Was Britain Ever Really a White Country?

War, empire, and nationhood have defined British history for centuries, from the conquest of Romans to the British Empire and colonialism; but what is it that underlines them all? Whiteness. The unfortunate truth is that, for centuries, Black history has been written out of the narrative; Black people and Black achievements have been ignored and cast out from mainstream accounts. Most people may assume that the first Black people to permanently settle in Britain, outside of slavery, came upon the Windrush in 1948: that is simply not the case. Black history has been synonymous with struggle, inequality, and hardship. To demonstrate this, when you search ‘Windrush’ on Google, the first thing that would appear is scandal. When one looks behind the rose-coloured glasses of whitewashed history, one would see that Black history is the pinnacle of Britain; without Black labour and struggle, Britain would not be the country it is today. Therefore, for all the blood, sweat, and tears that have been given to this country, the erasure of Black history is both harmful and dangerous; the summer 2024 riots by the far-right proved just that. White British extremists chanting for people of colour to ‘go back to their countries’ undermines the constant presence of Black people alongside our white counterparts in Britain. As Black British rapper Dave wrote in his song Black, “Black is strugglin’ to find your history or trace the s**t. You don’t know the truth about your race’ cause they erasin’ it.” The depth of our history has gone unnoticed for far too long. This article attempts to uncover a small part of our vast history and unmask the brilliance of Black people in Britain through exploring two undervalued periods of Black history: Black presence in ancient Britain, and Black people during the Tudor period.

Early Black Presence in Britain

The words of Peter Fryer, a prominent historian, have always resonated. He wrote, “there were Africans in Britain before the English came here,” a sentiment echoed by historian Paul Edwards in his statement: “it would be nice irony against racist opinion if it could be demonstrated that African communities were settled in England before the English invaders arrived from Europe centuries later.” This very idea has unnerved and upset many within the academic community. V.S. Naipaul lamented that “this absurd supposition of Africans inhabiting Britain before the English only goes to show how our once esteemed centres of learning, Oxford and Cambridge, have been insidiously eroded by a dangerous dogma that, very like IS today, wrought misery and havoc in Russia, China and the Eastern bloc, where for all practical purposes it has failed.”

Unfortunately for Naipaul, DNA evidence proves otherwise. In February 2018, the groundbreaking discovery of ‘Cheddar Man’ was made. Research conducted by the National History Museum revealed that Cheddar Man, a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer who lived around 10,000 years ago in Britain, had dark skin (typically associated with the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa), dark hair, and blue eyes. Scientists concluded that it is likely that the majority, if not all, of Europe resembled Cheddar Man during this time, making many of the earliest Europeans ‘Black.’ Dr Tom Booth, a researcher who worked closely with the museum, said that, “until recently it was always assumed that humans quickly adapted to have paler skin after entering Europe about 45,000 years ago.”

Similarly, many other discoveries of Black presence in ancient Britain have been made. In our own city of York, the ‘Ivory Bangle Lady’ was discovered at the beginning of the twelfth century. She was an important woman of North African origins who had resided and died in Eboracum (Roman York) more than 1,700 years ago. She was buried with a number of special objects which highlighted her elevated status and wealth, one such being the ivory bracelets that bore her wrists. Moreover, she wore an intricate blue-glass beaded necklace on her neck, yellow glass earrings, and was found with a blue glass bottle (that was potentially once filled with perfume oil). The discovery of the Ivory Bangle Lady sheds an incredibly interesting light on the inhabitants of the city of Eboracum and Yorkshire during the Roman period. Like the Ivory Bangle Lady, many migrants from Africa and the Near East would have resided in Eboracum, making it a very diverse area. One example of this would be the Emperor Septimius Severus. He was an ‘African emperor’ of Libyan and Berber origin, who stormed Britain with his thousands of troops and lived in Eboracum from 208 CE until his death in 211 CE. Additionally, Quintius Lollius Urbicus (who came from what is now Algeria) was Governor of Britain from 139 – 142 CE and oversaw the building of the Antonine Wall in Scotland. Additionally, further evidence of African settlement has been found in ‘Roman head pots’ of North African design, discovered in York, Chester, and other sites in Scotland.

The Roman Empire spanned from Rome, to Eastern Europe, to North Africa. Diversity was deep within the intrinsic DNA of the Roman Empire. Therefore, it would be a gross misrepresentation to portray Roman England as entirely white in racial makeup. It is naturally true, as the critics say, that not all African soldiers stationed at Hadrian’s Wall permanently settled in Britain; however, one cannot concur that “there is no evidence they ever settled here.” Since the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, this aspect of history has attracted more recognition. Individuals such as Lavinya Stennet have lobbied MPs, such as the former Education Secretary Gavin Williamson, to get topics like this taught in schools as part of the compulsory curriculum. However, this fight to get these subjects more widely taught is not over yet. In the words of Tre Ventour-Griffiths, “if we should take anything away, it’s that Roman Britain is one of the most-taught topics in schools and the fact heritage, geography and identity don’t play a role is an indictment on an establishment in denial of its past and its present.”

Black Tudors

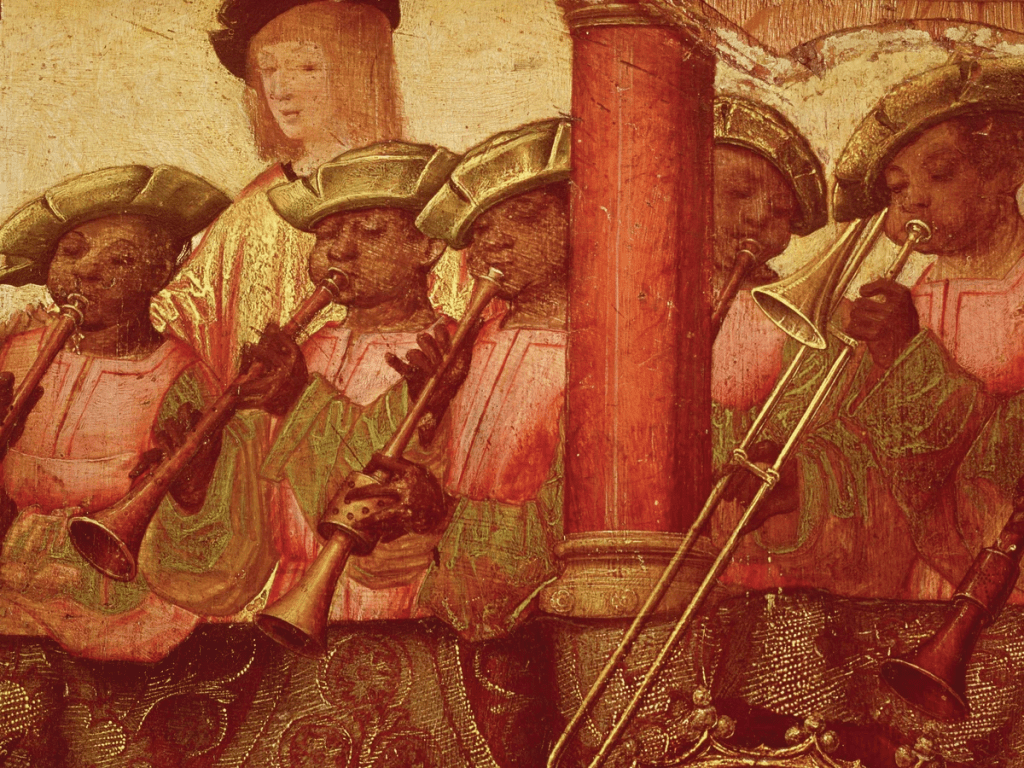

The Tudors are one of the most famous royal families in history. Their reigns, categorised by social, economic, and political upheaval, have inspired art, literature, film and TV for centuries. Despite being one of the most researched periods in history, there is little recognition of the Black people who not only lived in Tudor society, but also moved amongst the era’s most influential figures. To illustrate this, there were many Black people within the households of Sir Walter Raleigh, Robert Dudley (Earl of Leicester), the Earl of Northumberland, Sir Francis Drake, and William Cecil (Lord Burghley). Furthermore, there were over 300 recorded Africans living in larger towns and cities such as London and Plymouth and some smaller towns like Blean in Kent. Thanks to the research of many historians, such as Miranda Kaufmann, Imtiaz Habib, and Hakim Adi to name but a few, we now know that African presence in Britain was not that of enslavement; rather, most Black people during the Tudor era were cooks and domestic servants in paid employment. In fact, at this particular time, slavery had no legal status in Britain: “when the question arose in an English court of law in 1569, it was resolved that England has too pure an Air for Slaves to breathe in.” This was in relation to the case of Pero Alverez, an African man who had come to England from Portugal and was declared a free man. Twenty years later, William Harrison wrote in his Description of England that, “as for slaves and bondmen, we have none, nay such is the privilege of our country… if any come hither from other realms, so soon as they set foot on land they become as free in condition as their masters, whereby all note of servile bondage is utterly removed from them.”

John Blanke and Catalina of Motril are examples of this. John Blanke was a trumpeter working in the service of Henry VII and Henry VIII. He was depicted on the Westminster Tournament Roll of 1511, the only identifiable portrait of an African in Britain during the Tudor period. The circumstances surrounding his arrival in England are still contested by historians, but it is widely speculated that he arrived as part of Catherine of Aragon’s entourage to England when she married Prince Arthur; alternatively, he may have also arrived in January 1506, when Catherine’s sister, Juana of Castile, and her husband Philip were shipwrecked in Dorset. What is significant, however, is the idea that his arrival in England revoked his servitude. Blanke was known to be paid a wage of 8d a day whilst working in the King’s service, with an annual wage of £12: twice that of an agricultural worker. Moreover, his talents were so greatly valued that he was even able to successfully negotiate a pay rise from Henry VIII. The King even paid his wedding bill in January 1512, gifting Blanke a gown of violet cloth, a bonnet, and a hat. Catalina of Motril was also a maid for Catherine of Aragon. She too accompanied Catherine to England and was most likely forced to convert to Christianity by Isabella and Ferdinand of Castile so that she could join Catherine’s household. Catalina played a crucial role within Catherine’s household as it would have been her duty to make the Queen’s bed, help her dress, and she would have been there during Catherine’s isolation periods whilst she was pregnant and often miscarried. Her role in attending to Catherine’s chamber also meant she was present for both of Catherine’s wedding nights in 1501 and 1509, making her a very sought after witness for Henry’s divorce trials. However, by this time she had already returned back to Spain and had married a Moorish cross-bow maker named Oviedo.

It is no surprise that when most people think of Black people during Tudor times, they think of slavery; this article has proved that this was not always the case. This is not, however, to suggest that all Black people in London lived discrimination-free lives. Thomas More wrote to his friend, John Holt, that Catherine’s entourage was “laceri nudipedes pigmei Ethiopes” (hunchbacked, barefoot Ethiopian pygmies). Moreover, the status of Catalina has often been debated: was she still enslaved in England in all but name? There is no evidence to suggest that she ever got paid for her services, and even 30 years after leaving Catherine’s service, Catalina was referred to as “once the Queen’s slave,” or “esclava que fue,” meaning the ‘slave that was.’ However, this does suggest that she had been enslaved in Spain, but free in England. What cannot be taken for granted is the importance of Black Tudors such as John Blanke and Catalina of Motril. Catalina was one of few people to truly know if Catherine’s marriage was ever consummated with Prince Arthur: had she been questioned about this during Henry VIII’s divorce trials, would the course of history have been different?

Conclusion

To answer the question of this article, no, Britain has never truly been an ‘all white’ country. Just by taking a look at two periods of history often overlooked in terms of significance for Black history in Britain, one can see that Black people have been present from the birth of Britain. Since the time that Britain was geographically attached to Europe, Black people have found their home in this country. In the Tudor era, they found their freedom in Britain, just as John Blanke, Catalina of Motril, and Pero Alverez did. Whilst people chant racist language in the streets today, our ancestors lay buried deep within British soil, serving as a reminder that we have roots in this country. Black history is still British history. The hardships faced by Black people must not be forgotten, but when one grows up within an education system where Black history does not exist outside of bondage, subjugation, or migration, it is easy to ignore our success and influence, found in individuals such as John Blanke or the Ivory Bangle Lady. British history is extremely deep and multifaceted, and the recognition of all its past is necessary for our modern day society to function.

By Sinead Bedward

Bibliography:

1511 Westminster Tournament Roll showing John Blanke. National Portrait Gallery. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/john-blanke-and-the-westminster-tournament-roll.

Adi, Hakim. “African and Caribbean People in Britain: A History.” Penguin Books, 2023.

Barnes, Tom; Channel 4. “Close up of the model of Cheddar Man rendered by Kennis & Kennis Reconstructions.” Natural History Museum. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/cheddar-man-mesolithic-britain-blue-eyed-boy.html.

Birley. A. “Septimus Severus: The African Emperor.” Routledge, 1999.

Branagan, Mark, Craven, Nick. “GCSE pupils to be taught that the nation’s earliest inhabitants were Africans who were in Britain before the English.” Mail Online, 9 January 2016. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3392088/GCSE-pupils-taught-nation-s-earliest-inhabitants-Africans-Britain-English.html.

Bridgemanimages.com. “Black musicians in a Portuguese painting of the Engagement of St Ursula and Prince Etherius, c1520.” The Guardian, 29 October 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/29/tudor-english-black-not-slave-in-sight-miranda-kaufmann-history.

Edwards, Paul. “The early African presence in the British Isles.” In J.S. Gundara, I. Duffield, Essay on the History of Blacks in Britain. Aldershot, 1992.

Fryer, Peter. “Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain.” Pluto Press, 1984.

Habib, Imtiaz. “Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible.” Routledge, 2008.

Historicallycandles. “The Ivory Bangle Lady.” 2023. https://historicallycandles.co.uk/blogs/historically/the-ivory-bangle-lady-black-history-month.

Kaufmann, Miranda. “Black Tudors: An Untold Story.” Oneworld Publications, 2017.

Lotzof, Kerry. “Cheddar Man: Mesolithic Britain’s blue-eyed boy.” Natural History Museum, 2018. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/cheddar-man-mesolithic-britain-blue-eyed-boy.html.

McKie, Robin. “Cheddar Man changes the way we think about our ancestors.” The Guardian, 10 February 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/feb/10/cheddar-man-changed-way-we-think-about-ancestors.

Sanchez Gallque, Andres. “The Mulatto Gentlemen of Esmeraldas.” 1599.

Selly Manor Museum. “Black Tudors: free men and women in England.” 2 October 2023. Accessed 30 October 2024. https://sellymanormuseum.org.uk/news/2023-10-02/black-tudors-free-men-and-women-in-england.

Ventour-Griffiths, Tre. “Afro-Romans: “There were Africans in Britain before the English came here.” Medium, 13 March 2021. https://treventour1995.medium.com/afro-romans-there-were-africans-in-britain-before-the-english-came-here-f336c5449759.

York Museum Trust. “Celebrating Ivory Bangle Lady.” Accessed 20 October 2024. https://www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/blog/celebrating-ivory-bangle-lady/.