“Make all the Railways come to York”- a brief history of the railway industry in York

Since the Romans founded the city in 71 CE, the position of York in the flatlands of the Vale of Yorkshire has ensured the city has been a centre for transportation throughout its existence. Yet arguably the most significant aspect of York’s transportation heritage is its importance as a railway nucleus, a position it has maintained from the mid-19th century to the present day. York’s importance in the railway network of Great Britain is only matched by the significance of the railways to York’s development, and it is no exaggeration to say that had the railways not come to York, the city as we know it today would hardly exist. As such, this article provides a brief overview of how all the railways came to York, and the effects this had on the lives of the city’s residents.

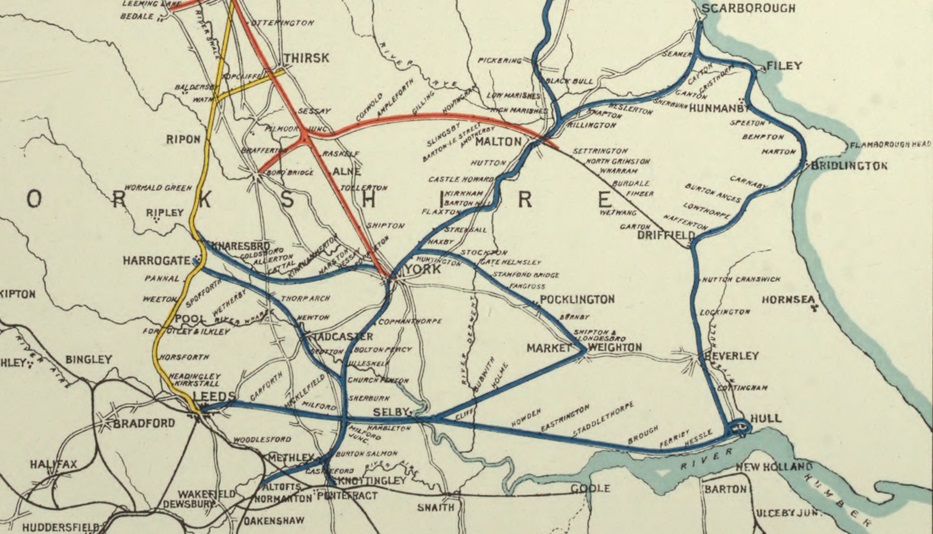

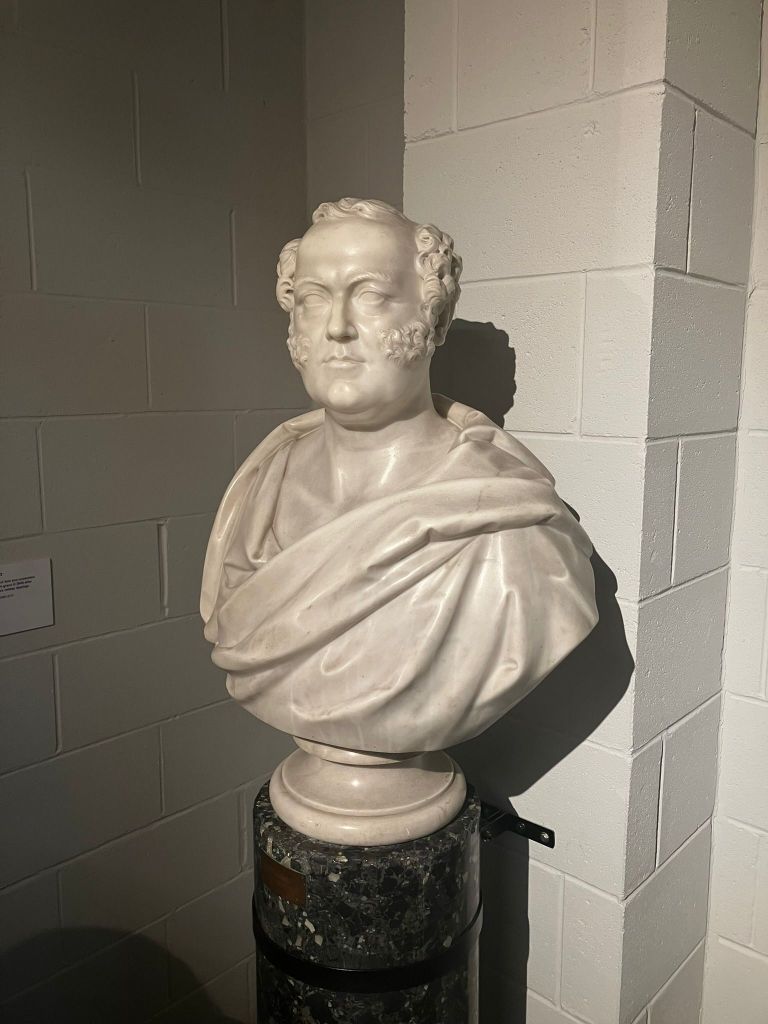

Following the opening of railway pioneer George Stephenson’s Stockton and Darlington and Liverpool and Manchester railways in 1825 and 1830 respectively, the railways quickly became an integral feature of the rapid industrialisation engulfing Britain during the early 19th century, with booming industrial cities such as Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham and Newcastle all being welded together as engineers and workers rapidly connected them with ribbons of steel. In contrast to this rapid industrial development, York, once the mighty Capital of the North, appeared to be falling behind. It boasted very little industry, manufacturing, and finance; its economy instead centred on the building, leather, and transport industries. In the face of this impending decline, one man emerged with an apparent solution– George Hudson, Lord Mayor of York, who believed the city’s fortunes could be reversed if it embraced the railways. Although he likely never said these words, Hudson’s goal was to “make all the railways come to York.” Hudson, himself a close friend of Stephenson, formed the York and North Midland Railway (Y&NMR) in 1835, which in 1839 had built York’s first railway to Normanton, near Wakefield, linking with the Leeds and Selby Line; by 1840, through connections to the Midland Railway, it was possible to reach London by train, a journey of fourteen hours. York’s flat landscape and geographical location meant it lay in the centre of numerous vital railway corridors. The main line from London to Edinburgh passed through the city, as did the east-west link from Hull to Liverpool via Leeds and Manchester. The construction of new lines to Harrogate, Church Fenton, and Scarborough meant that, very quickly, Hudson’s dream of a York that formed the centre of Britain’s developing railway network was being realised. In doing so, this set York apart from Britain’s other ancient cities, which generally ferociously opposed the coming of the railways– Cambridge Station, for example, was built far outside the city centre, as the university wished to have nothing to do with the new industry. This stands in stark contrast to York, where even the venerable ancient walls were cut through in order to bring the original station as close as possible to the city centre.

Hudson himself had ambitions that went far beyond his native city. In 1844, he convinced the shareholders of various struggling railway companies in the north to amalgamate into one, the Midland Railway, of which he became chairman, running the company from his headquarters in Derby. A ruthless businessman, Hudson quickly became the figurehead of the “Railway Mania” of the 1840s, where speculative investment poured into proposals for new railways. His network, which was just 30 miles long in 1839, had expanded to 1,450 miles ten years later, stretching from Norwich to Bristol to Edinburgh. At the height of his power, Hudson’s empire accounted for half the railways in Britain, and he was soon granted the sobriquet of “the Railway King”. Aside from his mayoralship in York, he also became MP for Sunderland, and grew immensely wealthy. It was soon revealed, however, that his wealth was built on the back of fraud. When paying out dividends, Hudson would give shareholders speculative capital rather than actual revenue, meaning once speculation ended, they became worthless. His subsequent downfall was a national sensation, with Hudson eventually fleeing the country to avoid prosecution. In York, the city that once loved him turned its back on him, with Hudson Street near the station being renamed to Railway Street, only regaining its original title in 1971. A pub once named after him on that street now hosts the Popworld nightclub; whether this is an appropriate legacy for the once-mighty Railway King is left to the discretion of the reader.

Of course, it was not just Hudson that embraced the railways in York. The opening of the Y&NMR in 1839 was declared a public holiday, accompanied by large celebrating crowds and the ringing of the Minster bells, demonstrating that the railways were welcomed by everyday residents of York just as much as its politicians. Over the subsequent decades, the railways would have a profound effect on York’s social life, most evident in the changes in the city’s industry. The arrival of the railways turned York into a centre for manufacturing, in particular light industry, including flour-milling, printing, and glass-making, as well as the manufacture of chemicals, scientific instruments and– most famously– chocolate making. One consequence of this development was the increase in immigration to York throughout the 19th century. Previously, the city had little to offer to immigrants, but the arrival of the railways brought more money and employment to it, contributing to a dramatic population increase- from 16,000 in 1801 to 70,000 by 1900. As noted by Seebohm Rowntree in his groundbreaking 1899 study of poverty in York, many of these workmen were Irish, fleeing the Great Famine of 1845-49. Their arrival amongst others helped to foster the growth of suburbs in Fulford, Clifton and Holgate, expanding the size of the city. This population growth also had a substantial effect on the city’s architecture and infrastructure, as increased road traffic resulted in the construction of new buildings and bridges across the Ouse; this included Lendal Bridge, which ended the Ouse Bridge’s centuries-old monopoly on river crossings.

In 1854, Hudson’s York and North Midland had amalgamated with other companies into the North Eastern Railway (NER), which ran services across the North East but had its headquarters and manufacturing located in York. As a result of this, the railways themselves quickly became the city’s largest employer, a continuation of its legacy as a centre of transportation. The coaching industry in York was once one of the largest in the country, employing hundreds of workers in coaching inns, maintenance of the stagecoaches and care of the horses; all this was rendered obsolete by the railways, as was water navigation and transportation upon the River Ouse. York grew not just as a railway hub, but as a centre for the building and maintenance of locomotives and carriages. In 1841, the railways employed just 41 workers, which increased to 513 by 1851, 1,200 by 1855 and to 5,500 by 1900. Alongside the chocolate industry, the railways dominated York’s labour market, accounting for a quarter of all employment and half of manufacturing jobs. The carriage works, first located on Queen Street and later in Holgate, made York a hub for construction and maintenance of rolling stock throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, with its workshops, engine sheds and foundries accounting for over half of the railway employment in the city; over the course of the 20th century, many of the units that still operate on the network today would be constructed at York, with this manufacturing only ceasing when the works closed in 2002.

An analysis of Rownstree’s aforementioned 1899 study, which divided York’s working class into different categories of income, shows that most railway households earned around 30 shillings per week– better than many other professions, but by no means affluent. However, working on the railways had its perks- In 1855, the NER opened the York Railway Station Library and Reading Room, intended for the benefit of railwaymen and youths working for the company, as well as to foster their intellectual, social and moral well-being. During the winter, this was accompanied by seasonal lectures on a number of topics, predating the lectures at the university by more than a century. Come the holiday season, the NER would provide cheap day and half-day excursions to seaside resorts such as Scarborough, which were highly popular amongst the working class; generally, rail travel was more usual amongst workers in York than elsewhere in the country, as the railwaymen had access to cheaper “privilege tickets” that made travelling more affordable.

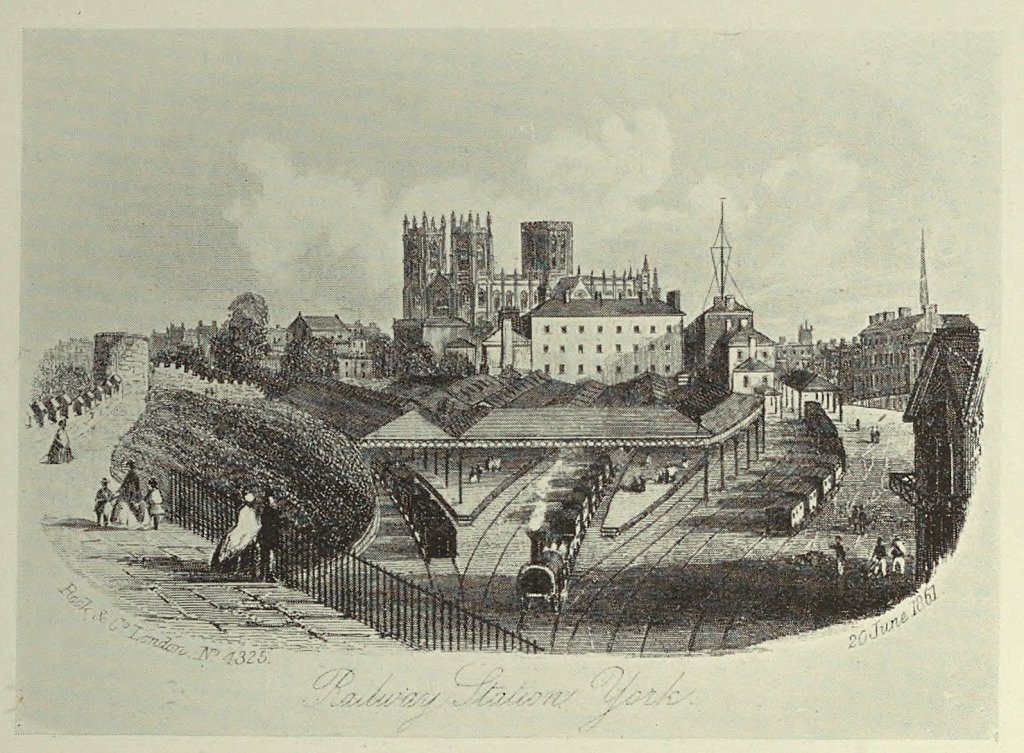

But whilst the carriageworks and engine sheds of York formed the bedrock of employment in the city throughout the 19th and early 20th Centuries, it was York’s stations that connected it to the rest of the country, truly making it the epicentre of Britain’s railways. The plural form of “station” used above is not a mistake- over the course of its history, York has hosted three railway stations, each larger and grander than the last. When the line to Normanton was first built, the York and North Midland Railway had yet to punch through the ancient city walls, necessitating the construction of a temporary wooden station by Queen Street.

It wasn’t until 1841 that the tracks were brought through the walls to a new location on Tanner Row, near Micklegate; the ability to carve an archway for the trains through the walls was only enabled through Hudson’s position as Lord Mayor. The station was built in Italianate style, with a cast-iron and glass roof for the main shed. The part of the city it was built in experienced substantial regeneration and transformation following the station’s arrival. However, despite enlargement over the following years, the building was inadequate due to its layout as a terminus station– any train travelling through York would have to reverse to continue its journey, which caused considerable delay. By the 1870s, the station lacked the capacity to handle the growing amount of traffic, prompting the construction of a new station outside the city walls. By 1877, construction was complete on the new York station, still in operation today. Its location on a curve in the line was superbly utilised by its grand, crescent-shaped roof, 800 feet long and 234 feet wide, establishing the station as the largest in the world upon opening. Ever since its opening, York’s position on the premier East Coast Main Line has made it a vital stop for Anglo-Scottish expresses, as well as a hub for local and regional services; even today, very few services bypass York entirely. For any other city with a relatively low population comparable to York’s, this would seem strange; yet, for this city, its importance makes sense. York is not a railway centre because of any particular industry or population size, but because it chose to become a railway centre. The city retains its importance to the present day because, almost 200 years later and as per the desires of Hudson and his city, all the railways still come to York.

The arrival and evolution of the railways in York transformed the city and its population in immeasurable ways, facilitating its population growth and the development of its industries, as well as permanently altering its demographics, social life, infrastructure and architecture. The York we know today would not have existed without the coming of the railways. Indeed, it is likely that this university, and this publication, would never have existed either. The York and North Midland and North Eastern Railways are gone; the old station was demolished in 1966 and the carriage works closed in 2002, but York remains a railway epicentre. In the 21st century, it can still be said that all the railways come to York, for the benefit of the city, its population and its history.

Written by Oscar Hilder

Bibliography:

Appleby, Ken. York. Shepperton: Ian Allan, 1993.

Booth, R. K, and provenance York City Art Gallery. York : The History and Heritage of a City. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1990.

Brockbank, James Lindow, and W M Holmes. York in English History; London, etc: A. Brown, 1909.

Evans, Eric J. The Forging of the Modern State : Early Industrial Britain, 1783-1870. 3rd ed. Harlow: Longman, 2001.

Evans, R. J. The Victorian Age, 1815-1914. London: Arnold, 1950.

Feinstein, C. H. “Population, Occupations and Economic Development, 1831-1981.” In York 1831-1981 : 150 Years of Scientific Endeavour and Social Change, edited by Charles Feinstein, 109-159. York: Sessions, 1981.

Harvey, John, and Raymond Burton. York. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1975.

Knight, Charles Brunton, Cyril Garbett, and J. A. R Marriott. A History of the City of York; from the Foundation of the Roman Fortress of Eboracum, A.D.71, to the Close of the Reign of Queen Victoria, A.D. 1901. York: Herald, 1944.

Nuttgens, Patrick, and John Shannon. York: The Continuing City; 2nd ed. York: Maxiprint, 1989.

Rodgers, John. York. London ; Batsford, 1951.

Rothnie, Niall, and Mazal Holocaust Collection. The Baedeker Blitz : Hitler’s Attack on Britain’s Historic Cities. Shepperton: Ian Allan, 1992.

Rowntree, B. Seebohm, and C. H Feinstein. Poverty : A Study of Town Life. London: Macmillan and co., limited, 1901.

Royle, Edward, Stephen Copley, Norman Hampson, and J. A Sharpe. Modern Britain : A Social History, 1750-1985. London ; E. Arnold, 1987.

Brooks, F.W. “York- 1066 to Present Day.” In The Noble City of York, edited by Alberic Stacpoole and Raymond Burton. York: Cerialis Press, 1972.

Tomlinson, William Weaver. The North Eastern Railway: Its Rise and Development. (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Andrew Reid and Company, Limited; London: Longmans, Green and Company; 1915.) 350, plate XVII. Accessed June 24th, 2025. https://archive.org/details/northeasternrail00tomlrich/northeasternrail00tomlrich/mode/2up

Tomlinson, William Weaver. The North Eastern Railway: Its Rise and Development. (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Andrew Reid and Company, Limited; London: Longmans, Green and Company; 1915.) 524, plate XXX. Accessed June 24th, 2025. https://archive.org/details/northeasternrail00tomlrich/northeasternrail00tomlrich/mode/2up

Wenham, Leslie Peter, Douglas Phillips, and Barbara Hutton. York. Harlow: Longman, 1971.

Whellan, T, Charles Louis Farret, William Wade, Raymond Burton, and Provenance Sessions Book Trust. History and Topography of the City of York and the North Riding of Yorkshire; Embracing a General Review of the Early History of Great Britain, and a General History and Description of the County of York. Beverley: Printed for the publishers, by John Green, 1857.

Willis, Ronald. Portrait of York. London: Robert Hale, 1972.

Wilson, Van C. M, and York Archaeological Trust. Rations, Raids and Romance : York in the Second World War. York: York Archaeological Trust, 2008.