A Concealed History: The Great Pavement of Woodchester

The Orpheus Roman Pavement

If one was to travel back in time to the Ancient Roman Empire, one would find themselves in a world overrun by art. Beautiful bronze and marble statues lining roads and pavements, intricate murals and expertly crafted frescos on the walls inside beautifully designed architecture – the Ancient Romans were aesthetes before the Aesthetic Movement was even a seed of thought in the mind of revolutionary artists.

Roman society valued all forms of artistic expression, but the mosaic floors were held in their highest regard. To their society, the quality and quantity of mosaic floors within a property was an expression of wealth, and the style of the floor showed what was popular at the time it was created. Typically, Roman art would depict highly regarded individuals from real life and mythology to reinforce their powerful, authoritative, and cultural identity within the world.

Incredibly, the largest mosaic floor rediscovered in Northern Europe was found in a quaint, little Cotswold village in Gloucestershire.

Uncovering the Pavement

After being lost for centuries, the mosaic was rediscovered in 1693 by the Celtic scholar Edward Lluyd after he visited a churchyard in the village of Woodchester. It was then recorded for the first time in Richard Gough’s Additions to Camden’s Britannia and acquired the name ‘The Great Pavement’ in 1797 after antiquarian Samual Lysons referred to it as such in his work.

The mosaic was created by craftsmen from Corinium (Cirencester), dating to around 325 CE and contains around one-and-a-half million stone pieces. It was part of a villa that was created during the reign of Hadrian (r.117-138 CE) when the Cotswold province was one of the richest in Roman Britain. It has been described as the most elaborate mosaic uncovered in Britain by far. This indicates that the floor that Woodchester churchyard was built upon had belonged to the property of a sufficiently wealthy Roman, perhaps even one that controlled the area of modern-day Gloucestershire during the Roman occupation. Some historians theorise that it was a summer palace belonging to the Governor of western England and Wales due to its convenient location; between the local capital of Cirencester and Caerleon, the military base in South Wales, the location of the theorised summer palace would be perfectly centred between both. Although mere speculations, it can begin to explain why a mosaic of this calibre is seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

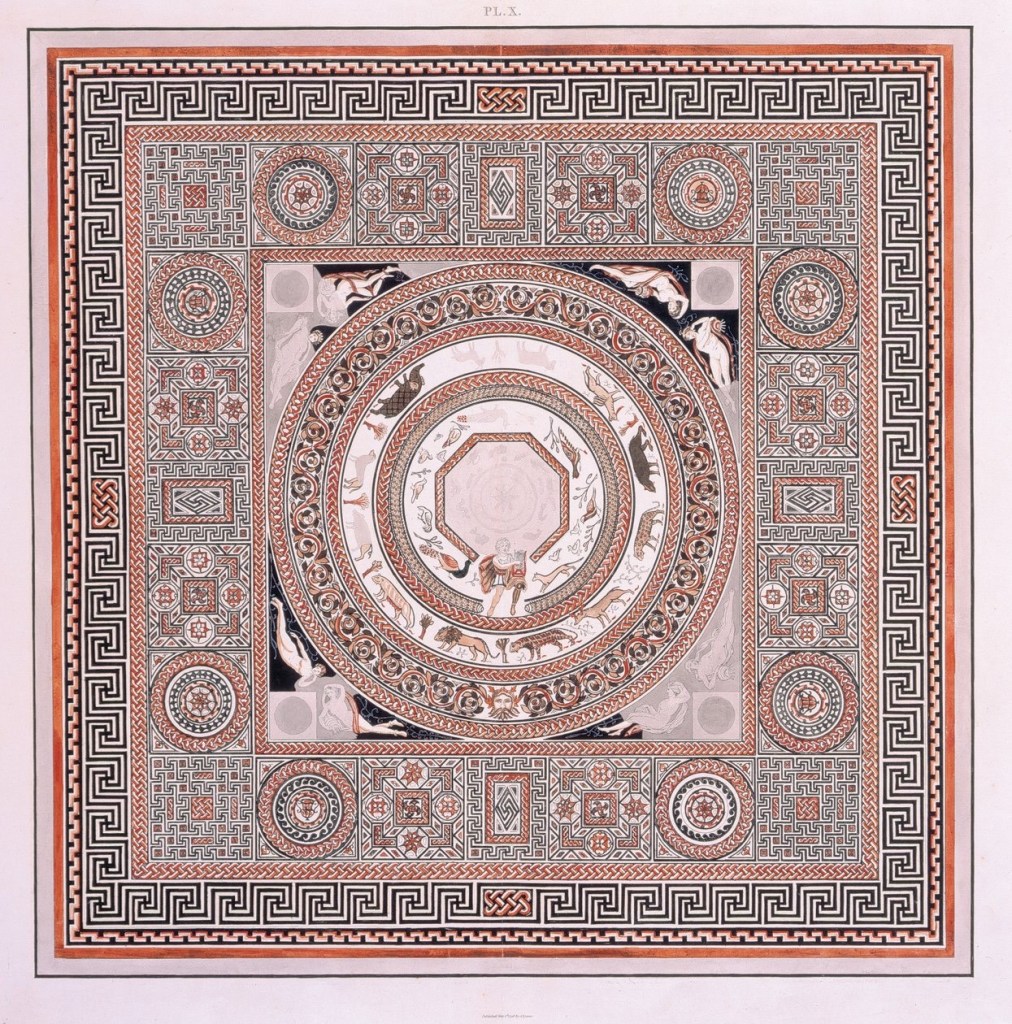

Although not proven to belong to a specific person, the mosaic appears to have been a centrepiece for a twenty-two acre palace complex from around 200-400 CE – the mosaic itself is 2,200 square feet in size – and it depicts a scene from the mythology of Orpheus, a popular choice in individuals for Roman mosaic art. Orpheus mosaics have been found throughout the areas that were once a part of the Roman Empire dating between the second century and the fifth, a demonstration of how beloved the stories of Orpheus were.

The Myth of Orpheus

The pavement’s position on the floor allows the scene to be understood from all angles. In the centre is Orpheus accompanied by his lyre. Surrounding him are wild creatures and nature in an impressive array of geometric designs, eliciting a sense of cohesion and order. Unlike other great individuals used within Roman art, Orpheus is able to control the natural world through the lull of his song, without violence or physical strength. His central position allows one to understand that he has incredible influence over nature simply through his artistry.

In Roman and Greek mythology, Orpheus is the quasi-deity son of Apollo and a Muse. He possesses the ability of song, surpassing that of a normal human’s talent, and it is this feature of Orpheus that is celebrated the most in his stories. In Greek mythology, according to Homer’s The Odyssey, he is the hero who saves the Argonaut’s from the Sirens. The Argonauts were fifty heroes who were sent to retrieve the Golden Fleece on the ship Argo, led by Jason whose uncle had usurped the throne that had rightfully belonged to his father. As is the case with most heroes, the Argonauts encountered Sirens – beautiful women who would lure sailors to their death through their irresistible song. It was Orpheus who saved the men from their deaths by playing a song that rivalled that of the Siren song, allowing the Argo to pass safely.

Orpheus’ main myth, however, was about the tragedy surrounding the death of his love, Eurydice. Narrated by the Roman poet Virgil, Eurydice dies shortly after her marriage to Orpheus due to a poisonous snakebite. To save her, Orpheus travels to the underworld and uses his song to enchant Hades. In a brief instance of hope, Orpheus’ song gains Eurydice a second chance of life if, when leading her out of the afterlife, he does not look back at her until they have both left the underworld. Tragically, in all versions of this myth, Orpheus fails to not look back at Eurydice and loses her forever.

Orpheus mosaics typically show an artistic retelling of what occurs after the loss of his wife. After failing to bring Eurydice back from death, Orpheus retires to the natural world in grief. He plays a song of a lament which attracts the animals, trees, and rocks, gaining power over nature itself through his artistry alone. Orpheus’ death, at the hands of a group of women (not specified as there are several versions that describe different explanations for who these women are and what their motive was), does nothing to silence him as his head continues to give prophecies on the island of Lesbos.

In all stories, Orpheus’ most powerful aspect is his song. It is his artistry that gives him power, as opposed to other heroes such as Hercules (Heracles) or Achilles who used brute strength and violence to achieve what they desired. Perhaps this is why the myth of Orpheus was a popular choice for artistic design, as a scene of him taming nature with the lyre evokes a powerful sense of harmony and peace which a story of violence could never achieve. To understand its full emotional impact it would be nice to observe the mosaic in person. However, the real Great Pavement of Woodchester is once again concealed from view.

A Lost Replica

After the Great Pavement was rediscovered in 1693, it was uncovered for the public every ten years until 1973 when the villagers of Woodchester made the decision to cover it up until further notice. This was caused by an onslaught of 140,000 tourists in the area over a seven-week period that caused utter chaos in the village. It was not only damaging to the community and the environment, but also the mosaic itself. As a result of this decision, a replica was created of the mosaic floor so that people could still see what it looked like without causing damage to the original floor and the village of Woodchester.

The replica took a decade to complete, over the 1970s and 1980s, and was the work of brothers Bob and John Woodward. They used 1.6 million pieces to recreate the Orpheus mosaic and strived for an exact copy of the piece. Unfortunately, they were forced to sell this replica in the 1990s. The replica resurfaced in 2010 at an auction and a petition was started by the residents of Woodchester to gain it back. However, they were outbid by an anonymous Italian buyer who paid £75,000 for the replica. As of 2018, an investigation into the replica’s whereabouts claims that this piece was bought to be installed in a private villa at Lake Como but was never used, so it is currently still in storage.

Although missing the opportunity to return the replica back to the village it originated from, the residents of Woodchester are reportedly satisfied with the fact that they are still in possession of the original mosaic despite its indefinite concealment.

Written by Charlotte Mandefield

Bibliography

Buchan, M. (2022). Don’t Look Back? Orpheus and Eurydice Today. [online] The Paideia Institute. Available at: https://www.paideiainstitute.org/don_t_look_back_orpheus_and_eurydice_today.

Clarke, G., Rigby, V. and Shepherd, J.D. (1982) ‘The Roman villa at Woodchester’, Britannia, 13, pp. 197–228. doi:10.2307/526494.

Graf, F. (2016) Orpheus | Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford Classical Dictionary. Available at: https://oxfordre.com/classics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-4611 (Accessed: 10 September 2024).

The Great Pavement of woodchester roman mosaic floor (2024) Nicholas Wells Antiques Ltd. Available at: https://nicholaswells.com/product/orpheus-pavement-roman-mosaic-floor/ (Accessed: 10 September 2024).

History of the area (2024) Woodchester Valley. Available at: https://www.woodchestervalleyvineyard.co.uk/about/area-history (Accessed: 10 September 2024).

Morgan, T. (2017) ‘Romano-British Mosaic Pavements’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 38(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00681288.1882.11887808.

Scott, S. (1995) ‘Symbols of power and nature: The orpheus mosaic of fourth century Britain and their architectural contexts’, Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal, 0(1992), pp. 105–123. doi:10.16995/trac1992_105_123.

Smith, D.J. (1969) ‘The Mosaic Pavements’, in The Roman Villa in Britain. 1st edn. London: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003483458 (Accessed: 10 September 2024).

The Great Pavement of woodchester roman mosaic floor (2024) Nicholas Wells Antiques Ltd. Available at: https://nicholaswells.com/product/orpheus-pavement-roman-mosaic-floor/ (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Watson, S.P. (2018) Roman replica will not return despite villagers’ £150,000 bid, Stroud News and Journal. Available at: https://www.stroudnewsandjournal.co.uk/news/17311876.roman-replica-will-not-return-despite-villagers-150-000-bid/ (Accessed: 21 September 2024). Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DSC00355_-_Orfeo_(epoca_romana)_-_Foto_G._Dall%27Orto.jpg (Accessed: 21 September 2024).