The Victorian “Poison Panic”: Was Poison Really the Problem?

The Victorian Era was no stranger to poison: with arsenic in cosmetics, cyanide in the wallpaper, and strychnine as a form of pest control. It is a miracle anyone survived with the poison exposure they dealt with day-to-day. Despite this constant contact, a ‘poison panic’ emerged in Victorian media specifically at the time of the Essex poisoning trials from 1846-1851 (which involved three women: Sarah Chesham, Mary May, and Hannah Southgate, who were all suspected of poisoning their husbands). Although these trials are associated with the ‘poison panic,’ the panic was not limited to these three women. This article aims to analyse if public fear stemmed from the threat of poison itself, or rather the threat of female power. In order to do this I carried out a mini-study which included the cases of twenty-two women across the period 1752-1889. The women involved were all mentioned in the historical works I have referenced, but I drew my own conclusions by comparing them all.

In the nineteenth century, women had become secondary citizens, expected to stay home and create a loving space while their husbands went off to work. Although they did have less of a role in employment in this period, that is not to say that they did not help with certain jobs like bookkeeping or interacting with customers in shops, alongside domestic chores. Lower class, and some middle-class women, had to work to live but this was against the ideal female standard, and only one third of women were employed at any given time. Women were expected to marry and have children as the ‘ultimate goal,’ while conforming to strict rules of modesty and refinement that upheld the image of innocence and dutifulness. This notion is reflected in the English poet Coventry Patmore’s 1854 book Angel in the House. Not only was their education dismissed, in favour of male intelligence, but it was also in this period that fashion began to sexualise their bodies more, with corsets emphasising the hips and breasts. Men and women were expected to stay in their ‘separate spheres,’ suggesting a sense of protection for female ‘angelicness,’ yet societal reactions to women pushing these boundaries makes us question if the spheres were enforced to protect them in society or protect others in society from them.

The Line between Botany and Poison

Botany and the ideals of the female sphere go hand-in-hand, allowing them to understand the natural world to prepare for domestic responsibilities and form a sound mind. Although there is not much documentation of female botanists, it is said that the Enlightenment led to them having a role in this field of study, specifically creating illustrations, like Anne Pratt. The caring of plants was seen as comparable to the caring of children and was believed to produce patience and observational skills in a woman. However, if botany allowed women to pay attention to the natural world in an acceptable way that reflected their duties, poisonous plants were the villainous twin that corrupted women… afterall, Belladonna is a plant, but it is also poisonous, so where did they draw the line?

Admittedly, however, Belladonna was not a common poison reported in poisoning trials: substances like arsenic, strychnine, or chloroform were the repeat offenders. Arguably, this is where the real distinction between botany and poison can be seen: substances versus plants. Although, these substances were just as common in the household as a child would have been. They were easily attainable from shops, sold as medicines, pesticides, or in other products for many years, and attempts to regulate substances were largely unsuccessful. For example, the 1851 Arsenic Act only focused on arsenic, meaning poisoners could still use other substances, and other anti-poison bills were cancelled or put off. These substances became so ingrained in domestic life that it could be said that poisons were more common than plants – maybe a woman’s interest in poison was a way of them understanding the ‘natural’ world they had been forced to live in. Of course, not all women bought poison with intent of killing, but, then again, not all those convicted had the intention of it either.

Dangerous drugs and classic poisons were still easily available until the 1920s/1930s, meaning people could accidentally die of poison, or use it to cause self-inflicted deaths with relative ease. A summary on poison-related deaths, from 1837-1838 in England and Wales by the House of Commons, suggests that, in 1839, only nine out of 445 cases (with an immediate cause of death) were from murder, the rest being suicide or accidental. This report corroborates with that of Alexander Wynter Blyth, esteemed chemist and toxicologist, whose report included cases in England and Wales during 1883-1892. Blyth claims only forty-two of 6,616 people who ingested poison were murdered, highlighting the rarity of purposeful poisoning.

Since poisoning symptoms were similar to those of influenza, and murders of this type tended to be premeditated, people feared murders could be going undetected which created a lot of panic. However, the invention of the Marsh Test (an arsenic detection test) in 1836 gave some comfort to the truth being revealed eventually. In fact, the nineteenth century brought around the start of modern toxicology forensics. However, as mentioned above, the regular contact could mean traces were found in the blood, despite no foul-play. The bloodless approach of poisoning made it a perfect weapon for women, but it also needed to be done tactfully. The relative ease to acquire substances made men wary of the domestic home, especially as more cases were reported on, and ultimately an image of women causing chaos in the home emerged. It is an interesting evaluation: that passive, uneducated women, who could only be nurturers in the eyes of most men, were believed to have the ability to carry out such a calculated attempt of regaining their agency.

Poisonous Women

The use of poison reinforced the deceptiveness of women, who were made to conceal their true selves to fit society’s image. James Whorton, a professor of the history of medicine, estimates that 55% of female killers used poison. On the other hand, American science journalist, Deborah Blum, claims poison played the part of an “equalizer” in society. She suggests that it allowed women to kill without strength and violence (though this is not to say women did not kill violently like Eliza Gibbons who shot her husband in the head in 1857), especially as many females killed in an attempt to leave an abusive partnership. Although this was not always the case, examples of women killing due to romantic rivalry or adultery emphasised the believed characteristics of their jealousy, greed, and hysterical tendencies. This can be seen in the cases of Mary Bateman (The Yorkshire Witch, accused of poisoning a woman named Rebecca Perigo who came to her for help with medical ailments) or Christiana Edmunds (The Chocolate Cream Killer, who laced sweets with strychnine).

Women should not have been a risk to men. The punishments received by women poisoners seemed to act as a deterrent for others: Sarah Chesham and Mary May of the Essex poison trials were both hanged. Between 1830-1900, compared to a 40% conviction rate for general murder cases, women convicted of poisoning their husbands was at 60%. The shift of preference from incarceration/execution to an insanity conviction later in the period is said to have been observed by Martin Wiener, American history academic. However, out of the twenty-two women I looked at, this trend does not correlate. During 1752-1889, sixteen out of the twenty-two women were initially sentenced to death, but only four were changed to exile/life imprisonment, and five were not charged (the remaining woman was sentenced to life). Despite evidence proving that female poisoners were either uncommon or harshly judged, in the context of women fighting for agency, strong reactions against these crimes suggest the problem laid elsewhere.

“Mary Ann Cotton, she’s dead and she’s rotten, lying in bed with her eyes wide open.

Sing, sing. What song should I sing? Mary Ann Cotton is tied up with string.

Where? Where? She’s up in the air, and they’re selling puddings for a penny pair.”

(A satirical poem found under wallpaper in a Victorian Terrace in 2016, written about Mary Ann Cotton, considered the world’s most renowned arsenic murderess by Deborah Blum.)

Fuelling the Panic

The media played a huge role in the escalation of this panic, influencing the public by documenting poison trials and, in the 1840/50s, most women were executed for poison crimes. Newspapers represented them as unstable and focused on how their behaviour fitted into societal ideals (or, rather, how they did not), rather than evidence. This implies that their compliance to their sphere was more important than actually committing the crime. Despite commenting on these crimes to cause a panic and prevent it, there is also a theory that sensationalist journalism facilitated this act: publishing details of these crimes could have led to more people being informed and able to poison themselves. Media equally had a positive effect in helping some cases, like that of Charlotte Harris. Public protests and petitions led to her death sentence being changed into being transported to colonies due to her pregnancy. Around the same time, another pregnant woman was sentenced to death, deemed not-pregnant by a jury of matrons, but gave birth in prison. These cases indicate how pregnancies could affect public support.

It was not just newspapers but also literature that played a role in the panic, and authors like Mary Elizabeth Braddon found themselves metaphorically on trial due to the belief that their work influenced women to commit poisonings. In the real-life case of Madeleine Smith, accused of killing Emile L’Angelier, the fact she had written letters to two men proved she was not innocent in the eyes of the court as she went against female ideals. However, this lack of femininity seemed to imply she had been a victim of corruption, either by L’Angelier or literature, as she was seen attending a performance of Lucrezia Borgia (an Italian noblewoman rumoured to have poisoned rivals) before L’Angelier was found dead – the court concluded “not proven.”

The Rise of Feminism

Some publications and legislations on the advancement of women’s rights occurred before the Victorian Era, for example Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), however it was the reign of Victoria that saw the official arrival of the first feminist wave. It was not until 1839 that the Custody of Infants Act, the first act giving women more rights, appeared. The following decade saw the Seneca Falls Convention (the first woman’s rights convention in the United States pivotal for the movement towards women’s suffrage), where no doubt ideas would have spread further afield, and the fight for women’s rights in votes, education, and property increased. Again, using the twenty-two women I looked at who were accused of poisoning, nineteen of them occurred after 1839, and twelve after 1848. Thus, it seems that women were more likely accused after feminism’s first wave had affirmably started, although I did not look at poisonings from before the Victorian Era. Queen Victoria herself described the feminist movement as a “mad wicked folly,” due to her conservative and liberal political views, but she did fight for women’s education, opening girl-only colleges. Queen Victoria was not an antifeminist, she just did not welcome radical changes.

Across this period, many associations, acts, and publications appeared to show the change of women’s ideas on their place in society – some more radical, others more practical. For example, in 1847, Anne Knight founded the Female Political Association, and 1897 saw the establishment of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society (NUWSS). Of course, my study only covered a small selection of women over a specific period of time, however the trends of when women were convicted for poisoning and their punishments seems to somewhat coincide with an increase of female political force. Especially when other statistics imply that poisoning with the intent of killing was not that common, and that women were more likely to be tried for murdering their partners than men. It also seems that the media and journalism, no doubt controlled by men, fuelled this panic out of proportion.

The Poisons Act was not passed until 1972, over 100 years after the ‘panic’ occurred, insinuating that the problem was not the poison itself but rather the threat of women gaining agency. These conclusions seem to point in the direction that it was the evolution of how women saw themselves in society, and a fear of them gaining power and rights, that was the problem, but the threat of poisoning was used as a scape-goat.

Written by Finlay Ratcliffe

Bibliography

Photos:

An unscrupulous chemist selling a child arsenic and laudanum. Wood engraving after J. Leech. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. April 7, 2025. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hcw9dhst.

Jacqueline Lambert. “Hemlock/Dropwort/Cow parsley.” World Wide Walkies. April 7, 2025. https://worldwidewalkies.blog/2020/06/28/poisonous-plants-which-may-be-common-in-your-back-yard/.

A Poem about serial killer Mary Ann Cotton via The Northern Echo. April 7, 2025.https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/14942289.poem-murderess-mary-ann-cotton-discovered-wallpaper-victorian-terrace/.

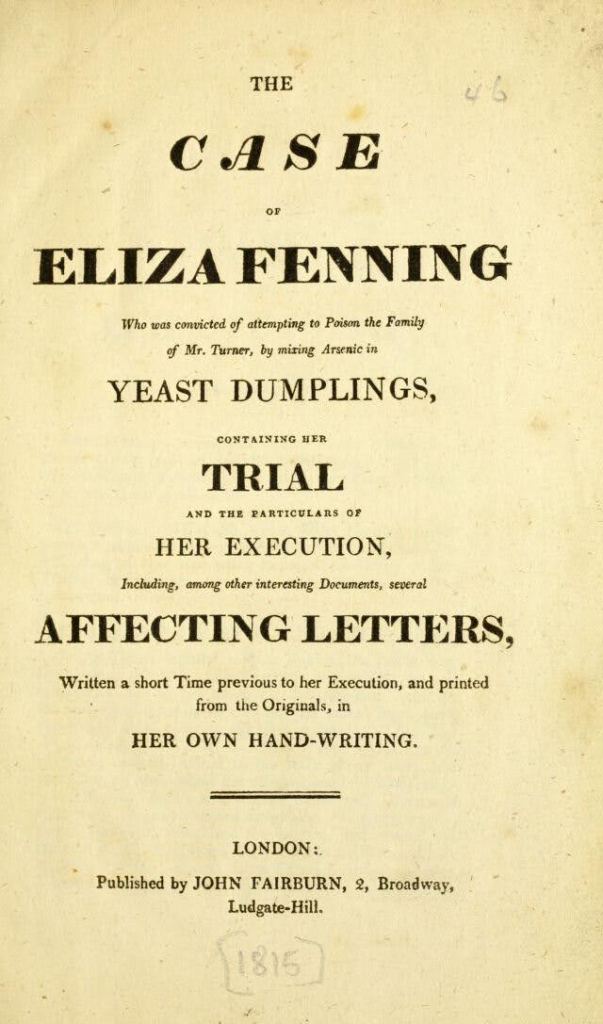

The case of Eliza Fenning who was convicted of attempting to poison the family of Mr. Turner by mixing arsenic in yeast dumplings : containing her trial, and the particulars of her execution, including … several affecting letters written a short time previous to her execution / [Anon]. Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection. April 7, 2025. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/djh6avuu.

London Remembers. “Queen’s College Plaque” via London Remembers. April 7, 2025. https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/queen-s-college.

Websites:

Abrams, Lynn. “Ideals of Womanhood in Victorian Britain” BBC. September 18, 2014. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/trail/victorian_britain/women_home/ideals_womanhood_01.shtml.

Armfield, Julia. “Arsenic, Cyanide and Strychnine – the Golden Age of Victorian Poisoners.” Untold Lives Blog. September 18, 2014. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2014/09/arsenic-cyanide-and-strychnine-the-golden-age-of-victorian-poisoners.html.

Knight, Shaneka. “The History of Feminism in the UK.” The Sociological Mail. October 1, 2018. Accessed March 24, 2025. https://thesociologicalmail.com/2018/10/01/the-history-of-feminism-in-the-uk/.

Mitchell, Tonya. “Lady Killers of the 19th Century: Women Who Poisoned (Part 1).” Tonya Mitchell Author. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.tonyamitchellauthor.com/post/lady-killers-of-the-19th-century-women-who-poisoned-part-1.

Mitchell, Tonya. “Lady Killers of the 19th Century: Women Who Poisoned (Part 2).” Tonya Mitchell Author. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.tonyamitchellauthor.com/post/lady-killers-of-the-19th-century-women-who-poisoned-part-2.

Parker, Shona. “Gender roles in the Victorian Era.” Back in the Day of. June 17, 2020. Accessed March 24, 2025. https://backinthedayof.co.uk/gender-roles-in-the-victorian-era.

University of St Andrews. “Venomous women of the 19th century.” University of St Andrews. February 19, 2009. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://news.st-andrews.ac.uk/archive/venomous-women-of-the-19th-century/.

Wikipedia. “Feminism in the United Kingdom.” Wikipedia. March 21, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism_in_the_United_Kingdom#:~:text=19th%20century,-Main%20article%3A%20History&text=The%20first%20organised%20movement%20for,employment%2C%20education%2C%20and%20marriage.

Newspapers:

Chloe. ”A Woman’s Place in Victorian Society – Social and Fashion.” Fashion-Era. October 13, 2024. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://fashion-era.com/fashion-history/victorians/victorian-era-women.

Cossar, Elena. “The Role Of Women In Victorian England.” Oxford Open Learning. February 1, 2021. Accessed March 21, 2025. htttps://www.ool.co.uk/blog/the-role-of-women-in-victorian-england/.

Goedluck, Lakeisha. “A Brief History of Women Putting Poison in Their Lovers’ Food.” Vice. October 5, 2015. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://www.vice.com/en/article/a-brief-history-of-women-putting-poison-in-their-lovers-food/.

Haggerty, Meredith. “That Girl Is Poison: A Brief, Incomplete History of Female Poisoners.” Medium. December 16, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://medium.com/the-hairpin/that-girl-is-poison-a-brief-incomplete-history-of-female-poisoners-f6f9aa32507d.

Mazzola, Anna. “When female ‘poisoners’ created a national moral panic.” Telegraph. March 5, 2024. Accessed March 21 2, 2025. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/authors/the-female-essex-poisoners-victorians-murder/.

Woodward, Afton Lorraine. “Plants, Domesticity, and the Female Poisoner.” The New Enquiry. November 17, 2026. Accessed March 24, 2025. https://thenewinquiry.com/blog/lady-science-no-26-lady-wrangler-and-poisoners/.

Secondary Literature:

Arthur, Rhonda. “Charlotte Harris ‘the orange woman’: per Anna Maria 1852.” Female Convicts. Accessed March 24, 2025. https://femaleconvicts.org.au/docs2/convicts/CharlotteHarris_AnnaMaria1852.pdf.

Bulamur, Ayşe Naz. Victorian Murderesses: The Politics of Female Violence. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

Helfield, Randa. “Poisonous Plots: Women Sensation Novelists and Murderesses of the Victorian Period.” Victorian Review 21, 2 (1995): 161-188.

Morton, Alison. “The Female Crime: Gender, Class and Female Criminality in Victorian Representations of Poisoning.” Midlands Historical Review 5, (2021): 1-24. https://www.midlandshistoricalreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/The-Female-Crime_-Gender-Class-and-Female-Criminality-in-Victorian-Representations-of-Poisoning.pdf.

Nagy, Victoria. (2013). “Narratives in the courtroom: Female poisoners in mid-nineteenth century England.” European Journal of Criminology 11, 2 (2013): 213-227. 10.1177/1477370813494841.

Nsaidzedze, Ignatius. “An Overview of Feminism in the Victorian Period [1832-1901].” American Research Journal of English and Literature 3, 1: 1-18.

Price, Cheryl Blake. “Poison, Sensation, and Secrets in ‘The Lifted Veil.’” Victorian Review 36, 1 (2010): 203–16.

Robb, George. “Circe in Crinoline: Domestic Poisonings in Victorian England.” Journal of Family History 22, 2 (1997): 176-190.

Shteir, Ann B. “Botany in the breakfast room: Women and early nineteenth-century British plant study,” In Uneasy careers and intimate lives: Women in science 1789–1979, edited by Abir-Am Pnina and Dorinda Outram. New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press: 1987.

Watson K. D. “Poisoning Crimes and Forensic Toxicology Since the 18th Century.” Academic forensic pathology 10, 1 (2020): 35–46.

Theses:

Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science. “Sensational Murders: A Poisonous History of Victorian Society.” Dartmouth Undergraduate Journal of Science. Accessed March 21, 2025. https://sites.dartmouth.edu/dujs/2008/02/21/sensational-murders-a-poisonous-history-of-victorian-society/.

Howard, Izzi, “Arsenic in Victorian Britain: A Primary Source Analysis” (2024). Student Scholarship. 252. https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/studentscholarship/252.

O’Hare, Sydney. ““Wilful” Women: Representations of Female Murderers in The London Times from 1805 to 1880.” Senior Theses, DePaul University, 2018. https://academics.depaul.edu/honors/curriculum/archives/Documents/2019%20Honors%20Senior%20Theses/Ohare,%20Wilful%20Women%20Representations%20of%20Female%20Murderers.pdf.

Vandepol, Ashley. “Depictions of a Poisoner: Examining Press Coverage of Female Poisoners as a Means of Investigating Changing Ideas of Women’s Character During 19th Century England.” Bachelor’s Dissertation, University of Victoria, 2022.