Echoes of Unrest: Unravelling the 1919 British Race Riots

Historical discussions surrounding racial tensions within twentieth century Britain have focused primarily on post Second World War events, placed in the context of decolonisation and mass immigration. The influx of non-white New Commonwealth immigrants following World War II, such as the landmark arrival of British Afro-Caribbeans on the HMS Windrush in 1948, as well as citizens from former British African and Asian colonies, transformed the nation’s diversity. Black and Asian British citizens have since faced considerable discord from portions of white Britons, evident through numerous events, including the 1958 Notting Hill riots, Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ anti-immigration speech in 1968, and the rise of the far-right National Front political party in the 1970s. The 1981 riots across various UK cities, the murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993, as well as the 2011 London riots are major examples of the tensions that have long stood between the black and Asian population and the police. That is why this article will investigate the foundations, proceedings and aftermath of racial violence that was experienced throughout Great Britain in 1919, particularly in the major port cities, such as Liverpool and Cardiff. In understanding the events that took place, one is able to view later violence that has demonstrated divisions of race in a broader perspective, rather than solely through a postcolonial lens.

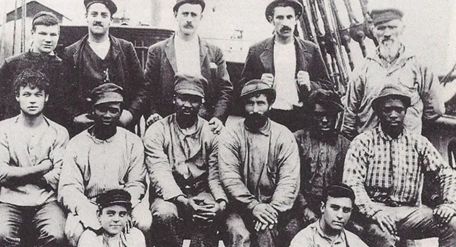

The end of World War I in November 1918 saw a surge of conscripted British men seeking a return to their previous employment. During the four-year period that these troops were fighting on the Western Front and beyond, the shortage of domestic workers meant Britain had to look further than their indigenous subjects. This was particularly the case in the employment of merchants and seamen on the docks. The use of colonial workers who had immigrated to Britain was not a brand-new operation. West African and Caribbean servants and slaves had been brought over during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as cheap labourers in the port of Liverpool, predominantly through the Elder Dempster Lines shipping company, with similar schemes used in the ports of Cardiff and London. As a result, by the turn of the twentieth century, small black populations had been established in major port cities.

However, the outbreak of the First World War provided colonial subjects with greater employment opportunities in Britain, where they ran the risk of greater social inequality in exchange for greater financial freedom. Workers from chiefly West Africa, the West Indies, the Middle East, China and Somalia arrived at the docks of Britain, and became employed in Britain’s shipping industry. The population of colonial workers grew steadily, with 5,000 black people (mostly men) residing within Liverpool by the end of 1918. Due to this influx of migrant workers, British soldiers returning from war found regaining employment more difficult than anticipated. Therefore, by the time that white Brits arrived back in their homeland, tensions between the employed colonial workers and white men seeking employment began to arise.

Frustrations from Glaswegian dock workers in January 1919 saw a series of protests against unemployment, as well as anti-immigration meetings. These events demonstrate how such workers associated unemployment with the colonial workers, who were believed to be taking the jobs from British men. As the months passed, rising contempt towards colonial seamen saw rapid growth nationally, exerting pressure on employers to dismiss the workers and replace them with white residents. Ethnic minority workers were more frequently sacked, such as in early June 1919, when 120 black Liverpudlian workers were laid off from a sugar refinery. This led to growing resentment within the colonial population, who asserted they had the right to equal treatment despite the lack of protection from the Home Office. Consequently, growing frustrations amongst both sides of the employment situation helped to stoke the fire.

Unlike the other port cities, such as Newport and Cardiff, where the authorities focused on the colonial workers as the escalators, the police in Liverpool surrendered the city to white aggressors. The 4th of June 1919 was the first major day of rioting in Liverpool, when black seaman Jim Johnson was seriously injured by two Scandinavian dock workers in a pub. Given that the perpetrators were white labourers from abroad, the incident illustrates the general mentality of white workers towards race, given that foreignness was only considered a threat to employment if their racial makeup was distinctly different.

Over the course of the next month, serious violence broke out. In Liverpool, black workers’ lodgings were destroyed by white perpetrators, who operated in mobs throughout the city and hunted for colonial workers to attack. Physical barricades were also built between the white workers and the colonial workers in other port cities, physically dividing people by race. These colonial workers were often arrested with greater promptness for retaliating or defending themselves, highlighting the difficulties that colonial residents faced. Not only were they placed in extreme danger by the white men attacking them, but the police failed in their diligence to ensure adequate safety could be offered. This shows that British policing failures in protecting non-white victims of violence was becoming normalised even before the mass immigration that followed World War II.

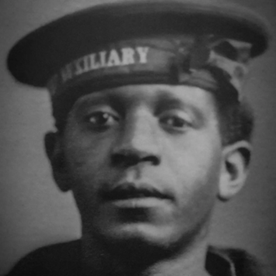

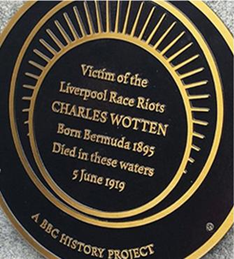

The tragic death of Bermudan fireman Charles Wotten in Liverpool on the 5th of June 1919 epitomised the grave consequences for non-white workers. After his house was stormed by police, Wotten managed to escape, rushing towards the docks, where he was pursued by the authorities and the white rioters. At the docks, he was either thrown in or jumped into the water, where he eventually drowned, while rioters and police looked on. The evidence is unclear regarding the specific circumstances of his death, but there is no question that Wotten’s death was provoked by the risks that the white inhabitants and police posed to him. Deaths, severe injuries, and the destruction of houses where non-white workers were living reiterates the idea that the authorities largely failed in defending subjects of the British Empire. The police’s actions which led to Wotten’s death exemplifies attitudes of the authorities towards black people seen in Britain since the Second World War.

The charges given to workers of colour arrested as a result of the riots were often significantly greater than that of the whites who were arrested. According to historian Jacqueline Jenkinson’s research into the 1919 riots, just over 53% of the arrested 161 black and Arab workers during the main phase of rioting in nine major port cities were found guilty, who were treated with little compassion compared to white defendants. The role of the police played an essential role in sentencing these workers, who nearly always accused non-white rioters of the aggravated use of weapons fuelling the violence, despite the majority of these rioters using said weapons as a form of self-defence. Judicial decisions in response to convicting rioters received much of its evidence from white witnesses and police reports, subsequently putting colonial defendants at a substantial disadvantage, and creating greater disparities between both sides of the rioting.

Press responses to the riots varied, although the theme of media outlets pushing concerns of miscegenation rather than unemployment as the principal cause of the violence was common. White men consistently took issue with miscegenation, or the interracial relationships most commonly between black men and white women. As a consequence, the concept of sexual immorality aggravated hostility, totalling to discontentment towards colonial workers. However, this was mainly absorbed as an issue by the middle-class rather than the more heavily involved working-class residents. For many newspapers, the perceived involvement of immigrant workers provided journalists with the ideal opportunity to enforce racist discourse into the mentality of its readers.

Amid the turbulence, the right-leaning, London-based newsprint The Morning Post published an article on June 13th, 1919, in which it claimed “a dominant white caste can govern a black race to the good of both. But it cannot be in terms of race equality.” White supremacist narratives such as this invigorated greater racial hate and helped spread the idea of superiority over the non-white population on domestic soil to regions of the country which had not actually experienced the riots firsthand. Impassioned by the racialised discourse gripping the nation and fears of miscegenation, the Home Office decided to act.

The government’s repatriation scheme was in whole quite an embarrassing failure. The Home Office’s offer of a meagre £7 to cover debts and resettle colonial workers back in their home country did not appear to be an attractive offer for black and Asian seamen. So much so, that between 1919 and 1921, only 3,000 of these colonial workers returned to their native countries (bearing in mind that the population of black people in Liverpool alone stood at around 5,000). It’s interesting to note that colonial workers romantically involved with white British women were exempt from the scheme, demonstrating the state’s paranoia surrounding racial mixing in its colonies. The scheme honed in the idea that non-white subjects were recognised as the root of the problem and thus needed to be removed, which helped to establish societal norms of what was expected of the behaviour of colonial workers immigrating to Britain.

For workers who evaded the scheme and continued to reside in Britain, matters were often made worse. The classification of the black, Arab and Asian population as ‘coloured aliens’ brought about by the 1920 and 1925 immigration laws only made it more difficult for colonial workers to keep their jobs, or if they had been dismissed, find new employment on the docks. Miscegenation between men of colour and white women continued to be abhorred by white men, although the government was unable to outlaw it explicitly. The idea of race in Britain as an identifying difference that characterised social status grew in prominence, encouraging discrimination and hatred towards non-white immigrants specifically. In recent years, the rioting of the port cities of Britain in the early twentieth century has enjoyed more research and commemoration. In Liverpool in 2023, a headstone for Charles Wotten was unveiled as a memorial of his tragic death. The statue acknowledges an important figure of Liverpool’s black history, as knowledge of the race riots grows through education provided by organisations and research project groups, such as the Liverpool Black History Research Group and the Liverpool Enslaved Memorial Project.

The 1919 race riots and the story behind them can be categorised by unemployment and miscegenation. Other factors, such as the perceived differences in civilisation, also had an influence. These elements are not just specific to the violence of 1919 – as can be seen in the 1958 Notting Hill riots and the 1981 riots – but do help to explain how these attitudes were conveyed in twentieth century Britain. As an overshadowed historical topic, the violence throughout 1919 demonstrates a tremendously crucial point in modern British race relations, contextualising authoritative responses to similar events during the twentieth century. The riots had a substantial impact on future police aggression towards non-white subjects and white attacks on black, Asian and ethnic minorities, establishing patterns of incidents that were not to be unexpected within British society. Furthermore, the racial violence of 1919 contributed to modern stereotypes about non-white populations in Britain. On this account, this has helped to shape the framework for future attitudes, behaviour and interactions between white and non-white Britons seen in the incidents of racial tensions after World War II.

Written by Jonah Ronder

Primary sources bibliography

British Newspaper Archive. “Stabbed to the Heart.” Illustrated Police News. June 19, 1919. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2022/10/26/the-1919-race-riots-in-britain/.

Historic England Blog. “Black seafarers of the First World War.” Photograph. Royal Museums Greenwich, c. 1914-1918. https://heritagecalling.com/2018/06/05/forgotten-seafarers-of-the-first-world-war/.

Mixed Museum. “Race Riots at Cardiff.” Western Mail. June 14, 1919. Accessed April 5, 2024. https://mixedmuseum.org.uk/amri-exhibition/the-1919-race-riots/.

National Archives. “Negro Riots. A Lesson for England.” Morning Post. June 13, 1919. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/1919-race-riots/.

Secondary source bibliography

BBC News. “Charles Wotten: Liverpool race riot victim to get headstone.” BBC News. June 6, 2023. Accessed April 3, 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-65813499.

Belchem, John. Before the Windrush: Race Relations in 20th-Century Liverpool. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014.

Bland, Lucy. “White Women and Men of Colour: Miscegenation Fears in Britain after the Great War.” Gender & History 17, no. 1 (2004-2005): 29-61.

Evans, Neil. “Across the Universe: Racial Violence and the Post-War Crisis in Imperial Britain, 1919-25.” In Ethnic Labour and British Imperial Trade, edited by Diane Frost, 59-88. London: Routledge, 1995.

Hunter, Virgillo. “Britain’s 1919 Race Riots.” BlackPast. November 28, 2018. Accessed March 30, 2024. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/events-global-african-history/britain-s-1919-race-riots/.

Jenkinson, Jaqueline. “Black, Arab and South Asian Colonial Britons in the Intersections Between War and Peace: The 1919 Seaport Riots in Perspective.” In Minorities and the First World War: From War to Peace, edited by Hannah Ewence and Tim Grady, 175-198. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017.

Jenkinson, Jaqueline. Black 1919: Riots, Racism and Resistance in Imperial Britain. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2009.

Rowe, Michael. “Sex, ‘race’ and riot in Liverpool, 1919.” Immigrants & Minorities 19, no. 2 (2000-2007): 53-70.

Wilson, Carlton. “Britain’s Red Summer: The 1919 Race Riots in Liverpool.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 15, no. 2 (1995-2001): 25-35.

This was all completely new information for me, very interesting indeed.

LikeLike