“I little thought I’d caught so tough a Tartar!” The Labour interest and late-Victorian Manchester

Introduction: Monolith

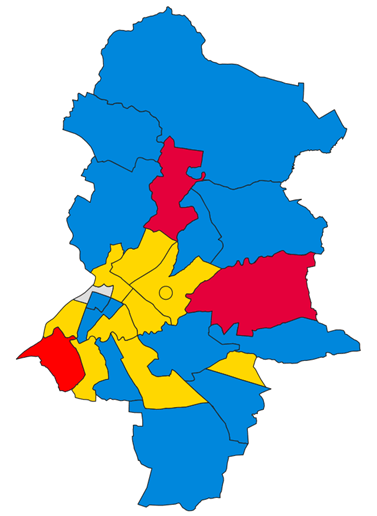

Manchester local politics is today synonymous with the Labour Party. Fifty-four years of majority control has turned the party’s dominance in the city council into a fact of life and allowed it to dictate the terms of engagement in almost all aspects of municipal politics. However, this privileged position was not a luxury afforded to those who first contested Manchester elections in the Labour interest. For those men, local politics meant navigating a patchwork of religious divisions, ethnic tensions, and fierce personal loyalties. The balance of power across the city was unfair and swathes of potential supporters were disenfranchised or disinterested. By the time Queen Victoria died in 1901, a small Labour bridgehead had been established, but in doing so, the independent Labour interest in Manchester, in the words of Martin Pugh, “did not transform working class political culture so much as adapt to it.” This article will look at late-Victorian Manchester where Labour emerged and how the nascent party conformed to its realities.

A short digression on sources

This article makes extensive use of the newspaper record. The competing papers of the city, notably the timidly liberal Manchester Guardian and the brazenly Conservative Manchester Courier, probably provide the best insight into late-Victorian Manchester’s political culture. Socialist papers such as Justice and Clarion provide a perspective from within the various strands that came to constitute the Labour Party.

The Bishop of Rome and the King of Ardwick: Manchester’s working-class political culture

Political culture in late-Victorian Manchester was deeply affected by the growing pains of Britain’s awkward transition to democracy. The requirement that local voters be ratepayers was a barrier to the local franchise for many in the working class. Those who could vote found their voices marginalised by the overrepresentation of the non-residential business vote in small city centre wards. Nevertheless, there were several parts of the city in which winning the vote of the working man became a prerequisite for victory. Another aspect of this transition was the role that parties played in local politics. Clubs and societies dedicated to the leading factions at Westminster predated the creation of the Manchester borough in 1838, and it was common for members of its council to belong to them. Despite this, party labels were generally not applied to local elections until after the Reform Act of 1867, which further extended the right to vote in the boroughs, and the development of better organised party campaign machines. These organisations mostly operated at the level of wards and parliamentary constituencies, party identities would not form an insurmountable division in the council chamber.The development of local party campaign machines engendered acrimonious contests in those wards where the vote of the working man mattered. Neither side was above employing underhand tactics to gain even the slightest advantage. One notable example from 1873 involved the Liberals of Ardwick and the Conservatives of St. Michael’s nominating several candidates in their respective wards bearing the names of opposition candidates in an attempt to confuse the electorate (this was before party labels were printed on the ballot). What this eventually led to was a bitter and sectarian political culture in Manchester’s working class wards whereby voters were not engaged by the parties on class lines but rather on grounds of religion and ethnicity.

As early as the 1870s, the Liberals in St. Michael’s, which contained the notorious Irish slum at Angel Meadow, printed the endorsements of the ward’s Catholic priests to mobilise the votes of its Irish residents. The Liberal appeal in the ward – and in neighbouring New Cross – continued to run along ethnic grounds and appeals for its Irishmen to “show their gratitude” for the party’s patronage would appear in green ink around the slums on the east side of Great Ancoats Street whenever election time rolled around. To the south of the city centre, Stephen Chesters Thompson, a brewing magnate who became the self-appointed “King of Ardwick”, conquered the Ardwick ward and the East Manchester constituency for the Conservatives with a populist appeal to the “loyalist” element. Through a mixture of anti-Irish rhetoric and generous patronage, Thompson constructed a loyal base of support in a thoroughly working class constituency for Arthur Balfour who was both an Old Etonian and the nephew of Lord Salisbury. One of the most notable beneficiaries of Thompson’s selective generosity, was Ardwick Football Club. Thompson funded a new stadium for the club and served as its President when it was elected to the Football League. Shortly thereafter, Thompson went bankrupt and his football club was rechristened as Manchester City.

The success of both the Liberal operation among the Irish of St. Michael’s and of Chesters Thompson in Ardwick suggests that working class voters in late-Victorian Manchester did not view themselves primarily in terms of class but along intersections of religion and ethnicity. It also demonstrates the extent to which party machines dedicated to winning the working class vote operated. These were two unavoidable realities with which the early Manchester Labour politicians had to contend.

Hurrah for Comrade Needham

The extent to which the Labour interest would contend with these realities, was answered in green ink on the bills of Richard Anderson, the Independent Labour Party’s (ILP) candidate, in an October 1894 by-election in St. George’s ward, Hulme. A sectarian appeal to the Irish, followed by the endorsement of the Hulme Liberal Association, demonstrates the extent to which the ILP understood the need to adapt to the attitudes and institutions which held sway over Mancunian politics if they wanted to win. A fact which undermined Anderson’s promise to usher in a “new epoch in local government”. Just two years after running their first candidates in the city, the ILP seemed to be entwined in the pre-existing Liberal Party infrastructure – so much so that when Anderson ran again without the endorsement of the Liberals, his unauthorised candidacy denounced by the Manchester & Salford ILP in Clarion and the St. George’s branch of the party was dissolved.

A porous relationship between the two parties is supported by Jesse Butler, one of the ILP’s first two councillors in Manchester, standing in a May 1898 by-election as a Liberal, just months after losing the same seat for Labour. In a broader context, this makes sense given that the Manchester & Salford Trades Council appeared to have been developing a relationship with the Liberal Party through the 1890s, with two of its leading figures, Matthew Arrandale and George Davy Kelley, being elected to the council under the Liberal banner even after the election of ILP members. It may have been assumed by the Manchester Liberals that the labour interest could fall naturally under its banner in the manner that the Irish vote had been. In retrospect, such an assumption seems premature but the ILP did undoubtedly benefit from utilising both local Liberal infrastructure and an element of sectarian politics in its first attempts at election. Electoral success finally came in 1894, with the elections of John Edward Sutton in Bradford and the aforementioned Jesse Butler in Openshaw, both in straight contests against the Conservatives. These victories were hailed in Clarion, Britain’s leading socialist journal, but failure to repeat this triumph in 1895 or 1896, left the ILP councillors at the mercy of the established Conservative and Liberal parties.

Opportunity knocked in 1896, with the controversy over Boggart Hole Clough in North Manchester, which was for many years, a space for open air meetings until the Parks Committee began to hand out fines to speakers. The issue became a cause célèbre in the labour and socialist movement, with Clarion carrying detailed reports of council proceedings on the matter and the speakers who refused to pay. George Needham, the Conservative chair of the Parks Committee, had a target placed on his head and was defeated in Harpurhey by Fred Brocklehurst, a journalist who had been sent to prison for refusing the fines. Clarion sarcastically thanked Needham and published a celebratory verse, mocking Needham for being a pork butcher.

“Hurrah for Comrade Neeham,

The friend of public freedom!

Long may his pork

And ham of York

The people fill and feed ‘em”

Brocklehurst’s 1897 victory allowed the ILP to return as many councillors as it had held before the election. Sutton won again in Bradford, but Jesse Butler, more focused on union organising than council work, was defeated. Ironically, Butler’s later run as a Liberal, split the anti-Conservative vote and allowed Comrade Needham to return to the council. The ILP might have stalled, but a breakthrough for the other party of the left allowed the socialist duo to become a gang of three. If Fred Brocklehurst’s victory represented the labour interest beginning to break away from established realities of Manchester politics, the Social Democratic Federation’s (SDF) victory at St. George’s, represented the party at its most adaptable.

Municipal Usefulism

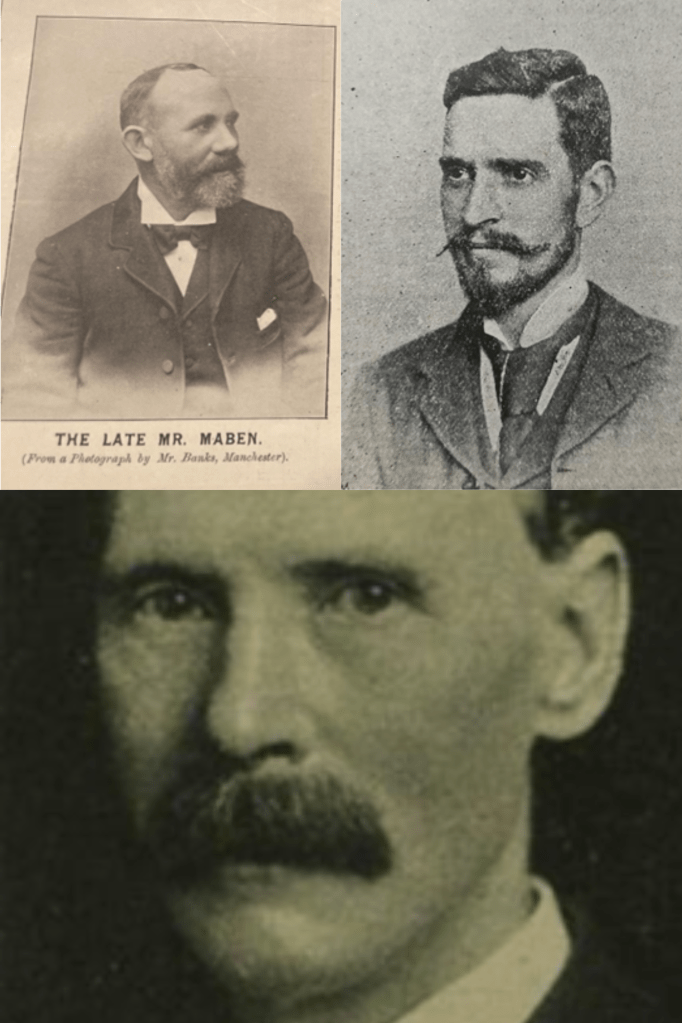

After the St. George’s branch of the ILP was dissolved, the SDF had taken its place in carrying the socialist banner in Hulme. An uninspiring result in 1895, led the SDF to ask William Maben to put his name on the ballot. Maben had already established himself in Manchester’s local affairs. Having moved to the city from Coatbridge as a young man, he was initially drawn to Liberal politics through the temperance movement. A rift with the Hulme Liberal Association in 1883 would not deter Maben. He became a lieutenant to Norbury Williams: the ratepayers’ crusader whose campaigns against municipal corruption and costly public works schemes had made him a celebrity. Being associated with Williams could only have been politically beneficial given the regard in which the man was held and the fact that he had received the most votes recorded for any candidate in an English election. Securing Maben’s candidacy was something of a coup for the Hulme SDF. After falling fewer than two hundred votes short in 1896, Maben pipped his Tory opponent to the post in 1897. He was undoubtedly elected due to his association with Williams.

Despite representing the SDF in the council, Maben rejected the socialist label and insisted that he was a “usefulist”, a vague term devoid of any real meaning. This rejection of ideology may be why he never corresponded with the SDF’s in-house paper, Justice, instead communicating through the Hulme SDF’s branch secretary. Maben was a pragmatist in his approach to municipal affairs. Most of his work in the council chamber was collaborative and focused on the issues of housing and pollution. He also influenced two of Norbury Williams’ campaigns that the Labour party adopted: s: one against an expensive culverting scheme and another over mismanagement inside the Cleansing Department. Supporting Williams and his eclectic Ratepayers’ Association, provides further evidence of the party conforming to existing political realities to establish itself, hoping to bask in Williams’ reflected glory.

Maben eventually split with the SDF over his refusal to support Fred Brocklehurst’s parliamentary campaign in South West Manchester. He quickly returned and was reelected unopposed in November 1900 but it was already too late. Terminally ill, and having failed to recuperate in the south of France, he returned to Manchester and died shortly thereafter. He was effusively eulogised in Manchester’s establishment press, albeit with his political leanings treated as an embarrassing afterthought, and given a civic funeral in Southern Cemetery. By the time of Maben’s death, the ILP and SDF had gained a small foothold on the council. In helping the party to conform to the realities of Manchester politics, Maben gave it the stability to eventually grow into the largest political group in English local government.

Conclusion

The emergence of the independent Labour interest in Manchester provides an insight both into late-Victorian political culture and development of the Labour Party more broadly. By attaching itself to established identities, causes, and institutions the nascent Manchester Labour interest would not redefine the terms in which working class voters saw themselves, instead conforming to the realities of the political culture of the city.

Written by Joe Kramer

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Clarion, 1893-1901

Justice, 1895-1901

Labour Leader, 1892-1900

Manchester City News, 1870-1901

Manchester Courier & Lancashire General Advertiser, 1870-1901

Manchester Guardian, 1870-1901

Manchester Lives 13, Manchester Central Library

Manchester Weekly News, 1885-1899

Secondary Sources:

Busteed, Mervyn. The Irish in Manchester C.1750–1921. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Hill, Jeffrey. “Manchester and Salford Politics and the Early Development of the Independent Labour Party.” International Review of Social History 26, no. 2 (1981): 171–201.

Kirby, Dean. Angel Meadow : Victorian Britain’s Most Savage Slum. Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2016.

McHugh, D. “A ‘Mass’ Party Frustrated? : The Development of the Labour Party in Manchester, 1918-31.” Salford: European Studies Research Institute, University of Salford, 2001.

McHugh, Declan. “Labour, the Liberals, and the Progressive Alliance in Manchester, 1900–1914.” Northern History 39, no. 1 ( 2002): 93–108.

Navickas, Katrina. Protest and the Politics of Space and Place, 1789–1848. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015.

Pugh, Martin. Speak for Britain! : A New History of the Labour Party. London: Vintage Books, 2011.

Vernon, James. Politics and the People : A Study in English Political Culture, C. 1815-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Wyke, Terry, Brian Robson, and Martin Dodge. Manchester : Mapping the City. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2018.