The Stories Behind Brit Bennett’s ‘The Vanishing Half’: Racial Passing in Twentieth Century USA

The Vanishing Half (2020) depicts the story of countless mixed-race African Americans in the twentieth century. Whilst it may at first seem a uniquely fictional story, in reality many Americans can empathise and relate to it. Brit Bennett beautifully weaves together the stories of two generations, creating a narrative of belonging and identity. Through the life of Stella Vignes, Bennett tells a story of racial passing.

‘Passing’ is the phenomenon in which a person portrays themself, and is commonly perceived, as a different identity from the one they were originally born into. Whilst passing can be used in the context of any identity, for example a person’s sexuality or gender, for the purpose of this discussion, it will refer to a Black (or mixed-race) person passing for white. This is often described by academics as ‘crossing over’ the racial divide.

The two protagonists of The Vanishing Half, Stella and her twin sister Desiree, were born into the small fictional town of Mallard. The town, founded by a freed slave (born to a slave owner and an enslaved woman), distinctly prioritises skin lightness. Mallard’s inhabitants inter-marry in order to lighten their descendent’s skin over generations, described as “lightening the line.” The twins, therefore, undoubtedly inherit a complex understanding of racial identity, one that is explored throughout the novel. The Vanishing Half follows Desiree and Stella throughout their lives; their experiences of work, marriage, and motherhood, all intertwined with their racial identities. Stella, after escaping from Mallard to New Orleans with Desiree, passes as white for a better job opportunity, one that would not have been available to her as a Black woman. This seemingly inconsequential decision leads her down the road of no return. Stella spends the rest of her life passing as a white woman, marrying a white man, and raising her daughter as white. The book’s comparison of Stella’s and Desiree’s lives—Desiree living as a Black woman and raising a dark-skinned daughter—further underscores the complexities of racial passing. Through this narrative, Bennett presents a compelling discussion of the true stories of those who did racially pass in twentieth century USA.

Case Studies

In 1896, the Supreme Court, in the Plessy v Ferguson ruling, declared racial segregation as legal. The famous conclusion, resulting in the ‘separate but equal’ justification, consolidated racial identities as binary. African Americans experienced their identification by the government as almost solely racially based.

However, passing inherently negates this. By understanding the examples of those who ‘crossed the racial divide’ during the twentieth-century historians have come to some thought-provoking conclusions. One issue is the implicit nature of racial passing. Those who passed ‘successfully’ were never discovered, and it is possible that their families continue to live without the knowledge of their heritage. Thus, their stories are never shared publicly and there is subsequently little concrete evidence that points directly to a person’s story. Despite the challenges that historians face, there are some examples which can aid us in understanding this phenomenon. The cases presented in this article are possibly some of the most accessible examples, and therefore they allow in depth analysis. Alongside this, there is a significant opportunity here for parallels to be drawn between the true stories and the narrative that Bennett tells of Stella and her family. Nevertheless, it remains true that these instances of racial passing are not clear-cut and do not provide simple answers to the complex questions that surround this discussion.

One interesting example is that of Susie Guillory Phipps who pursued a 1982 legal case in which she campaigned to change her racial classification on her birth certificate. Phipps discovered that she had been classified as Black; however, she contested this. In Louisiana state law, a person was considered Black if they were at least one-thirty-second ethnically Black (or 0.03125 percent) – Susie Phipps fell under this category. Despite Susie’s persistence that she was white, pointing to her face as evidence, the state denied the case. Lawyers had traced her genealogy back 222 years to an enslaved woman named Margarita, and this evidence was used to establish that Susie could not legally be considered white. Whilst Phipps perceived herself a white woman, she lived her life and presented herself as something the state believed her not to be. Therefore, this case can be understood as an example of racial passing. However, Phipps likely would not have classified her experience in this way, and this presents a significant challenge for historians. It is difficult to impose the definition of racial passing on her story without some careful consideration. With this consideration, though, Phipps’ example provides significant insight into the flexibility of race in American society. Whilst the American government strove to define race as something fixed and binary, the existence of racial passing as a phenomenon overturns this idea. Additionally, Phipps’ case presents the fluidity of passing, something that will continue to be reinforced throughout this examination.

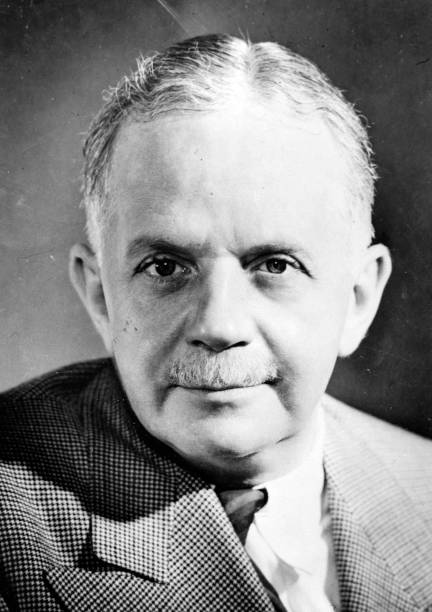

The case of Walter White adds another facet to this discussion. Walter White was a prominent member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). White utilised his ‘white-presenting’ features of light skin, hair, and eyes to contribute towards campaigns against racial violence. From 1918 to 1930, White investigated lynchings and race riots whilst passing as white in order to gather information. His appearance permitted him to talk to members of the Klu Klux Klan and other extremist organisations which never would have been possible had he disclosed his racial identity. However, White did not ‘cross over’ the racial divide permanently. Through his role in the NAACP, he immersed himself in the African American community and was proud of his racial heritage. This example indicates that racial passing did not always mean living within a white identity, and clearly exposes how passing is a unique and individual experience that differs from case to case. White’s example additionally allows us to understand a reason for passing: it allowed access to spaces which would have been inaccessible otherwise, as Bennett’s character Stella also exemplifies.

Marriage is another notable method of passing, or at least facilitates the reinforcement of a manufactured identity. Both men and women, but perhaps more notably the latter, married white Americans and assimilated into their families. Marriage is an integral part of Stella’s story in The Vanishing Half, with family life and identity being important to her struggle to continue to pass as white for her whole life. A true, but complex, example that can perhaps aid our understanding of racial passing is that of the Rhinelander case. Although there remain many gaps in this story, it does reveal contemporary attitudes concerning ideas of racial passing, and its common understanding as an act of deception. Leonard Kip Rhinelander was a wealthy, white socialite who secretly married a working class woman named Alice Jones. When news of this union broke, it was declared a scandal. During the press’ unfolding of the story, it was published that Alice Jones was in fact a woman of colour. In November 1924, Rhinelander filed for annulment of the marriage on the basis of fraud, claiming that Jones had deceived him and presented herself as white. Over the course of the highly publicised trial, it became evident, however, that Rhinelander was aware of his wife’s racial ancestry and thus the annulment was denied. The discourse surrounding the scandal reveals to us how racial passing was understood at the time. Jones’ actions were painted as insincere and deceitful. She was degraded and interrogated by Rhinelander’s lawyers as if she were a dangerous criminal, even going so far as to order her to partially undress in the courtroom so she could display her skin colour. Whilst it can be concluded that Jones did not intend to pass as white, her treatment allows us to conclude that racial passing was seen in a distinctly negative way, as a betrayal and fraud, by both white and Black Americans. Whilst not on this level of degradation, in Bennett’s novel, Stella experiences similar treatment and is accused of betrayal and deceit.

Conclusion

This article’s exploration of cases surrounding racial passing illuminates the impact of Brit Bennett’s novel in opening up conversations, allowing these vital stories to be shared. The story of Stella and her struggles with racial passing presents an accessible entry into the history of this phenomenon and the stories of the real people who experienced it first-hand. Bennett’s tale takes the reader through the ups and downs of passing, but avoids the ‘tragic mulatto storyline’ that is all too common in narratives of this nature. When deploying this ‘trope,’ authors often place emphasis on the devastating, often fatal, stories of mixed-race people. Whilst The Vanishing Half focuses on loss and struggle, it does not centre on this. Instead, Bennett unravels the dynamic nature of identity, and how it can be both beneficial and detrimental. Passing is inherently a flexible process, one which emphasises the mutability of identity and race. The case of Susie Phipps exposes the binary classifications that the state attempted to impose on Americans; however, Walter White’s use of his appearance to pass exemplifies the fluidity of race as something which is not always a fixed distinction. Additionally, examining passing also exposes the attitudes towards race in a striking way, aiding further comprehension. By viewing the history of race in America, an extremely well explored theme, through this lens, new aspects are exposed and can be further explored. Therefore, by telling these stories, Brit Bennett and other authors prompt the conversation which can be furthered by historians, proving once again the value of historical fiction is immeasurable.

Written by Eloise Gibson

Bibliography

Anthony, Arthe A. “‘Lost Boundaries’: Racial Passing and Poverty in Segregated New Orleans”. In Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Colour, edited by Sybil Kein, 295-316. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Barthelemy, Anthony G. “Light, Bright, Damn Near White: Race, the Politics of Genealogy, and the Strange Case of Susie Guillory”. In Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Colour, edited by Sybil Kein, 252-276. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Bennett, Brit. The Vanishing Half.

Hobbs, Allyson Vanessa. “Prologue: To Live a Life Elsewhere”. In A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life, 1-28. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016.

James, Gregory. “Suit on Race Recalls Lines Drawn Under Slavery”. New York Times. Sept 30, 1982. https://www.nytimes.com/1982/09/30/us/suit-on-race-recalls-lines-drawn-under-slavery.html.

Janken, Kennetth Robert. “Chapter 1: Becoming Black”. In Walter White: Mr NAACP, 1-29. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Lewis, Earl and Heidi Ardizzone. “A Modern Cinderella: Race, Sexuality, and Social Class in the Rhinelander Case”. International Labor and Working-Class History 51 (1997): 129-147.

Morgado, Monica Garcia. “Colorism, passing for white, and intertextuality in Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half: Rewriting African American Women’s Literary Tradition”. Babel Afial 31 (2022): 73-96.

Images

Gado, Afro Newspaper. “Walter White Portrait”. Photograph, Getty Images, 1940.

Lee, Russell. “Segregated Fountain”. Photograph, Library of Congress, 1939.

Taylor, Nico and Jo Taylor. “The Vanishing Half Cover”. In The Vanishing Half. London: Dialogue Books, 2021.