‘Stasiland’: Anna Funder’s Oral History Masterpiece

“And then it comes. I’m making portraits of people, East Germans, of whom there will be none left in a generation. And I’m painting a picture of a city on the old fault-line of east and west. This is working against forgetting, and against time.”

– Anna Funder

Introduction

In October last year, 80-year-old Martin Manfred Naumann was sentenced to ten years in prison for a crime he committed while working under the East German Ministry for State Security, also known as the Stasi. Naumann, a former Stasi agent, was convicted of the 1974 murder of Czeslaw Kukuczka, a Polish father of three who had been trying to flee to West Berlin. Although increasingly few and far between, such cases expose how Germany is still grappling with the difficult legacy of its ‘second dictatorship.’ Nowhere is this better shown than in Anna Funder’s captivating work, Stasiland, which combines a detailed oral history of life behind the Berlin Wall with Funder’s own observations of post-reunification Germany.

Summary

Although first published in 2003, Stasiland begins a decade earlier in a newly reborn East Berlin: the street names have been changed, and the ballots are now free and fair. Yet, for many of the region’s inhabitants, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) is far from gone. Through her interviews with the people caught in this rift between past and present, Funder builds up a detailed oral history of life in East Germany. With first-person narration reminiscent of journalists such as Jon Ronson or Louis Theroux, we follow Funder on her seven-year-long journey of discovery, hearing from those who experienced the dictatorship first hand. Among her interviewees are former Stasi agents themselves, many of whom, although now stripped of their former powers, remain unpunished for their crimes. Funder also meets their victims: the ordinary citizens who had been on the receiving end of their tyranny. Examining how the Stasi’s destructive powers were able to infiltrate every aspect of their lives, she presents us with an unflinching view of the people still plagued by the lifelong consequences of Stasi oppression, even after the collapse of the so-called ‘Democratic’ Republic.

Throughout the course of the book, we see both Funder and her interviewees evolve, adapting to the changing Germany around them. On several occasions, our narrator actively mirrors her surroundings. She opens the book, for instance, hungover in a grey and crowded Alexanderplatz station: a metaphor for the hangover of the 40-year dictatorship. Funder’s decision to include unglamorous details such as this not only invites us into a vivid picture of the convalescing city, but instantly endears her to the audience, making the book immediately readable. Furthermore, very little, if any, prior knowledge is expected from the reader as Funder walks us through all of the necessary context, ultimately making Stasiland an ideal read for further exploration into this history.

border guards, 1989. Photo by Stephen Jaffe.

For me, Funder’s acute and witty observation stands out as one of the main strengths of this book. As critics Amy Mead and Amy Matthews note, she is an Australian living and working abroad, an outsider looking into a world that is not her own. Consequently, she is granted a unique perspective from which to notice even the smallest details, both in the oral histories recounted to her and in her unfamiliar surroundings. Whilst this outsider perspective alienates her somewhat from her interviewees, Funder puts this distance to good use. She quips about the absurdity of the world around her, bringing her Berlin surroundings to life with a cast of eccentric characters, many of whom she dubs with tongue-in-cheek nicknames. Furthermore, she does not shy away from the tragic irony of East German life. Whilst maintaining respect and professionalism for the victims, she exposes the almost darkly comic nature of the outdated system, pointing out the arbitrary nature of GDR laws, the over-the-top methods of the Stasi, and the organisation’s fundamental hypocrisy. For example, she shrewdly observes how one of her interviewees, a former Stasi agent and self-proclaimed SED-loyalist, now proudly drives an ostentatious BMW, clearly reaping the lavish benefits of life after the Wall.

Do not, however, be misled by Funder’s down-to-earth tone: her understated remarks tell us far more than may first meet the eye. In building up such a well-observed picture of the world around her, she clearly depicts both the new status quo and the complex history which informed it. Without a doubt, this is a serious work of journalism. At times, Funder even risks her own safety, repeatedly seeking out interviews with former Stasi agents and digging into their checkered pasts, despite warnings that “these men don’t want to be found.” As a result, Stasiland manages to expertly straddle the two genres: Funder simultaneously presents us with both a captivating oral history of the GDR and a closely observed piece of recent-affairs journalism, both of which offer important historical insight, as academic circles increasingly grow to appreciate the value of such oral sources.

Berlin fell into disuse. Photo by Jordis Antonia Schloesser.

Interviews

Through her interviews with those who are unable to leave the GDR behind, either out of trauma or loyalty, Funder weaves together a diverse set of perspectives about life in East Germany. Choosing to interview both victims and perpetrators, she does far more than simply offer a ‘balanced’ account of the past. Rather, she exposes how the lines between good and evil were blurred by this Orwellian state, as ‘ordinary’ citizens were pushed to inform on one another, and Stasi members were coerced by their own organisation.

At times, these discussions appear cathartic for her interviewees. Some even remember parts of their past which they had long repressed, and we are granted unique access to witness them ‘working through’ these painful memories in real time. Moreover, Funder appears acutely aware of her duty of care towards her interviewees. Where Stasiland could easily fall back on simplistic narratives of catharsis or justice, our author remains strikingly honest about the trials and tribulations of her research. At times, she even seems conflicted about the morality of her work and, to her credit, speaks openly about the emotional burden being placed on her interviewees.

“If I were Miriam and had to tell the most painful and formative parts of my life to someone, I’m not sure I’d want to see that person again either. Especially if my life had already been written down by other people, stolen and steered.”

One advantage of this format is that it leaves room for a great deal of nuance, something which is perhaps necessary given the sensitivity of this topic. Consequently, the GDR which Funder depicts is one of contradictions, acknowledging the diverse set of recollections all competing for a place within the history books. Several of her interviewees (even some who suffered at the hands of the Stasi) reflect positively on aspects of their former lives, praising the high rates of employment in the GDR. However, others feel differently. One interviewee, Julia, was denied work for years as a result of Stasi suspicion towards her and suggests that full employment was simply a propaganda myth. Throughout the course of the book, Funder beautifully captures several of these contradictions, showing how memories can vary, not only from the ‘official party line,’ but from person to person as well. Furthermore, she even shows how these contradictions can exist within a single person: her primary interviewee, Miriam, enjoys reminiscing about her life at sixteen, despite knowing that this marked the start of her lifelong entanglement with Stasi oppression.

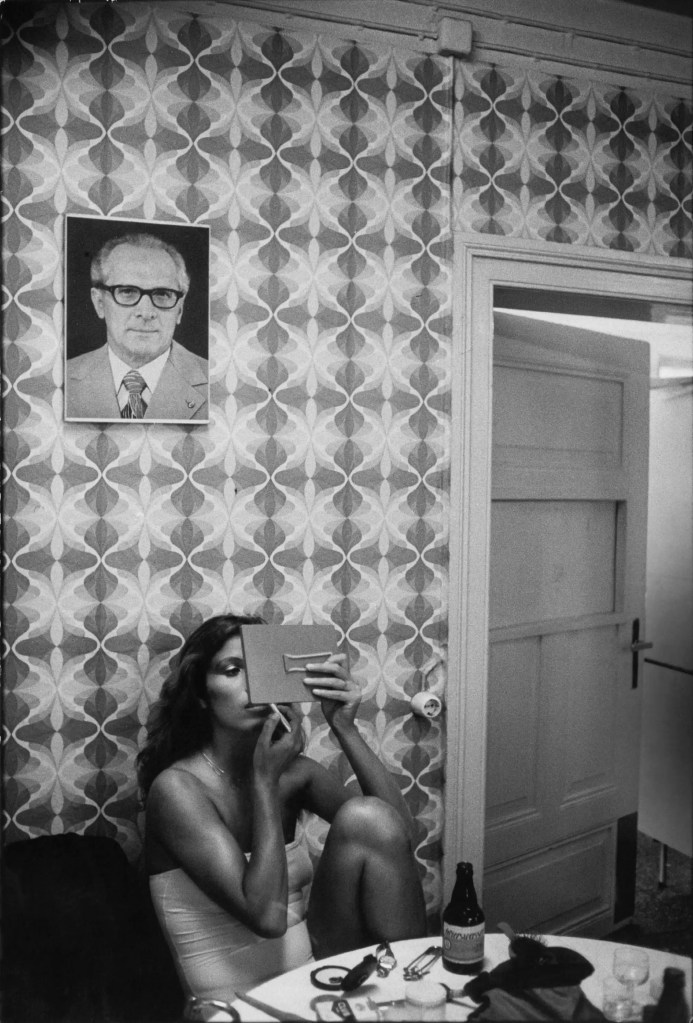

Here, I might suggest my only criticism of the book. To an extent, the title Stasiland may have the potential to subsume all other aspects of life in the GDR. Whilst undoubtedly memorable, it could imply that there was nothing outside of the Ministry for State Security: that East Germany and, more importantly, East Germans, did not exist without it. Of course, this has an element of truth. The mission of the Stasi was to infiltrate every corner of daily life and, naturally, no history of the GDR would be complete without it. Quite reasonably, this is the interpretation that Funder wishes to convey. However, one wonders whether some attention could also be paid to the private lives which GDR citizens fought to carve out for themselves, seeking out leisure and social lives beyond the prying eyes of the Stasi.

Remembering and Forgetting

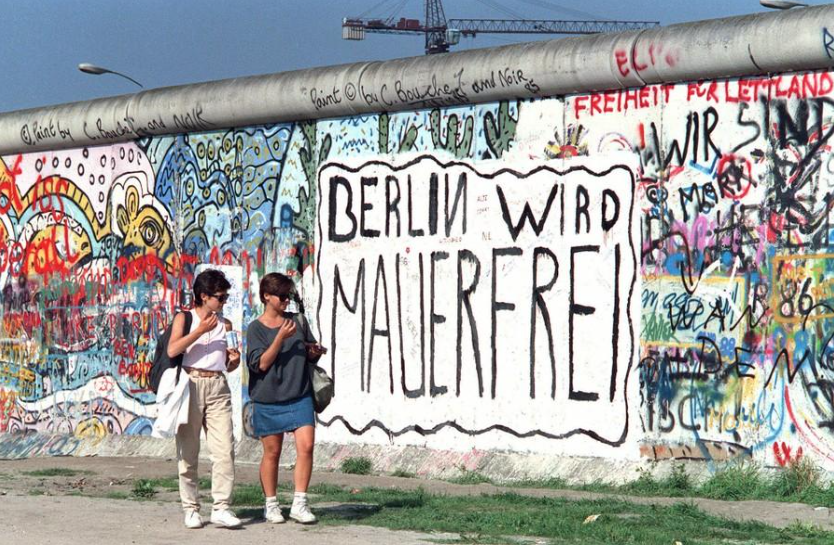

In my opinion, the crowning achievement of Stasiland is Funder’s depiction of the country around her and its struggle with forgetting. With the clarity afforded to her by her perspective as an outsider, she sketches a vibrant image of the new Germany, freshly patched up and convalescing from its forty year ordeal. Right from the start, it is clear that this Germany, although free of the tensions of the Cold War, is by no means free of its past. Indeed, as one of her interviewees reminds her, “everything that’s happened might [still] be reversed.”

Despite this uncertainty, Stasiland is optimistic. We see a country that is being carried by an undercurrent of hope, moving forward by deciding whether to remember or forget. One case in point are the so-called ‘puzzle women,’ who Funder visits as part of her research. Tasked with reconstructing an estimated 11,000 km of shredded Stasi files to return to the victims, their tireless work is just one example of the country’s commitment to confronting its history. In fact, there is a German word for this: ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung,’ meaning ‘coming to terms with the past.’ Throughout the book, Funder captures this process to a tee, offering interesting food for thought about the nature of memory and difficult pasts. How long after a traumatic event should it first be commemorated? How public should it be? Is there a ‘right’ way to do so?

Undeniably, memory of the GDR appears very much alive in the minds of Funder’s interviewees. By sharing their first-hand recollections, they offer a clear example of what memory scholars, Jan and Aleida Assmann, would call ‘communicative memory’: eyewitness recollections shared through everyday interactions. However, by the end of the book in 2000, a shift starts to appear. Whilst communicative memory of East Germany remains undeniably strong, Funder observes as the GDR first becomes installed in institutions such as the Leipzig Centre for Contemporary History and the Hohenschönhausen Memorial (a former Stasi Prison), watching as the official ‘history’ is written before her eyes. This marks the beginning of what the Assmanns would call ‘cultural memory’ (memories objectivised in the cultural sphere) and is, for me, precisely what makes Stasiland so special. By capturing a unique moment when cultural memory of the GDR first began to emerge, Funder shows us a country at a crossroads, stuck uncomfortably between remembering and forgetting. At one point, she sums this up well, asking:

“Isn’t a museum a place for things that are over?”

Conclusion

Thus, Stasiland brings us, in some ways, to where we are today. As the recent case of Martin Naumann demonstrates, the East German past is by no means over. For those who lived it, for both its victims and its perpetrators, it is far from gone. However, the fact remains that, day by day, the GDR is creeping ever further into cultural memory. As eyewitnesses inevitably start to decline over the coming decades, Funder’s work seems only set to grow in importance. By capturing Germany throughout the 90s and, more importantly, by preserving the testimonies of those who experienced the dictatorship first hand, she offers a direct line to the past. As the ‘official history’ of the GDR continues to be written, Stasiland is a powerful reminder that such stories are never black and white, and that, at their core, they are ultimately human.

By Lizzy Stott

Reference List

Assmann, Aleida. “Memory, Individual and the Collective.” In The Oxford Handbook of Contextual Political Analysis, edited by Robert E. Goodin and Charles Tilly, 210-24. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Assmann, Jan. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” Translated by John Czaplicka. New German Critique 65, 2 (1995): 125-33.

Funder, Anna. Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall. London: Granta, 2004.

Mead, Amy and Amy Matthews. “The Vessel and the Trace in Anna Funder’s Stasiland,” Antipodes 31, 1 (2017), 119-32.

Murray, Miranda. “Ex-Stasi officer sentenced to 10 years in jail over 1974 Berlin Wall killing.” Reuters. October 14, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ex-stasi-officer-sentenced-10-years-jail-over-1974-berlin-wall-killing-2024-10-14/.

Vock, Ido. “Ex-Stasi officer jailed for 1974 Berlin border killing.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c2kdyl90dewo#:~:text=The%20man%2C%20named%20as%20Martin,leave%20to%20democratic%20West%20Germany.

Image Credits

“4. September 1989: Ein Bild aus Leipzig geht um die Welt.” Photograph. Leipziger Volkszeitung, 2025.

Jaffe, Stephen. “West German school children pause to talk with two East German border guards beside an opening in the Berlin Wall during the collapse of communism in East Germany in November 1989.” Photograph. Stephen Jaffe Photography, 1989.

Mahler, Ute. “Consumer restaurant, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, 1984.” Photograph. The Guardian, 2021.

Schloesser, Jordis Antonia. “Occupied Kunsthaus Tacheles, Oranienburger Straße, Berlin-Mitte, 1997.” Photograph. OSTKREUZ/VG Bild-Kunst, 2024.

Schozlzel, Andreas. “Berlin wird mauerfrei.” Photograph. AP, 1988.

“Stasiland Front Cover.” London: Granta, 2004.