Fothergill – An exploration of the architectural vernacular of Nottingham

An Introduction

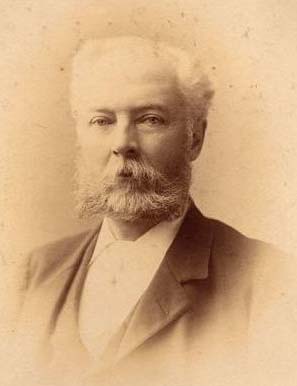

Watson Fothergill was born as Fothergill Watson in Mansfield, North Nottinghamshire in 1841. Upon the death of his father in 1853, he returned to Nottingham from a London boarding school and after finishing education, subsequently interned for the architect Sir Arthur Blomfield. Blomfield had been a friend of his deceased father and Fothergill interned for him prior to the construction of Blomfield’s Gothic masterpiece, The Royal College of Music. In 1864, Fothergill established his own practice at Clinton Street, but his offices were destroyed by the construction of the Great Central & Great Northern Railway’s Victoria Station (architect A. E. Lambert, demolished 1967). Fothergill constructed new offices on George Street at No.s 15-17. This work, emblematic of a matured Fothergill, bears the hallmarks of his idiosyncratic style: the ramshackle gable, the peculiar mixture of Old English Vernacular and the Gothic Revival, and the turreted towers which recall an idealised ‘Merrie England’ interpretation of the medieval period. Fothergill’s architecture was informed by the wider Gothic Revival in England, especially the works of George Gilbert Scott and George Edmund Street. This is apparent in the exterior of Fothergill’s Offices, with statuary adorning the façade echoing his inspirations, Augustus Pugin, Scott and Street. A curious representation of a medieval architect rests between these, perhaps Fothergill applying artistic licence to a representation and attempting to affiliate himself within a pantheon of his heroes.

The Context

Previously, Nottingham’s preeminent provincial architect was Thomas Chambers Hine, who developed an Italianate architecture indicative of the inspiration the upper classes derived from their ‘Grand Tours’ of the continent. Hine was most notable for his employment by the Clinton family, Dukes of Newcastle, who allowed him to develop the preliminary stages and designs for the Park Estate, which Fothergill also later worked on. The Park Estate was developed on the former parkland of Nottingham Castle, which had been torched by rioters due to the Tory Duke of Newcastle’s opposition to the Earl Grey and the Whigs’ Great Reform Act of 1832. By the 1860s, Nottingham shifted away from the Italianate architecture of the 1850s towards a Gothic style. Even Hine, who pioneered the Italianate aesthetic in Nottingham with his Adams Building (1855), Birkin Building (1855) and Corn Exchange (1850), shifted towards the Gothic, with his designs for the Baroque ruins of Nottingham Castle proposing a stolid tower placed atop the palace below. This arguably parallels the ‘Victorian Restoration’ of churches towards a fantastical appearance, evident in the works of Street and Scott: an approach which Fothergill would later embrace. Arguably, Fothergill’s works characterise the vernacular of Nottingham to the same extent of Brodrick in Leeds or Waterhouse in Manchester. In developing this local aesthetic, Fothergill came to define the appearance of Nottingham as the ‘Queen of The Midlands.’ The city blossomed as it shifted away from artisanal industries such as framework knitting towards mass production, evident in the lace firms of Adams and Birkin. Nottingham’s architecture conveyed the patronage of its local industrialists towards their communities: Adams’ building, for example, had a workers’ chapel and the provision of tea rooms. Nottingham’s progressivism was evident in the amenities provided by local manufacturers, such as the Theatre Royal which was commissioned by the Lambert brothers, who owned a lace firm.

Fothergill equally contributed towards this with his Temperance Hall (later Albert Hall, 1876) funded by private subscription and dedicated to the arts. He considered this his first major commission though his style soon shifted, Darren Turner noting his Bank at Pelham Street as his last work in the ‘High Victorian’ style, (and last ‘major’ work until the 1890s, with his Black Boy Hotel and Queen’s Chambers occurring thereafter). Fothergill’s career largely ceased during the 1880s, but by the 12th July 1890 he wrote, ‘This is the height,’ indicative of the resurgence of his reputation and the increased number of his works. It is this period, with his focus on a combination of Old English Vernacular and his Gothicism, that marks Fothergill’s apotheosis, a career renaissance after a dispiriting comment he made in 1887 at Lincoln Cathedral: ‘’The Gothic style is out of fashion (…) they have so far failed to produce new equal to the old.’ Fothergill’s dismissiveness both to others and his own earlier works symbolises a maturation to a refined approach with a more fantastical interpretation, noting in the same speech ‘they will return to this style, no other furnishes such an exhaustive mine of novelties.’ Fothergill’s reinvigoration led to a period of major projects which have since solidified his reputation.

The Symbolism

Fothergill’s architecture is unique to Nottingham, its eclecticism described as ‘idiosyncratic’ by Nikolaus Pevsner. The embellishments on his buildings are representative of the ‘novelties’ he described. These included polychromatic patterns of blue and red brick, informed by Ruskinian ideals in 1849’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture, written by Ruskin and influenced by his belief of Gothicism being ‘truer’ in comparison to the classicism of the Georgian era. Fothergill employed at times idiosyncratic details on his structures, such as the representation of a monkey referring to the burden of a mortgage on the Nottingham & Notts. Bank on Pelham Street (the Victorians used the term ‘stone monkey’ to refer to this,) or his use of friezes and reliefs on the Furley & Co. building of 1896. This was built for ‘provision merchants’ and depicts the stages of sugar harvest. Political symbolism is also evident in Fothergill’s Express Chambers (1876), with depictions of Liberal politicians such asWilliam Gladstone carved into the façade of the headquarters to symbolise the newspapers partisanship. Fothergill’s commissions also represent his interests, with designs for two coffee palaces and the Temperance Hall showcasing his opposition to alcohol. Ornamentation is sparser on Fothergill’s later structures as he moved away from the ‘High Victorian,’ but the distinguishing characteristics of his work remained unchanged. Turner notes how Fothergill’s work was unfashionable even during his era, as aside from significant national architects such as Scott or Waterhouse, provincial architects were left to shape the cities in which they practiced and were less respected than their national contemporaries. In 1897, ‘The Builder’ Magazine of London described his work as ‘florid’ and noted that ‘Gothic influence dies hard in Nottingham.’ Fothergill entered his ‘twilight’ by the mid-1890s. Semi-retired by 1901, his later work is subdued and sober: potentially the influence of his partner, Lawrence G. Summers, whose solo works are more restrained, or perhaps due to a move towards new Edwardian ideals of classicism, evident in the works of Lutyens and the ‘Edwardian Baroque.’ Fothergill’s later projects parallel Summers’. Described as ‘less didactic’ and practicing more restraint than even those during the 1880s prior to ‘the height,’ they represent a maturation toward an architect nearing the end of his practice.

Attributes & Ideals

Contemporary attitudes to Fothergill’s works shifted as the merciless march of progress saw his works derided as increasingly antiquated. In the first edition of Pevsner’s ‘Nottinghamshire’ (1951), Fothergill has two fleeting references, one describing the Nottingham & Nottinghamshire Bank at Newark as possessing a tower ‘too high to blend with the street,’ and the other describing the bank at Pelham Street as ‘civilised.’ Pevsner’s dismissive attitude towards Gothic architecture is apparent in his description of other Gothic buildings nearby as ‘fanciful ignorance.’ Fothergill’s work received a reprieve after the loss of his Black Boy Hotel, erected 1886-1900 and described by Andy Smart in the Nottingham Evening Post in 2017 as ‘one of Nottingham’s favourite lost buildings.’ This critical reappraisal has since seen Fothergill’s work framed as central to the character of the city, including the introduction of guided tours of his works and the publication by Brand (1997) of an introduction to his works and Turner’s (2012) catalogue raisonnè on Fothergill’s works.

Reinterpretation

Prior to this, Fothergill’s works occupied an uncertain location, unlike the assuredness which preposses their positions within the city. The conservation movement began in earnest with the formation of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877, but Fothergill’s fanciful Gothicism fell from favour as it lacked the antiquarian interest that SPAB focused on. SPAB, established by William Morris of the Arts & Crafts movement which focused on realism, was founded as a reaction against Scott’s approach of ‘Victorian Restoration’ to churches that focused on aesthetics over accuracy. As such, Fothergill’s mythic architecture was the antithesis of SPAB’s understanding of the past as being based on antiquity, and antithetical to their interests which focused on medieval structures.

Fothergill’s works, such as the demolition of the historic fabric of The Black Boy (which dated to the seventeenth th century) to be replaced with his idealistic interpretation removed the antiquarian interest, establishing a Victorian understanding of the medieval. As such, a lack of historic preservation societies, with the listing system only being established in 1947, with previous protections only applying to ‘Scheduled Monuments’ due to legislation campaigned for by SPAB, and passed in 1882. Coupled with the contemporaneous distaste of the Victorians, and the manifestation of a new, post war Britain of Brutalism, Fothergill’s works fell out of favour. As such, his works were overlooked in favour of other structures. Even with the passing of the Town & Country Planning Act of 1947, the first of Fothergill’s works were not listed until 1972, after the loss of the Black Boy Hotel (1970.) As such, Fothergill’s works occupied a precarious position, arguably until groups such as Betjeman’s Victorian Society started leading high profile national campaigns for the preservation of the nation’s urban heritage. Examples include the preservation of St. Pancras Station, Scott’s masterpiece, the failed campaign to preserve the Euston Arch (1837 – 1962) and the V&A’s exhibition ‘The Destruction of the Country House’ (1974), heritage conservation was not at the forefront of public or private interest.

Commenting on this, Gavin Stamp notes in 2010 that ‘the whole Victorian age came to be seen as dark and oppressive,’ noting that even the satirist P. G. Wodehouse wrote, ‘whatever can be said of the Victorians (…) few were to be trusted with a pile of bricks.’ This acrimony towards a prior age is evident as early as the Edwardian period, and parallels the Victorians’ dismissiveness of the Georgians. Herbert Baker’s mutilation of Soane’s Bank of England is regarded by Nikolaus Pevsner, as nothing short of a travesty and yet modernity remained central over the preservation of heritage. This underlying contempt for the past later led to the wider preservation movement. Eventually, a shift in focus from urban renewal towards restoration offered a reprieve to Fothergill’s works, with buildings either being restored (such as Queen’s Chambers) or rehabilitated, such as the retention of the façade of the Jessop Building (1895). By August 1974, Nottingham’s planning committee wrote to readers of a local newspaper: ‘May I reassure your readers… the national and local value will not be overlooked.’ In 1975, an article noted that it would be unlikely to see the demolition of Fothergill’s Express Chambers permitted and unthinkable to see such public belief in posterity after the demolition of the Black Boy just five years prior. However, Fothergill’s losses continued into the 1980s. Turner notes that in 2012, the latest loss occurred just a year prior: a previously unattributed factory in Lenton.

An Ending

Fothergill died in 1928 and is buried at Nottingham’s Rock Cemetery. His grave is indistinct in contrast to the excess of his works. A simple granite stump and a gilt Gothic script is an understated tribute to a man who shaped the Nottingham of the late Victorian Era to the same extent as T. C. Hine before him. Upon his death, the Nottingham Journal noted that ‘Nottingham has lost one of its most distinguished (…) it may be said that no man has left his mark in the character of buildings to the same extent.’ Fothergill’s work, once unfashionable, has now reasserted itself as a defining feature of Nottingham’s cityscape and his immeasurable contribution, means that Fothergill remains within the collective conscience of the city. His invariable effect on defining the character, and creating a sense of place within Nottingham means he remains within a pantheon of provincial architects, alongside Hine and Howitt as responsible for the urban fabric of the city. Fothergill’s works are now heralded, though his Black Boy Hotel remains the work to which he is most associated, Turner declared the Black Boy Hotel a ‘martyr,’ as it allowed for a retrospective reinterpretation of Fothergill’s works.

Written by Tyler Arnold

Bibliography:

Fig. 1 – A picture of Mr. Fothergill ca. 1880. (Main Image.) https://www.watsonfothergill.co.uk

Fig. 2 – Mr. Fothergill’s Offices, George St. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Watson_Fothergills_Offices_at_15_George_Street_in_Nottingham.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

Fig. 3. – The Black Boy Hotel, 1939. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black_Boy_Hotel.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

Fig. 4. – Detailing at Fothergill’s Offices. Note the characteristics, such as polychromatic brickwork, Gothic plaques, and use of local sandstone and Fothergill’s habit of carving his name. https://www.visit-nottinghamshire.co.uk/things-to-do/watson-fothergill-head-office-p625931

Fig. 5. – Fothergill’s simplistic grave. https://nottinghamhiddenhistoryteam.wordpress.com/2013/02/14/nottingham-famous-graves-watson-fothergill

Brand, K. (1997) Watson Fothergill, Architect. Nottingham: Nottingham Civic Society.Historic England (2017) The buildings of architect Watson Fothergill.

The Historic England Blog, 13 February. Available at: https://heritagecalling.com/2025/02/13/the-buildings-of-architect-watson-fothergill/ (Accessed: 30th May, 2025).

Nottingham World (2025) Clever meaning behind Nottingham monkey sculpture, 25 June. Available at: https://www.nottinghamworld.com/news/clever-meaning-nottingham-monkey-sculpture-4699590 (Accessed: 30th May, 2025).

Pevsner, N. (1951) The buildings of England: Nottinghamshire. Middlesex: Penguin.

The Design Review Panel (2017) In praise of Fothergill Watson, 30 March. Available at: https://www.designreviewpanel.co.uk/post/2017/03/30/in-praise-of-fothergill-watson (Accessed: 29th May, 2025).

Turner, D. (2012) Fothergill: A catalogue of the works of Watson Fothergill, architect. Nottingham: The Darren Turner Partnership.

Watson Fothergill (n.d.) Available at: https://www.watsonfothergill.co.uk (Accessed: 28th May, 2025).

British Listed Buildings 15 & 17 George Street. Available at: https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101247548-15-and-17-george-street-bridge-ward (Accessed: 27th May, 2025).