Disability on Stage: The Legacy of the Sideshow

Sideshows, dime museums, and freakshows. These exhibitions of bodily differences for profit are some of the most controversial aspects of entertainment history. A sideshow is an umbrella term for the smaller performance productions that focused on performers outside of the norm of traditional entertainment and would often accompany larger attractions such as circuses and fairs. Sideshows were staples in the dime museum tradition, which were inexpensive attractions that primarily showcased organic and artificial oddities and artefacts. The freakshow is a derogatory descriptor of the sideshow, as their performers were most often those with disabilities. While many will recognize the stage names of sideshow performers, their true names and stories are often forgotten, as is the disability performance of the 19th century. While the display of disabled bodies is present throughout time, the opening of P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in 1840, a dime museum, marks the beginning of the golden age of the sideshow. Throughout Europe and North America, sideshows became increasingly common in the entertainment industry, a staple of middle-class entertainment. In 1847, the British satirical magazine Punch would coin the growing popularity of these shows as “Deformito-mania.” These shows displayed performers with a range of physical and mental disabilities, with their physical appearance often accompanied by more traditional performance acts. Oftentimes, these shows were marketed as “educational,” appealing to public curiosity.

Freaks

The word freak has been used as a derogatory label to describe those with bodily differences, stigmatising disability and other characteristics deemed abnormal. The term was integral for the sideshow, creating a constructed persona for performers and categorising them into easily recognizable and marketable identities. Beyond physical appearance, show managers created the image that would sell best, often those that inspired the most mystique and curiosity. In the photographs or carte-de-visites often sold alongside show admittance, certain physical characteristics were emphasized alongside lavish costuming and sets in order to create a story that would appeal to mass audiences. In addition to biographies on the back of the carte-de-visites, there were signed testimonials from physicians, detailing the medical side of an individual’s disability to add a sense of authenticity to the acts. In the marketing of these sideshows, there was also an element of self-expression. Many performers appeared alongside their families and posed for photographers with great pride concerning their career and the abnormalities which made them famous. Nevertheless, performers and their images were heavily commodified, reduced to objects of entertainment for an audience’s enjoyment. Being a professional freak was an identity not associated with respectable employment or even being human, but rather being an extraordinary creature meant to mystify and amuse. These shows were often dubbed “pornography of disability.”

Individuals featured in these shows could reach unprecedented levels of fame. Under P.T. Barnum, Charles Sherwood Stratton, an individual with dwarfism who performed under the name “General Tom Thumb”, became an international celebrity adored by European critics for his ability as an entertainer. Stratton, born in Connecticut in 1838, noticeably ceased growing at a young age, leading Barnum to recruit him to join the American Museum at only four years old, where he was exhibited and subsequently trained in a variety of performing arts. His act included singing, dancing, and impersonations along with extravagant costumes and sets. He even performed for Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and an array of aristocrats in the picture gallery of Buckingham Palace in 1844. His marriage to fellow performer Lavinia Warren made headline news in the New York Times for multiple days during the American Civil War. It was Stratton’s performances that popularized the sideshow format across audiences in the Western world. Stratton amassed great wealth and fame, even becoming business partners with Barnum during his career.

Although the sideshow offered a unique opportunity for financial independence for many disabled individuals, most joined these shows and museums out of desperation. Employment opportunities were scarce for so many that the circus was the only option for somewhat stable employment. Other performers were sold into the circus either by their families or enslavers. There was an inherent power imbalance in the sideshow world; the degree of autonomy of the entertainers depended on their background and success in the sideshow business.

Colonialism and Science on the Sideshow Stage

The golden age of the sideshow and dime museum (i.e. the 19th century) coincides with a pop culture fascination with the “exotic.” Many show managers capitalized on what was considered to the Western eye as both physically and culturally strange, meaning sideshows frequently had a human zoo exhibition to accompany them. Disabled individuals from non-European backgrounds were not only presented as freaks but as savages, subject to both ableism and racism.

One of P.T. Barnum’s most famous performers was William Henry Johnson, believed to have microcephaly (a condition in which an infant’s head is smaller than expected, affecting brain development). He performed as a “pinhead” under the name “Zip the What Is It.” Although born in New Jersey to former enslaved individuals William and Mahalia Johnson, he was marketed as a survivor of an Amazonian tribe or as a creature who lived amongst the apes in Africa. For Barnum’s dime museum, he performed in the earlier years of his career in animal skins, acting erratically on stage. It is believed that the “What Is It” tagline associated with his advertisement, comes from a question asked to Barnum by Charles Dickens. The act overtime changed to reflect Johnson becoming more “civilized” including his costume changing to a tuxedo and the incorporation of musical instruments.

Johnson was later advertised as the “missing link” associated with Darwin’s theory of evolution, the connection between man and ape. He even testified in 1925 during the trial of John Scopes, the school teacher who then taught the theory of evolution, as this “missing link.” Johnson would be one of many sideshow entertainers used as evidence in the study of “racial science.” He gained a lot of notoriety throughout his long career for both his performances and his kind soul. Well into his 80s, Johnson was seen rescuing a little girl from drowning and became recognized as a good samaritan. Johnson, or the “Dean of the Freaks” as he was later known, lived a life of fame and success, found a community in the sideshow world, but this came at the price of constant dehumanization, as evident in his tagline.

The decline of the mainstream sideshow and dime museum corresponds with the rise of medical developments of the early 20th century. As eugenics and racial science became increasingly developed, sideshow performers became scientific commodities, and audiences gradually lost interest.. While often maintaining an air of amusement, the showcasing of disabled individuals became increasingly clinical as science gained value in popular culture. The continuous advancement of medicine and its place in culture coupled with a shift in mainstream sentiment towards disability directly led to the downfall of the sideshow as an acceptable form of entertainment, with many areas even making them illegal such as Michigan and Pennsylvania. Sideshow popularity diminished with many performers fading into myth or obscurity.

The Modern Sideshow

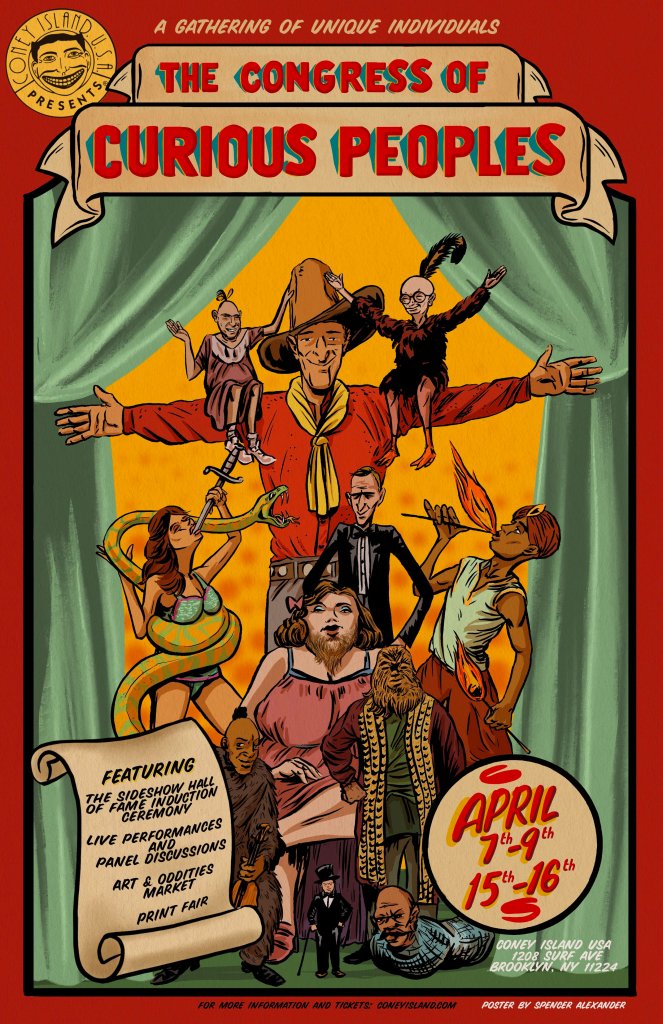

Although interest in sideshows declined, they existed well into the 20th century and even today. The Coney Island Circus Sideshow has continued to have annual performance seasons after its revival in 1980 with the creation of the Coney Island U.S.A. nonprofit that now oversees events and the Coney Island Museum. For many, it is a site of disability performance heritage inspiring careers in the arts for all body types. Mat Fraser, disability rights advocate with thalidomide-induced phocomelia (a malformation of the arms), credits Coney Island for his stable and prosperous show business career which includes stage and big screen performances. He’s known for his performances as an actor in American Horror Story, playing the drums during the opening ceremony for the 2012 Paralympics, and his performance in the “Cabinet of Curiosities: How disability was kept in a box” exhibition for the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester. Each year Coney Island U.S.A. holds their Congress of Curious Peoples. The event is a combination of lectures and performances meant to highlight multifaceted sideshow history at Coney Island and throughout the United States, bridging the gap between contemporary entertainers and disability and circus historians. Coney Island U.S.A. is one of the few lasting organisations facilitating the discussion of disability performance history and contributing to this unique form of entertainment today.

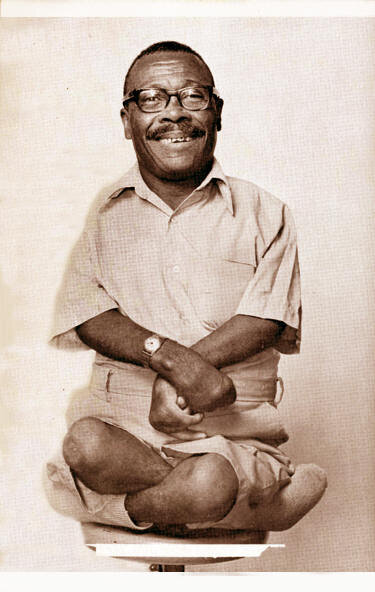

There are few contemporary sideshow performers which reach a status of notoriety. Otis Jordan, born in 1926, performed in sideshows and dime museums, primarily Coney Island, until the 1980s. Born with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita which causes permanent bentness of the joints, Jordan struggled with steady employment to aid his family. In 1963, Jordan met showman Dick Burnett and thus began his career in show business. His family-friendly acts were both educational regarding his condition and entertaining with one of his more famous acts showcasing his ability to roll cigarettes with his lips, leading to the stage name “Human Cigarette Factory.” A decade before the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 was passed, Jordan would fight in court for his right to perform after the Coney Island sideshow was sued due to its portrayal of disability that many deemed unfavorable. Otis Jordan’s story is one of empowerment in a landscape of exploitation. His story and those of other Black performers in the American circus can be found at the Uncle Junior Project, an online archive that preserves the legacy of these performers.

Conclusion

Although sideshows were born out of exploitation and dehumanization, today they are a celebration of diversity and are exemplary in how humanity can overcome prejudices. The history of these entertainers are close to being forgotten, just like many other uncomfortable aspects of the past. Sideshow performers are often an afterthought in disability history, reserved to a corner in an oddities museum out of shame and disinterest. Although a darker era of history, the sideshow remains an integral part of the legacy of disability in popular culture and their performers deserve to have their stories told.

Written by Kate Pointer

Bibliography

Backe, Emma Louise. “The Aesthetics of Deformity and the Construction of the ‘Freak.’” Student Anthropologist 3, no. 2 (2013): 27–42.

Davies, Helen. Neo-Victorian Freakery. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Durbach, Nadja. “‘Skinless Wonders’: ‘Body Worlds’ and the Victorian Freak Show.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 69, no. 1 (2014): 38–67.

Ferguson, Christine. “‘Gooble-Gabble, One of Us’: Grotesque Rhetoric and the Victorian Freak Show.” Victorian Review 23, no. 2 (1997): 244–50.

Kirkwood, Guy C. M. “Freak Show Portraiture and the Disenchantment of the Extraordinary Body.” Australasian Journal of American Studies 36, no. 1 (2017): 3–42.

National Disability Arts Collection and Archive. “Mat Fraser”. The NDACA. Accessed Feb 4, 2025. https://the-ndaca.org/the-people/mat-fraser/

Půtová, Barbora. “Freak Shows. Otherness of the Human Body as a Form of Public Presentation.” Anthropologie 56, no. 2 (2018): 91–102.

Stringer, Katie. “The Legacy of Dime Museums and the Freakshow: How the Past Impacts the Present.” History News 68, no. 4. (2013): 13-18.

Uncle Junior Project. “Otis Jordan. Uncle Junior Project. Accessed Dec 24, 2024. https://www.unclejrproject.com/otis-jordan.

List of image:

Alexander, Spencer. Congress of Curious Peoples Festival Pass. 2023. Coney Island USA, New York. https://www.coneyisland.com/event/congressofcuriouspeoplesfestivalpass

Cavalcade of Wonders. Freaks Past & Present. 1930s/1940s. Banner on painted canvas. Antiques and the arts weekly. https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/two-centuries-of-circus-memorabilia-cross-the-block/

“Human Cigarette Factory.” Carte de Visite. Coney Island, New York, 1987.

“The Fairy Wedding.” Souvenir Photograph. Library of Congress, New York, 1864.

“Zip Original What Is It.” Photograph. Ransom Center Magazine, Texas, 2013.