The Three Wise Men: Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and the Legacies of Assassination

1. The State of the Union, 1953

It was January 1953, and John F. Kennedy was clearing out his office. He was leaving the House of Representatives. His wealthy Irish-American family had long wanted one of their own to hold high office, and their plan was falling into place. The baby-faced war hero had just won election to the Senate as a Democrat representing Massachusetts, and Kennedy was one step closer to the presidency.

The office opposite to his also stood empty. When Kennedy had first come to Congress in 1947, that office had been occupied by Richard Nixon, who himself had much to celebrate in 1953. He was to be Vice President in the first Republican administration since the 1930s. As Kennedy and Nixon swore their respective oaths and a new chapter of American history began, it seemed everyone was moving up in the world.

Everyone, that is, except for Lyndon Johnson. The Democratic Party leader in the Senate had been hoping for a majority in 1952, but had received bitter disappointment and the pyrrhic title ‘Minority Leader’. His long career in Texas politics had given him the reputation of a formidable legislator, and he wanted to prove himself. Eventually he would, but for the moment, he swallowed his pride, as the new Senator Kennedy basked in the spotlight.

Even at this early stage, these three individuals were larger than themselves. Kennedy embodied the class of wealthy eastern elites who had grown more liberal and powerful since the war. Johnson was a traditionalist Democrat who represented the white-skinned blue-collar worker. Nixon’s childhood had been a poverty-stricken struggle in rural California, and he saw nothing more contemptible than Washington DC. So, naturally, he strove to conquer it.

These three men embodied the three nations which existed in the post-war US. Kennedy; Johnson; Nixon. New-Money America; Old-Guard America, and Left-Behind America.

2. Candidates

From 1953, these three men built their brands and set up their stalls for the 1960 election. Senator Kennedy created a powerful coalition, courting trade unions and CEOs alike. Senator Johnson became Majority Leader and used his clout to increase the minimum wage. Nixon’s role as Vice President gave him considerable reach into the living rooms of the American people, but he was most often used as the whipping-boy of the Eisenhower administration.

While they were each powerful in their own ways, one proved victorious. The Civil Rights movement and recessions of the 1950s created an appetite for freshness and renewal, and into this political culture rose Senator Kennedy: the future of the Democratic Party.

The first obstacle he faced was Lyndon Johnson, who rivalled him for the party nomination. Democrat party-members from each state voted for their preferred nominee, and Johnson won comfortably in the South, even in states where he did not campaign. A last-minute financial injection from the Kennedy family pushed JFK’s team over the edge, and in his success, he offered the job of Vice President to Johnson. To political commentators this was a sign of party unity, but for Johnson, it was a constant reminder that he was the second-best.

Kennedy’s next task was to take on the Republicans. As Vice President in a Republican administration, Nixon was the heir-apparent to his party. His campaign came to a rough patch early on, when wealthy Republican donors backed a left-wing challenger of Nixon’s. He took this slight personally, believing Washington elites saw his upbringing as a ranch-worker’s son as a disqualifying factor. Despite this setback, Nixon won the nomination, and faced off against Kennedy.

Nixon’s biographers have all diagnosed his chronic inferiority complex, and nobody made him feel more inferior than the young, stylish, and abundantly rich Massachusetts Senator. The Democratic campaign was a slick operation: an infamous televised debate put Nixon on the back foot, and campaign literature painted him as a creep, a crook, and a warmonger.

The result was a Kennedy victory. In the course of one campaign, Kennedy had pummelled Johnson, Nixon, and the versions of America they each represented.

3. Camelot

The Kennedy Administration was, by any standards, style over substance. Kennedy attempted to table legislation to improve social security and race relations, but his Senate was slow and clogged up by conservatives. Some progress was made on the domestic front, but the only thing which kept Kennedy’s approval ratings above a steady 70 percent was the rolling crisis of the Cold War. This kept manifesting in earth-shattering ways across his term, first with the Berlin Wall, then with the Cuban Missile Crisis. Re-election looked likely, but changes needed to be made to cement it.

In late-1963, a rumour began to spread around Washington DC which horrified Lyndon Johnson. It said that Kennedy planned to choose a new Vice President in 1964. This would be a breach of political norms and would likely end Johnson’s career.

The rumours never became anything more, because, luckily for Johnson, a man named Lee Harvey Oswald was currently travelling from Louisiana to Dallas, Texas, and he had plans for the President.

4. Killing Kennedy

Ineffective though Kennedy was, he kept his opponents at bay. At no stage in his thousand days in office did it look like Johnson’s paternalism nor Nixon’s conservatism were to return. Then, on 22 November 1963, the young president was killed and the vultures descended.

Aboard Airforce One, Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as President beside a bloodstained Jackie Kennedy. While travelling back to Washington DC, members of the Kennedy family and Cabinet sat in one section of the aircraft in grief. Johnson took his own supporters to his quarters of the plane and began to celebrate. The sounds of the newly-ascended President drunkenly toasting were heard across the entire aircraft. Johnson’s relationship with the Kennedys had never been especially close, but this ended it for good.

Nixon’s own response to the assassination was more interesting. He was being chauffeured at the time, and upon hearing the news, he immediately phoned a Republican colleague and demanded to know of the gunman: “Was he one of ours?”. The events appalled Nixon, and although this may seem surprising, it is a perfect encapsulation of the man’s mentality. He saw himself as an underdog, and had risen almost to the very top. His obsession with political power meant he respected those who held it, however begrudgingly.

Now, the man who held that power was President Lyndon Johnson, the first contender Kennedy had batted off in 1960.

5. Rolling Thunder

Kennedy was more useful to Johnson dead than alive, and he did not care who knew it. Kennedy’s inefficiency at getting his legislation passed troubled Johnson deeply across the years, and in the nation’s grief, he saw an opportunity. Decrying the assassination as “the foulest deed of our time”, he called on Congress to honour the martyr by passing a sweeping slate of domestic legislation in Kennedy’s name. This included the abolition of segregation, voting rights for African Americans, and the provision of healthcare for the elderly and poor. Although Johnson comfortably won an election of his own in 1964, his ‘Great Society’ agenda depended entirely on the posthumous legacy he crafted for Kennedy.

Unfortunately, this was also his undoing. Besides an unfinished domestic agenda, Kennedy had also left Johnson a troubling inheritance in South Vietnam. As early as 1961, Kennedy had commenced sending military advisers to Southeast Asia to help fight North Vietnamese Communists. Vietnam had been an important Cold War arena for Kennedy, as it represented Communist infiltration into developing nations. Seeing this commitment as a stance to be vindicated, Johnson expanded on Kennedy’s actions in increments.

Initially, this was received positively, as all anti-Communist measures were during the time. However, over years, the tide turned as both the cost and futility of the war became intolerable to America at large. By 1968, Johnson had wasted over $100 billion, used 860,000 tons of explosives, and committed 540,000 American troops to a war America was clearly losing. Students, veterans, and journalists launched such scathing attacks on Johnson that, faced with calls to resign, he announced he would not stand in the 1968 election. In crafting a powerful legacy for Kennedy, he ruined his own.

Enter Richard Nixon. He made a comeback in the Republican Party and won 1968 with relative comfort. He was the last man standing of the Three Wise Men from 1960. In time, however, the Kennedy curse would claim him too.

6. ‘Tricky Dicky’

Nixon’s first term was unremarkable. He failed on his conservative promises to scale back welfare and win in Vietnam, but he remained popular because the Democrats failed to form a powerful opposition. For a time it appeared that Nixon’s version of America, the ‘silent majority’, had won out over the liberalism, wealth and privilege of Kennedy.

Then, in 1972, the Democrats chose as their presidential nominee a man named George McGovern. He was a liberal Irish-American Senator who energised America’s youth and promised a new style of politics. To Nixon, he was Kennedy-come-again. The President became consumed with the fear that he would again be defeated by the establishment elites. His obsession became so total that his advisers had to intervene.

A secret committee was formed without Nixon’s knowledge, its one job to get him re-elected. This Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) was staffed by only the administration’s shadiest characters: a former-CIA operative, a spy writer, and a small army of Cuban exiles. Any enemy to Nixon’s re-election fell under CREEP’s purview, even those within the administration. When the wife of the Attorney General criticised their phone-tapping, she was tranquillised and divorced. CREEP’s operation overreached in the case of the Watergate Hotel, where the Democrats had their headquarters. CREEP broke into the hotel in May 1972 to bug the place on multiple occasions, eventually getting caught and detained. At this stage, Nixon was brought into the loop to orchestrate a cover-up.

He succeeded initially, winning the most decisive landslide of the postwar era. But he did not relish victory: instead of enjoying re-election, Nixon sequestered himself in the Oval Office beneath Kennedy’s presidential portrait and began writing down what horrible things he predicted the newspapers would say about him.

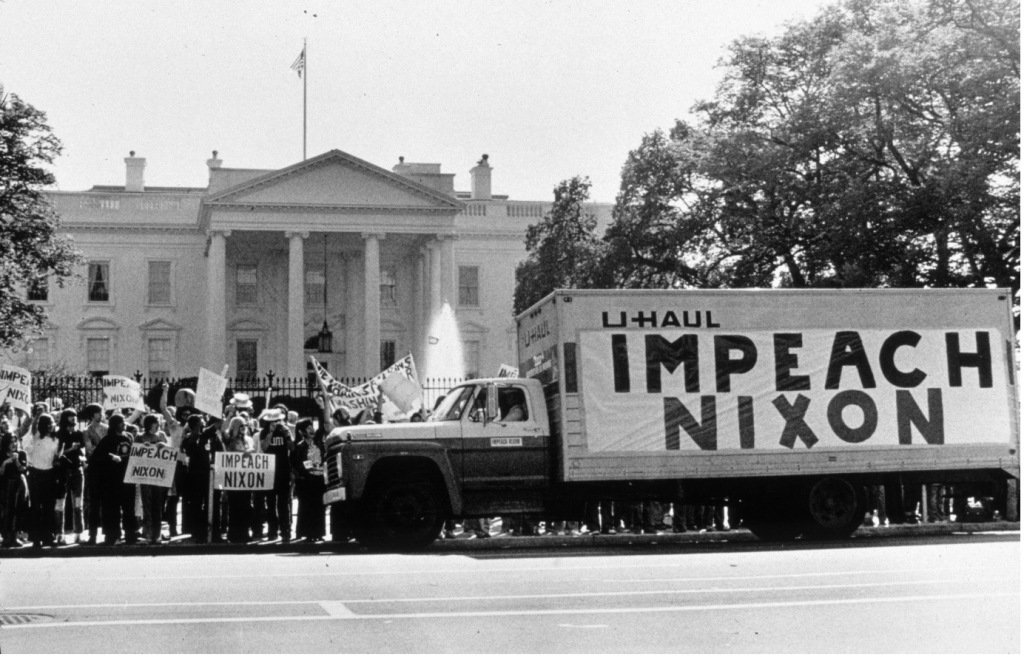

The turning point came when key advisers of his resigned and were convicted. In the summer of 1974 a Senate delegation was sent to the White House, a notable member being Edward Kennedy, brother of the assassinated President. The gathered Senators informed Nixon that Congress planned to impeach him for crimes against the United States.

In the second week of August, Nixon resigned. The presidency was held in the lowest esteem in its history, and has never fully recovered. The fear Kennedy had put in Nixon years ago of being thwarted by the liberal establishment led his administration into the biggest scandal in American history, and tarnished any other legacy Nixon may have had.

7. Conclusion

Johnson and Nixon were handed the poisoned chalice of presidency by Kennedy, and they drank from it eagerly. Johnson felt compelled to finish what his predecessor had started, regardless of the costs, and Nixon defined himself against the privilege Kennedy represented. Their missions, while initially successful, eventually faltered: eroding America’s standing on the international stage, then shattering respect for the presidency. Their standing in American history is clear: Johnson is the butcher of Vietnam, and Nixon, the crook in the White House. But behind these failures there is the silhouette of a young Senator from Massachusetts, who in death tore down his opponents more thoroughly than he ever had in life.

Written by Sam Chapman.

Bibliography

Brennan, Mary C. “Winning the War/Losing the Battle: The Goldwater Presidential Campaign and Its Effects on the Evolution of Modern Conservatism.” In The Conservative Sixties, edited by David Farber and Jeff Roche, 63-79. New York: Peter Lang, 2003.

Gladstone, Mark. “An Election Win in 1960.” Chron. Nov 9, 2013. Accessed Nov 16, 2023. https://www.chron.com/opinion/outlook/article/with-an-election-win-in-1960-jfk-marked-a-shift-4970536.php.

History.com Editors. “Lyndon B. Johnson.” History.com. Oct 29, 2009. Accessed Nov 16, 2023. https://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/lyndon-b-johnson#&pid=nixon-and-johnson.

Johnson, Lyndon Baines. Let Us Continue. Washington DC, 1963. American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank. Access November 11 2023. https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/lbjletuscontinue.html.

Mason, Robert. The Republican Party and American Politics from Hoover to Reagan. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of American Consensus. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001.

Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland. United States: Scribner. 2009.

Perlstein, Rick. The Invisible Bridge. United States: Scribner. 2014.

Sanders, Vivienne. The American Dream: Reality and Illusion, 1945-80. London: Hodder Education. 2015.

Schoenwald, Jonathan M. A Time For Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Seib, Gerald F. “Why Watergate Lives On.” Wall Street Journal. Aug 4, 2014. Accessed Nov 16, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-watergate-lives-on-40-years-after-nixon-resignation-1407167209.

Zelizer, Julian E. Governing America: The Revival of Political History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.