Human Stories at Goathland Station

Introduction

On the 12th of February 1864, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph made something of an appeal. They called for ‘the abolition of what is known as the Goathland incline’¹ – certainly a rather extraordinary demand to make against an inanimate gradient of dirt and rails! However it was not completely unwarranted. These earthworks had recently cost two people their lives², and this was not the first time a serious accident had happened in this location. The inline in question was a key part of the original formation of the railway line between Whitby and Pickering which had opened in 1836, a line built as a horse-drawn tramway and with relatively lightly engineered track and earthworks as a result. By the 1860s, this steep gradient, with its outdated, gravity-based method of operation, had clearly become a thorn in the side of the North Eastern Railway (NER) that had taken over the line in 1854³, not least due to the unfortunate tendency some trains had to become runaways down the gradient, with sometimes fatal results, as mentioned above.

Eventually, the NER began work on deviating the line around the side of the valley near Beck Hole, to ease the gradient enough to allow steam locomotives to haul trains throughout without having to hand over to the gravity-worked incline. This deviation opened in 1865, and along with it, a new station to serve Goathland⁴.

This new station (figure 1) formed the focus of the author’s master’s dissertation⁵, which looked to prove the efficacy of applying the methods of buildings archaeology to station buildings, no understanding of the usefulness of this combination having existed previously.

However, a dissertation focused on such a strict academic goal necessarily leaves out a wealth of information that is nonetheless interesting and historically illuminating to explore. In terms of Goathland, these were the human stories. Slices of life tales unearthed or recontextualised during the research deserve to be told. This is what this article looks to do, hopefully demonstrating along the way the usefulness of the archaeological approach taken in creating a fully rounded picture of life in times gone by.

‘We the undersigned…’

A fascinating insight into life at Goathland station and on the North York Moors more generally in the Victorian period, can be gleaned from the resident’s 1871 plea for more undercover waiting space at the station. This came in the form of a petition that they submitted to the NER⁶.

The wording of this petition reveals a number of intricate details about how the people of Goathland viewed and interacted with the station. In it, they ‘beg respectfully’ to raise the issue of ‘the urgent want of a waiting room at the station’ – emotive stuff, and clearly designed to grab the attention of board members or regional managers in amongst what must have been mountains of paperwork.

The petitioners clearly held themselves and their village in high esteem, too:

“As the stormy season is now approaching, we trust that you will promptly afford us that

comfort which is not denied to less important stations”.

Very interesting, and suggestive of a notion that having a well equipped and maintained station in their town, now formed a part of the pride of the area in the eyes of the inhabitants. This makes sense, it being the gateway that welcomes the increased number of travellers the railway can bring with it, and first impressions, as ever, being everything! Indeed this increase in tourism is mentioned in the petition as being another reason for needing the additional waiting space, saying that ‘they also suffer great inconvenience and discomfort from the absence of shelter’ – a clever tactic indeed, tourism traffic being an important source of revenue for railways⁷.

It is hard not to note how the positive, even emotional, attitude to the station presented in the petition, stands in stark contrast to the widespread feelings of distaste that ruled public opinion about the railways just a few decades earlier⁸. This speaks much to the earlier days of the romanticisation of the steam railway that we are now familiar with through TV and film. A very illuminating study might be done on the wording of similar petitions to railway management, if any exist. Certainly, this small example begins to shed light on aspects of railway and social history that are eternally hard to pin down: the way people felt and how these feelings were manifested in these buildings.

For these feelings did manifest something – the village folk got their wish, and a new waiting shelter on the opposite platform to the main station building was constructed for them. You can still see it today (figure 2). A small monument to the power of persuasion!

Living room or waiting room?

Goathland station has undergone numerous phases of alteration since its construction, and it was important to chart this complexity to understand the significance of these changes. The station building has always been a combination of a public waiting room and ticket office space, and the private domestic space dedicated to the station master and his family. The charting of the changing floor plan therefore allows a picture to be painted of the interaction of these different lives, crammed into one building. In turn we might better understand the interactions of the people involved.

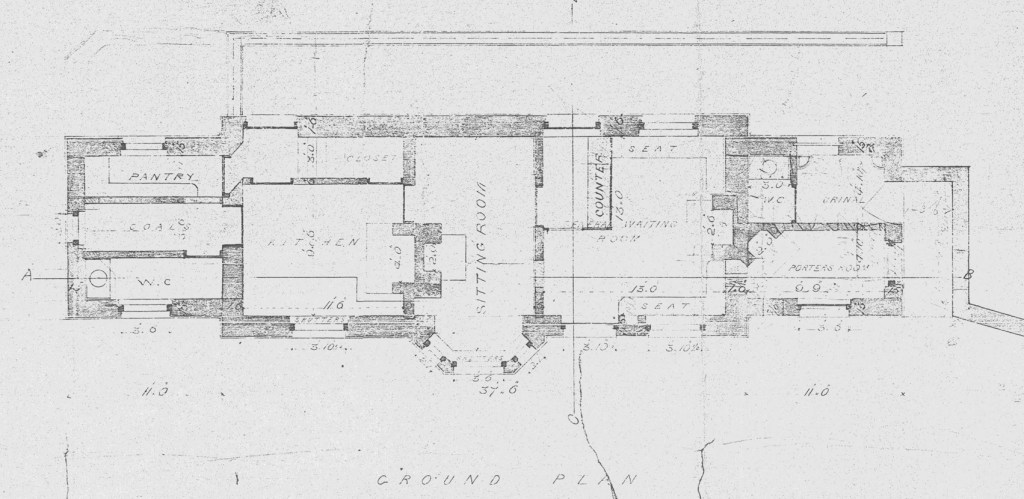

Originally there was a surprising degree of openness between the public and private areas of the station. The ticket office seen today did not then exist, tickets instead being purchased from a counter in the waiting room. The counter was accessible via a single door straight from the kitchen of the station house, which would also have effectively been used as the family’s living space, this version of the plan lacking a living room entirely (figure 3).

Station masters of the time would have been busy men, so the implication here is that members of his family, rather than otherwise employed members of the railway staff, would have been expected to sell tickets.

One can imagine the station master’s wife leaving what she was doing in the kitchen, to sell a ticket, or to deal with an inquiry. Indeed, if it was not expected that the family would assist in running the station, why should this door exist, and why should the counter be placed where it was, directly in front of where the family would enter the public part of the building? Later rebuilds of the station removed this feature entirely, showing that clearly this was no mere convenience for the station master to access his workplace.

It is interesting to consider the implications of this door and counter, insignificant as they may initially seem. They speak to a way of living and working that challenges the traditional ideas of the separation of public (masculine) and private (feminine) spheres in Victorian England. This suggests the station master’s family were involved on some level with the day to day running of the station, which as the next section will discuss, was a key centre for the community that used it.

It is tempting to consider the small moments that may have played out within the odd concoction of public and private space. Curious children (or perhaps even adults!) peeking round the door to see how their station master lived. The farmer’s wives chatting to the station master’s over the counter on their way into Whitby for the market. All theoretical scenarios of course, but it is hard not to imagine how this odd way of living might have played out.

Vignettes of station life

This final section will examine a few smaller slice-of-life type stories from later in the station’s life. During the author’s master’s research, a transcript was rediscovered from a conversation with Oswald Gillery, son of Fred Gillery who had been station master at Goathland between 1926 and 1933⁹.

This document gives an intriguing insight into the daily life of the station, how railway operations there were conducted, the role of the station master, and so much more that helped to inform the understanding that the dissertation sought. These tales range from the fascinating to the humorous!

More can be gleaned about the pride that was attached to these country stations by Fred Gillery’s approach to maintaining his.

“No, he was a very proud man was my father, he was very proud to be at Goathland; he liked to keep the station in very good order… they used to spend hours and hours (the porters) raising these seeds and pricking them out and putting them into the garden which went almost all the length of the platform” ⁹.

Clearly then the station and its gardens were key to the pride of those that worked there, not just to the station master but the porters who worked under him. It is difficult to imagine such attention to detail on the railways of today. This pride remained strong well after Gillery left the station, numerous ‘best kept station’ awards from the station’s time under the nationalised British Railway in the 1950s and 60s still hanging in the office.

Another story revolves around Gillery’s quest to receive running water at the station. Despite the arrival of the railway almost 100 years previously when Gillery was at Goathland, the Moors were still a lonely environment with few modern comforts. It would not be until 1930 that a single cold tap would be installed in the station. Even then, not without a battle – “No, I’m not paying that! I’d expect a pipe from a brewery for that”, is how Gillery’s son recalls the conversation going⁹.

Humour and pride were clearly a part of life at the station but so, it seems, was camaraderie. Typical of safety regulations of the time, Oswald recalls that trains in the sidings at Goathland were sometimes shunted using gravity, rather than a locomotive. The brakes would be let off, and the train would roll downhill along the yard to where it was needed.

Once however, the train clearly didn’t pick up as much speed as usual and ground to a halt across the lines used to exit the yard, and trapping a locomotive in the sidings! Gillery could perhaps feel the district inspector already breathing down his neck at such an incident, and soon set to. Recalls Oswald: “My father, he got a… large pole, and he got ever so many men to hold this pole on the buffer beam of the engine and the other end was on the buffer beam of the coaches and then the engine just pushed these coaches clear.”⁹. Not a move that would please modern health and safety regulators, but it demonstrates the attitude of railway work of the time well.

Conclusion

Hopefully these stories have given you an insight not only into the human stories that can be found in a country station, but also provided an idea of how these stories have been illuminated and recontextualised by the archaeological approach taken to the material. It has allowed the interplay between the counter and the living spaces to be explored; the petition and its results to be understood. The story about Gillery’s minor battle to get running water installed may not have made sense had the phasing of the building and the fitting of its taps not been investigated.

Railway stations are the source of endless stories like these. If we are willing to look for these stories, and to be creative and methodical in how we do so, they can also provide us with a deepened understanding of the societies that built them in ways no other structure can. The interplays between industry and society, public and private space, different classes and genders, are unlike those found anywhere else.

Next time you’re in a station, big or small, I encourage you to look around at the snippets of life taking place there. Soon all those people will move on, and in their place only the station will remain. How many others have stood on that platform before them? How might we tell their stories? Or how might you want yours to be told in the future?

Written by William Plant

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

¹ Sheffield Daily Telegraph:

12/2/1864 Page 3 Frightful Accident on the North-Eastern Railway.

² Sussex Advertiser:

26/12/1836 Page 4 Miscellaneous.

⁹ North Yorkshire Moors Railway Archive:

Transcript Transcript of a conversation with Mr Oswald Gillery.

Recorded by Margaret Smith with Mark Sissons on 1st June 2011.

Secondary Sources:

⁸ Brandon, D. Brooke, A. (2019). The railway haters: opposition to the railways, from the 19th to 21st centuries. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Transport.

⁷ Major, S. (2017). New crowds in new spaces: railway excursions for the working classes in

north west England in the mid-nineteenth Century. Transactions of the Historic Society of

Lancashire and Cheshire. Vol. 166, pp.93-115.

⁵ Plant, W. (2023). A parish church of steam: the history and recording of Goathland station. Unpublished master’s dissertation, University of York.

⁴ Suggitt, G. (2005). Lost railways of North and East Yorkshire. Newbury: Countryside Books.

⁶ Thompson, K. (2020). Goathland in folk lore: fact and fiction. Edinburgh: Inkjet.

³ Tomlinson, WW. (1915). The North Eastern Railway: its rise and development. Newcastle: A.

Reid & Company.