Should we retrospectively diagnose historical figures as autistic?

“Eccentric,” “aloof,” “obsessive,” “shy” – these are all labels used to describe numerous notable historical figures, both by their contemporaries and by modern historians. Before the growth of psychology in the late 19th and 20th centuries, these characteristics were regarded as simple facets of the people they were seen in- in no ways were they connected to contemporary understanding of mental conditions at the time. Yet, at the turn of the 21st century, a number of commentators proposed an explanation as to why a number of historical figures possessed these characteristics: these individuals were autistic. However, this perspective has been subjected to numerous criticisms from psychologists, historians and autistic people, with a host of arguments on both sides as to whether the practice should be accepted. This article will analyse a number of these arguments, taking into account historical, scientific and social perspectives to find an answer to this question.

First, it is worth providing a description of autism. Autism Spectrum Disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition affecting at least 1% of the global population, including the author of this article. Being a spectrum condition, its characteristics differ significantly from one autistic person to the next, with no two autistic people being alike. However, common characteristics include repetitive behaviours and thoughts (“stimming”), intense interests in specific areas, heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli, and differences in communication and social interaction. One commonly used term used parallel to autism is Asperger’s Syndrome, but this label is no longer used- anyone who has Asperger’s is by default autistic. Autism was first properly documented in the first half of the 20th century by a number of psychiatrists, with the diagnostic criteria having seen several notable expansions since then.

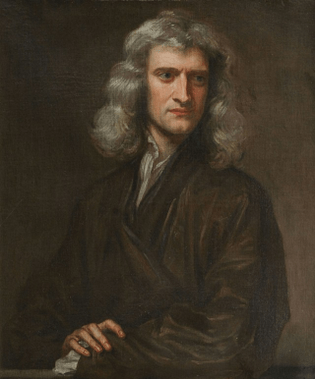

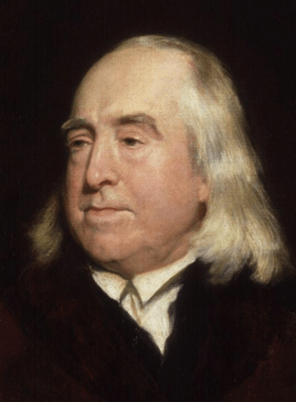

With that established, our attention can turn to the historical figures themselves. The list of names is long and varied, but notable names include scientists Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein and Henry Cavendish, US founding father Thomas Jefferson, philosophers Jeremy Bentham and Bertrand Russel, and artists Vincent van Gogh and Andy Warhol. All of these individuals have been considered autistic by a number of different commentators, with many of their notable behaviours being attributed to the traits listed above. Examples include Newton’s profound ability to concentrate on his work, Cavendish’s shyness and aversion to social interaction and Einstein’s desire for personal independence and autonomy. Observed and recorded by both contemporaries and biographers as mere eccentricities, these qualities would be later picked up on as evidence of autism. For instance, historian Ron Chernow described Thomas Jefferson as being “shy and aloof… seldom [making] eye contact,” as well as dressing in a “casual, almost sloppy” manner, accompanying his “slouching figure.” All of these could be recognised as traits of autism- a preference for being alone, lack of eye contact, sensory-friendly clothing and an unusual posture are all considered autistic characteristics by psychologists. Similarly, Jeremy Bentham was described by fellow philosopher, John Stuart Mill, as “knowing so little of human feelings,” yet also possessing an “indefatigable perseverance, [a] firm self-reliance,” without need of “other men’s opinion.” Some psychologists would attribute this description to a theory of mind deficit, a potential cognitive explanation for autism, whereby an individual is unable to form a conception of what others are thinking and feeling. With all this in mind, it is clear that there are a number of notable historical figures who exhibited traits that could be attributed to autism, something that has not gone unnoticed by observers in the present day.

Scientific and historical validity

The first- and arguably strongest- argument against the retrospective diagnosis of autism in historical figures is that, scientifically, it is impossible to do so. At a fundamental level, one cannot accurately diagnose somebody as autistic without having first met or observed them beforehand. This is something recognised by a number of autism experts- Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, head of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge, has previously asserted that a “definite diagnosis” of autism in a deceased person is not possible, and Doctor Oliver Sacks, a neurologist and historian of science, has claimed that the evidence used for many retrospective diagnoses is “thin at best.” Thus, what is left is mere speculation. It is certainly feasible that many of these figures were autistic, but a diagnosis has to be founded on more than simple theorising developed from historical records and biographies.

Some psychologists have gone as far as to describe retrospective diagnosis as a “cottage industry,” portraying it as a practice of popular science or even pseudoscience, not to be undertaken by serious psychologists. What undercuts this perspective, however, is that some of the most high-profile retrospective diagnoses have been made by well-regarded autism or psychology experts, including those mentioned above. For example, Baron-Cohen’s recognition of the impossibility of “definite diagnosis” has not stopped him from suggesting that both Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein were both autistic, and Sacks had no qualms over his diagnosis of autism in Henry Cavendish. The fact that retrospective diagnosis has been practised by such esteemed figures in their field gives it a sense of legitimacy, recognising that despite its speculative nature, it is not a wholly worthless exercise.

The question of possibility, however, is not just a scientific one, but a historical one as well. In response to claims that Thomas Jefferson may have been autistic, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation emphasised that such diagnoses often rely heavily on secondary sources, such as biographies, over primary sources that may reveal more accurate information. One thing often highlighted within these criticisms is that access to information about historical figures’ childhoods is often limited, with key details frequently incomplete or absent. Since childhood behaviour and experiences are important elements of any autism diagnosis, the lack of this information presents a further problem retrospective diagnosis. The Foundation attributed this set of issues to the fact that diagnoses are often made by “autism experts about historical figures,” not “historians about autism,” highlighting the need for more rigorous historical methodology.

Autism’s place in history

One positive consequence of retrospective diagnosis is that it helps to establish that autism, and autistic people, have been around for hundreds of years. This may seem obvious to some, but conspiracy theories such as the fraudulent notion that vaccines cause autism have contributed to many believing that autism is a new condition, only emerging in recent decades. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Autism as a neurotype has been present for much of human history, something recognised as early as the 1940s by Leo Kanner, one of the first psychiatrists to distinguish autism as a distinct condition from disorders such as schizophrenia.

Kanner recognised that many of those previously thought of as “lunatics” or “imbeciles” were likely autistic, which provided a historical background to his research and legitimised his discoveries. Similarly, retrospective diagnosis can help to strengthen awareness of autism amongst the general public by associating it with well-known historical figures, demonstrating its longstanding presence in human society. By making it clear that autistic people have always been here, work such as this provides a historical context that helps to raise awareness about the problems autistics face within society. On the other hand, retrospective diagnosis of autism can be used to perpetuate harmful stereotypes of autistic people. For example, the historical figures named here – Einstein, Newton, Cavendish, Jefferson, Bentham- share many similarities.

Many of them are scientists or philosophers, in particular physicists, and almost all were male and white. This is unsurprising- for decades, autism was (and in many ways, still is) seen as a condition that affects males more than females, and is predominantly diagnosed among white, middle class children. It therefore stands to reason that historical figures thought to be autistic come from this demographic. Furthermore, popular stereotypes of autism, especially Asperger’s Syndrome, assume that autistic people are hyper-intelligent, possessing an affinity for mathematics and science that compensate for our supposed lack of sociability and humour. This perception of autistic people is widely at odds with reality, yet it remains fresh in the minds of many neurotypicals’ understanding of autism, partially due to noteworthy historical figures who are supposedly autistic fitting this description. This reinforcement of the idea that all autistic people are white men or boys engaged predominantly in the sciences is profoundly damaging, as it makes it harder for people outside this demographic- women, ethnic minorities, or individuals whose autistic traits simply present differently- to access the diagnosis and often vital services they need.

Who to focus on?

Returning to a historical perspective, there is another criticism that can be made. Retrospective diagnosis’ focus on “big names” obscures the stories of everyday autistic people throughout history. Almost all of the individuals mentioned in this article were successful in life, being recognised in their time as pioneers in their fields, and hailed to go down in history amongst the other greats. But where does that leave everyone else? When conducting his research in the 1940s, it was not the “great men” of history that Kanner recognised as past examples of autism, but ordinary people, many of whom had been severely mistreated as the result of their different characteristics. Who is there to tell their stories? Rather than focusing on figures who fit prevailing stereotypes of autism, historical and scientific research should seek to explore how ordinary autistic people lived their day-to-day lives in a time before their characteristics and struggles were recognised or understood. The possibilities are vast- how did autistic people live in the Mediaeval era? Were they artisans who turned their special interests into trades, or monks and nuns who welcomed a quiet life of solitude? What about the Victorians- how did autistic people manage to conform to the strict standards of respectability? Did they appreciate the clear set of social guidelines to follow, or were they baffled by the arbitrary nature of social classes? Questions of this kind would unveil a rich tapestry of lives and stories across the years, grounding autism within wider social history. Furthermore, whilst retrospective diagnosis may help to de-stigmatise autism for the general public, looking at autistic history through this lens would undoubtedly be more inspiring and helpful to autistic people today. Instead of being compared to the greats of history- often in a negative fashion- we would at last be able to understand how our forebears managed to survive and even thrive in eras gone by, and to apply that history to our own continuous struggle to live in this world that was not made for us.

To conclude, the question of whether retrospectively diagnosing historical figures as autistic is right or wrong is a difficult one, but that does not mean the answer has to be unclear. First, it must be acknowledged that it is impossible to say for certain whether any historical figure was autistic or not: proper diagnosis cannot be issued to deceased individuals. Yet, it can also be recognised that the practice is not without legitimacy, and that if it finds a way to overcome its current issues with source evidence, it may gain a position as a respectable exercise of speculation. However, whilst this can be useful in de-stigmatising autism and grounding its position in history, it frequently risks falling into harmful and damaging stereotypes that counteract any potential benefits. Ultimately, though, the shift towards exploring the lives of ordinary autistic people informs this article’s answer. Retrospective diagnosis should not necessarily be stopped- if enough caution is exercised, there is nothing wrong with a suggestion that a certain historical figure may have been autistic. But the full efforts of autistic history should be redirected towards looking at the lives of ordinary autistic people both before and after the condition was identified in the 20th century, telling the stories of their experiences, struggles and successes, fully grounding autism in the history of human society and making it clear that autistic people, no matter our characteristics, have always been here, and always will be.

Written by Oscar Hilder

Bibliography:

Berkes, Anna. “Diagnosing TJ”. Monticello. February 19th, 2009. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://www.monticello.org/exhibits-events/blog/diagnosing-tj/

Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. London : Head of Zeus, 2016.

Falck-Ytter, Terje and Loden, Sofia. “The perils of suggesting famous historical figures had autism”. The Transmitter, September 22nd, 2020. Accessed November 24th, 2024.

Goode, Erica. “CASES; A Disorder Far Beyond Eccentricity”. The New York Times. October 9, 2001. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=news&id=urn:contentItem:445G-5VT0-0109-T0S9-00000-00&context=1519360

Hayton, Darin. “Isaac Newton was Autistic, or Not”. Darin Hayton- Historian of Science (blog), December 31st, 2015. Accessed November 24th, 2024.

James, Ioan. Asperger’s Syndrome and High Achievement : Some Very Remarkable People. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2005. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/york-ebooks/reader.action?docID=290867

James, Ioan. “Singular scientists.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (2003) vol. 96,1 : 36-9. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC539373/

Kneller, Godfrey. Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton. 1689. Oil on canvas, dimensions unknown. Isaac Newton Institute, Cambridge. https://exhibitions.lib.cam.ac.uk/linesofthought/artifacts/newton-by-kneller

Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Sir_Isaac_Newton,_1689.jpg

Ledgin, Norm. Diagnosing Jefferson. Arlington: Future Horizons, 2000. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://archive.org/details/diagnosingjeffer00ledg/mode/2up

Lucas, P & Sheeran, A. “Asperger’s Syndrome and the Eccentricity and Genius of Jeremy Bentham”. Journal of Bentham Studies (2006) 8(1).Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://journals.uclpress.co.uk/jbs/article/id/1163/

Mill, John Stuart, Bentham, Jeremy, Ryan, Alan, Bentam, Ieremi︠a︡, Bentam, Dz︠h︡eremi, Bentham, Jeremías, Bentham, Jérémie, 邊沁, and Beauchamp, Philip. Utilitarianism and Other Essays / J. S. Mill and Jeremy Bentham ; Edited by Alan Ryan. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1987.

Muir, Hazel. “Did Einstein and Newton have autism?” May 3rd, 2003. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://institutions.newscientist.com/article/mg17823931-000-did-einstein-and-newton-have-autism/

Muir, Hazel. “Einstein and Newton showed signs of autism”. New Scientist. April 30th, 2003. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://institutions.newscientist.com/article/dn3676-einstein-and-newton-showed-signs-of-autism/

Silberman, Steve. Neurotribes : The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter about People Who Think Differently. London : Allen & Unwin, 2015.

Smith, J. David. “Diagnosing Mr. Jefferson: Retrospectives on Developmental Disabilities at Monticello”. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (2007) 45 (6): 405–407. Accessed November 24th, 2024. https://meridian.allenpress.com/idd/article-abstract/45/6/405/1309/Diagnosing-Mr-Jefferson-Retrospectives-on?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Images:

Peale, Rembrandt. Thomas Jefferson. 1805. Oil on canvas, 71.1 x 59.7 cm. The New York Historical, New York City. https://emuseum.nyhistory.org/objects/41588/thomas-jefferson-17431826

Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeremy_Bentham_by_Henry_William_Pickersgill_detail.jpg

Pickersgill, Henry William. Jeremy Bentham. 1829. Oil on canvas, 204.4 x 138.4 cm. National Portrait Gallery, London. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw00519.

Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeremy_Bentham_by_Henry_William_Pickersgill_detail.jpg

Photographer Unknown. “Oliver Sacks”. Photograph. Accessed from Wikimedia Commons, 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oliversacks.jpg

Turner, Orren Jack. “Albert Einstein”. Photograph. Library of Congress, Washington, 1947.

Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Einstein_Head.jpg

Walsingham, Thomas. History of the abbots of St Albans. 1394. Miniature, dimensions unknown. British Library Archive, London. https://imagesonline.bl.uk/asset/1009

Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Richard_of_Wallingford.jpg

Wilson, George. Frontispiece of The Life of the Hon. Henry Cavendish. 1851. Drawing, dimensions unknown. Accessed from Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cavendish_Henry_signature.jpg