalipaintings.com/la-gare-de-perpignan.jsp.

Tables:

Baylac Ferrer, Alà. Le catalan en Catalogne Nord et dans les Pays Catalans. Perpignan: Presses universitaires de Perpignan, 2016. https://books.openedition.org/pupvd/40095.

Secondary Reading:

Websites:

Meriot, Joane. “Perpignan : quel avenir pour le “centre Del Mon” ?” Franceinfo 3 occitanie. Accessed December 20, 2016. https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/occitanie/pyrenees-orientales/perpignan/perpignan-quel-avenir-centre-del-mon-1158989.html.

Perpignan- Les Pyrénées Orientales, Accessed 4th Feb 2025. https://www.les-pyrenees-orientales.com/Villages/Perpignan.php.

“Gastronomy Catalan cuisine” Perpignan Méditerranée Tourisme, accessed 13th February 2025. https://www.perpignanmediterranee-tourisme.com/en/a-vivre/nos-experiences/gastronomie-et-specialites/la-cuisine-catalane/#:~:text=Boles%20de%20picolat%2C%20cargolade%2C%20mussels,are%20not%20to%20be%20missed.

Baylac Ferrer, Alà. Le catalan en Catalogne Nord et dans les Pays Catalans. Perpignan: Presses universitaires de Perpignan, 2016.

Lipovsky, Caroline. “The linguistic landscapes of Girona and Perpignan: A contrastive study of the display of the Catalan language in top-down signage.” Journal of Catalan Studies 2, no. 21 (2019): 150-194.

Marley, Dawn. “La situation linguistique à Perpignan.” Plurilinguismes 17, no. 1 (1999): 157-181.

Vidal, Pierre. Histoire de la ville de Perpignan depuis les origines jusqu’au Traité des Pyrénées. Paris: H. Welter, 1897.

Vigouroux, Michel, and Robert Ferras. “Perpignan: ambiguïtés d’une ville catalane.” Revue géographique des Pyrénées et du Sud-Ouest. Sud-Ouest Européen 48, no. 2 (1977): 221-230.