A Comparison of the ‘An Allegory of the Tudor Succession’ Paintings

Introduction

Monarchical portraiture has existed for millenia across many cultures. Depicting a powerful ruler through paintings, writing, music and statues has its roots in propaganda and shows a desire to be remembered once deceased. Those who could afford it worked hard to ensure their image outlived them, and it mattered so much so that other rulers would work just as hard to remove their predecessors from the historical record. In particular, the Egyptian pharaohs post-Amarna period practised damnatio memoriae, the act of erasing the names and destroying depictions of predecessors to remove them from history. In England’s Early Modern period, the regent’s drive to depict oneself persisted, creating some of the most iconic examples of royal portraiture in English history, such as Hans Holbein’s Portrait of Henry VIII (Fig 1) and Sir Anthony Van Dyck’s Triple Portrait of Charles I (Fig 2).

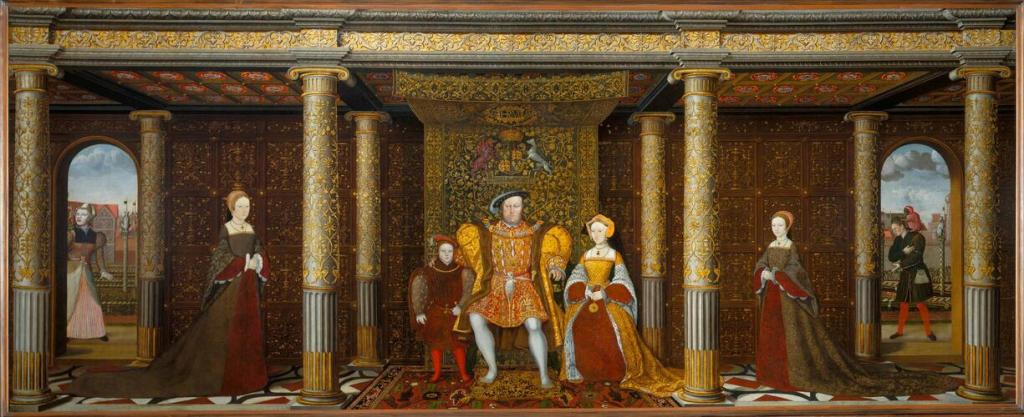

In this article, I investigate royal portraiture of the Tudor period, specifically through two almost identical paintings depicting Henry VIII and his children, all of which ruled England. The first is named The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession by Lucas de Heere from 1572 (Fig 3) and the second is An Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII by an unknown artist from 1590 (thumbnail figure). While the concept of copying a painting almost exactly may seem odd and plagiaristic to the modern artist, copying paintings was a respected art form that assisted the distribution of images around the world for propaganda purposes (a painter who copied others’ work even had their own name – a ‘copyist’). However, what is interesting about comparing these two paintings is what the later artist chose to recreate, what they chose to change and what this tells us about the image that Elizabeth wanted to communicate in her early and late reign.

Analysing the Similarities

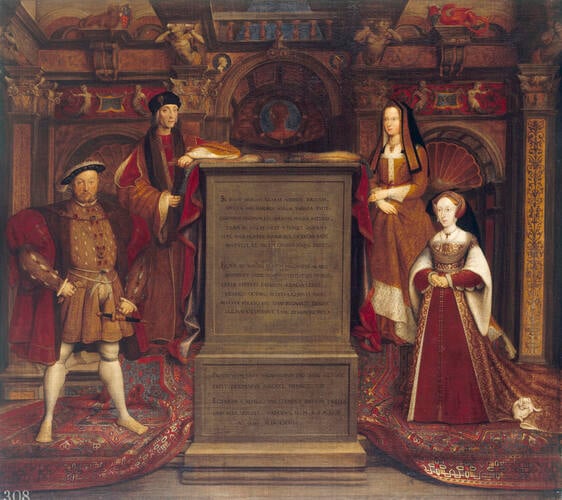

The first painting (Fig 3) is attributed to Lucas de Heere, a Flemish Protestant who was fleeing persecution in Belgium. It was commissioned by the fellow Protestant Elizabeth I and completed in 1572, when Elizabeth was fourteen years into her reign. It was intended as a gift to Sir Francis Walsingham, the then English Ambassador to France and another devout Protestant, after enabling the Treaty of Blois in 1572, creating an alliance between France and England against Catholic Spain.

The paintings take the form of an allegory, a form of art that makes heavy use of metaphors, classical personifications and gods. Allegorical paintings were also a popular form to depict real life people and were an in-demand style with European royal families. They were frequently used to depict the Tudor family, such as Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Whitehall Mural (Fig 5) and an unknown artist’s The Family of Henry VIII (Fig 6). These paintings act at first glance as a family portrait, frequently depicting both living and dead relatives at the peak of their reigns and allowing them to appear ‘together’ in a sense.

Other allegorical paintings depicted monarchs directly interacting with gods, such as Hans Eworth’s Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses (Fig 7). As dead relatives could not sit for paintings, allegories made use of face patterns and copying from pre-existing portraits. This painting, while a family portrait of sorts, is in fact a propaganda piece designed to cement Elizabeth’s legitimacy and emphasise her relations as the daughter of Henry VIII and sister to Edward VI and Mary I.

Elizabeth’s rule was constantly questioned, being declared a bastard following her mother’s execution. Before Henry’s death, he restored her to the line of succession, only to be removed by Edward on the grounds of legitimacy and finally restored again in Mary’s will. As patriarch of the family, Henry sits on a golden throne atop a carpeted platform, representing the royal heritage that allows his children to inherit the throne. He sits beneath a richly decorated canopy that only covers himself and a little of his son Edward, who kneels at his feet on the right side. Above Henry is the royal coat of arms and surrounding him are emblems of the Tudor dynasty. Henry passes the sword of justice to Edward, signifying that he is his heir apparent. Edward wears the livery collar, a badge of allegiance to the Tudor crown.

Philip and Mary, the Catholics, are situated on the left side of Henry, while Elizabeth and Edward, the Protestants, are situated on the right (literally the ‘right side’). The Catholics anachronistically wear dark clothes from the 1550s, while the Protestants wear brighter, vibrant colours. Personifications of Roman mythology join the family towards the edges of the painting, situated on either the Catholic or Protestant side, acting as allegories for the reigns of each monarch. Mary’s reign is characterised as violent and warmongering through armour-clad Mars, God of War, who, with lance and shield in hand, appears to sprint towards the Protestants. This is symbolic of Mary’s infamous burning of Protestants and their loss of Calais through war and, for the second painting, represents the Spanish Armada that Philip would later send to England.

Conversely, Elizabeth’s reign is characterised through Peace and Plenty, the former standing upon the sword and shield of war, wearing a Renaissance-Classical fusion dress. Elizabeth leads Peace by the hand, while Peace holds an olive branch in the other. Plenty follows behind holding a cornucopia of possibly imported fruits thanks to Elizabeth’s trade and empire, and she carries Elizabeth’s train in her other hand. These two feminine figures being led by the female queen presents her as a strong female leader, an element that needed to be emphasised in a society where women were not regarded as natural leaders. Henry sits between the feuding religions, having created the Church of England to break away from the Catholic Church, but still being a Catholic at heart. In the background through the archways is Catholic Rome on the left, with St. Peter’s Basilica, and Protestant London on the right, with the pillars of Whitehall Palace just visible by Peace’s head.

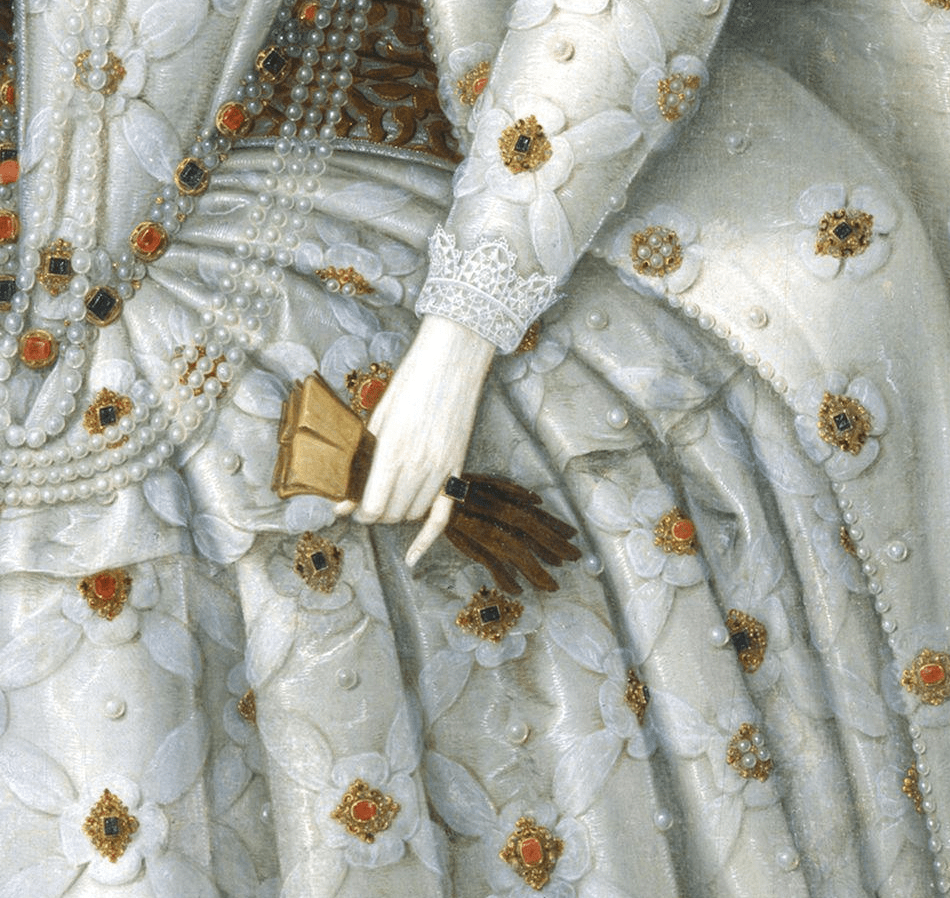

The most noticeable change between the two paintings is the figure of Elizabeth. In the first painting (Fig 8), she wears a brown dress reflective of 1570s fashion, the decade when the painting was commissioned. In the second painting (Fig 9), unlike most other figures, her outfit has been updated to the current fashion. This dress is one that appears in many portraits of hers, particularly The Ditchley Portrait, which appears to have become a pattern receiver of the latter The Family of Henry VIII. Elizabeth’s face appears much whiter compared to the original, reflecting how she wore white makeup after surviving smallpox to cover her scars.

Elizabeth’s Dress, Edward and Peace

On Elizabeth’s left side is her younger brother, Edward VI. Being only nine when he ascended the throne, Edward is painted small, only coming up to Elizabeth’s elbow. In the second painting, however, Edward is painted even smaller, this time standing rather than kneeling, but not gaining any height. His pose is less dynamic too, making him appear as merely a background character, not the king that he was before Elizabeth. Elizabeth is positioned further to the front than all her family members.

In Edward’s case however, she stands in front of him, almost elbowing him out of sight. While the second artist chose to paint Edward with brighter colours than his Catholic siblings to match the other Protestant, he merges into Elizabeth’s dress, making him hard to spot. Although Edward and Elizabeth got along during his reign, Edward wrote Elizabeth out of the line of succession in favour of Lady Jane Grey, claiming Elizabeth to be illegitimate, among other reasons. Elizabeth covering Edward may signify a wish to obscure him as revenge.

Similarly to Edward, Peace has also lost height in the second painting, going from being the tallest figure to just short of Elizabeth. All these aspects make Elizabeth more prominent, with the audience’s eye always being drawn to her.

Elizabeth’s Hands

A small yet significant difference in the later painting is Elizabeth’s hands. In both paintings, she holds the hand of Peace, leading her into the picture. In the original painting, Elizabeth’s right hand points towards the two Roman personifications to further emphasise what she provides for England.

In the latter painting, however, the pointing hand is changed to a hand holding a glove, as if she has removed it to more intimately hold Peace’s hand. Elizabeth was famously enamoured with her extra long, pale fingers, which she used to her advantage at political encounters, extending them for others to kiss and marvel at.

She is often depicted as holding a glove as opposed to wearing them, such as in Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder’s The Ditchley Portrait (Fig 11) and The Wanstead Portrait. Elizabeth’s real gloves accentuated her fingers’ extreme length, with stitching and padded fingertips elongating them even further.

While her hands had always been a subject of admiration, the latter painting adding this change shows how the queen utilised them more and more as her reign progressed. One will notice that jewels and rings adorn her fingers less and less in her portraits as time goes on and more focus is drawn to the bare hand.

The Figure of Plenty

In the original painting, Plenty holds a cornucopia of ripe fruit, flowers and vegetables, while her peplos (or palla, as this is the Roman personification) exposes her breast, as if to provide sustenance to a baby. At this time in the 1570s, Elizabeth was still young, fertile and available to marry, as was also depicted in George Gower’s Hampden Portrait (Fig 14) with the tree behind her bearing fruit, similar fruit which is seen in Plenty’s cornucopia.

Once Elizabeth’s youth began to fade, and the Cult of the Virgin Queen was established, the latter artist may have thought it appropriate to cover Plenty’s breast to draw less attention to the fading fertility of the queen and focus instead on the cornucopia that represented the abundance of produce that Elizabeth brought to the realm.

Two fruits are positioned in such a way in both paintings that they resemble breasts, further hinting at sustenance and femininity.The latter painter also takes the opportunity to update Plenty’s dress, changing the Romanesque toga to a more Tudor-style garment. Finally, Plenty’s gaze has shifted from Mars in the first painting to Elizabeth in the second, further emphasising that the focus should be on the current queen, rather than monarchs bygone.

A New Face

Fig 14: detail of Plenty in de Heere’s ‘Allegory’.

Fig 16: detail of Elizabeth I and the fruit tree in Steven van der Meulen’s ‘The Hampden Portrait’, 1567.

On the left of the portrait we see a new face, which is very easy to miss. He appears from the chest up within a small arch situated in Catholic Rome. It is unknown who this person is, however many theorise that it is the Tudor family fool, Will Somers. Somers had appeared in many Tudor family paintings previously, prominently in The Family of Henry VIII, which features the fool within a similar archway. His inclusion suggests that he was well-loved by the Tudors, having entertained during the reigns of Henry, Edward, Mary and been present at the coronation of Elizabeth. He could even have been regarded as a member of the family.

Alternatively, the face could represent another person involved in the production of the painting, such as the commissioner or the painter themselves. The figure faces forwards and gazes at the audience, similarly to the Tudor figures, but unlike the Roman personifications, suggesting that the figure is, at least, a real person. Finally, this new face balances out the overall amount of faces in the painting. There are now four people on each side of Henry, and that area naturally had room for a new person, unlike the other side of the painting, which is taken up by Plenty’s cornucopia. Therefore, this person may not have particularly supported the Catholics, but only appeared where he could physically fit.

Conclusion

Overall, the two “Family of Henry VIII” paintings are almost indistinguishable, but, on closer inspection, we can see subtle changes that coincided with the way that Elizabeth wanted her family to be remembered and, most importantly, how she wanted to be perceived and remembered.

Written by Annon Ford

Bibliography

Amgueddfa Cymru. “The Family of Henry VIII: an Allegory of the Tudor Succession.” Art Collections Online. Publishing date unknown. Accessed Sept 24, 2024.

Apostu, Corina. “The Hands of Elizabeth I with Corina Apostu.” Interview by Tudor Extra. Tudor Extra. Jan 25, 2024.

Aubery, L, and Seigneur de Maurier. Mémories pour servir à l’Histoire de Hollande. Paris, 1680. Quoted in Roy Strong, Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

Auerbach, Erna. Tudor artists: a study of painters in the royal service and of portraiture on illuminated documents from the accession of Henry VIII to the death of Elizabeth I. London: Athlone Press, 1954.

Belsey, Catherine. “Richard Levin and In-Different Reading.” New Literary History 21, no. 3 (1990): 449-456.

Chestnutscoop. “In Defence of MMD Transformative Artists- A Justification On Why MMD Renders Should Be Respected as ‘Valid Art’ and the Impossible Pursuit of ‘Original Art’.” DeviantART post. Posted by “Chestnutscoop.” Sept 10, 2023. Accessed Sept 24, 2024. https://www.deviantart.com/chestnutscoop/art/In-Defence-of-MMD-Transformative-Artists-981509726.

History Calling. “HIDDEN MESSAGES within famous painting of Henry VIII and his children | The Family of Henry VIII.” YouTube video, 00:00. Posted by “History Calling.” Sep 30, 2022. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eiq5QomXJ5E&list=PLLSjVq5Qtb0Eh4LJzcqLO_ayueqJt8ao-&index=7.

History Calling. “SECRETS OF THE IMPOSSIBLE TUDOR PORTRAIT | Art history documentary | Tudor history documentary.” YouTube video, 00:00. Posted by “History Calling.” Aug 26, 2024. Accessed September 24, 2024.

Hopkins, Lisa. “In a Little Room: Marlowe and The Allegory of the Tudor Succession.” Notes and Queries (2006): p. 442-444. Accessed Sept 24, 2024. https://academic.oup.com/nq/article-abstract/53/4/442/1138941?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=true.

Hui, Rowland. “Clowning Around- The Portraits of Will Sommers.” TUDOR FACES: Observations and Musings on Tudor Portraiture and Personalities (blog) June 6, 2013. Accessed Sept 30, 2024. https://tudorfaces.blogspot.com/2013/06/clowning-around-portraits-of-will.html.

Strong, Roy. Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

WPR Agency. “Tudor Succession at Sudeley Castle.” YouTube video, 00:00. Posted by “WPR Agency.” July 18, 2017. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bo_VwrT1tSA.

Yale Center for British Art. “Art in Context: Lisa Ford on “An Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII.” YouTube video, 00:00. Posted by “YaleBritishArt.” May 16, 2012. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vp0mtLONkUk.

Yale Center for British Art. “Conserving “An Allegory of the Tudor Succession” – Phase 1.” Yale Center for British Art. Publishing date unknown. Accessed Sept 24, 2024.

https://britishart.yale.edu/conserving-allegory-tudor-succession.

Images, in order of appearance

Holbein the Younger, Hans. Portrait of Henry VIII. 1537. Oil on panel. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/henry-viii.

van Dyck, Anthony. Charles I (1600-1649). 1635. Oil on canvas, 84.4 x 99.4 cm. Buckingham Palace, London.

https://www.rct.uk/collection/404420/charles-i-1600-1649.

de Heere, Lucas. The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession. 1572. Oil on panel, 131.2 × 184 cm. Sudeley Castle, Cheltenham. https://sudeleycastle.co.uk/news/allegory-tudor-succession-painting.

Unknown. An Allegory of the Tudor Succession: The Family of Henry VIII. 1590. Oil on panel, 114.3 × 182.2 cm. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15706750.

van Leemput, Remigius, Hans Holbein the Younger (original). The Whitehall Mural. 1667. Oil on canvas, 88.9 x 99.2 cm. Kensington Palace, London. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405750/henry-vii-elizabeth-of-york-henry-viii-and-jane-seymour.

Unknown. The Family of Henry VIII. 1545. Oil on canvas, 144.5 x 355.9 cm. Hampton Court Palace, Molesey. https://www.rct.uk/collection/405796/the-family-of-henry-viii.

Eworth, Hans. Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses. 1569. Oil on panel, 62.9 x 84.4 cm. Windsor Castle, London. https://www.rct.uk/collection/403446/elizabeth-i-and-the-three-goddesses.

Gheeraerts, Marcus, the Younger. Queen Elizabeth I (‘The Ditchley Portrait’). 1592. Oil on canvas, 241.3 x 152.4 cm. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Coronation Glove, Elizabeth I. 1559. Dents Glove Museum, Warminster.

van der Meulen, Steven. The Hampden Portrait. 1567. Oil on canvas, 196 x 140 cm. Private collection. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Elizabeth_I_Steven_Van_Der_Meulen.jpg.