Power or Pressure? Exploring whether Cosmetic Practices throughout History have Granted its Users Agency

Introduction

Throughout history, women have utilised cosmetic practises to beautify themselves, adorning their appearances. Historiography and societies have viewed these actions typically as a product of patriarchal influence, reducing cosmetic practices as being dictated by the male gaze. However, this article will reflect how this has not always been the case. Cosmetics have actually been consistently used by women especially to grant themselves agency. By focusing on transgender-women (trans-women), black women and cisgender-women (cis-women), cosmetics will instead be reflected as resisting historical beauty ideals.

To fully appreciate agency, this article will implement historian Lynn M. Thomas’ idea of ‘neoliberal agency’ to reject reducing subject agency into a simple afterthought. Thomas interprets neoliberal agency as reflecting one’s rational intentions, free will and a sense of control over their own actions. This will be explored through case studies that illuminate the impact of gender and race on beauty, and primary sources such as anecdotes to emphasise the intimate and personal element of cosmetics. In addition to other adornments and beauty treatments, this article will focus on the historic use of makeup to compare how differing cosmetics have repeatedly bypassed imposed beauty standards. This evaluation across different time periods, cultures and places will ultimately reveal the overall power of women and beauty to resist mainstream pressurising ideals. In turn, this article will illuminate the significance of beauty throughout history, in how it reflects the agency that women gain from cosmetics.

Cosmetic Practices, and the Gender Identity of Trans-Women

To reflect the ability of cosmetic practices to offer users agency, an exploration of makeup is crucial, in particular how it has been used by transgender women. In today’s modern society, Professor Karla M. Padron has delved into this, interviewing two transgender Latina makeup artists in 2020. Discussing with Brenda Del Rio Gonzalez and Renata Garcia, Padron sheds light upon the impact and significance of the transgender beauty pageant. Contestants and participants beautify themselves through this communal act, using makeup and outfits as cosmetic practices to act as a form of identity reclamation, thus empowering trans-Latina women.

This conscious use of makeup to adorn their faces aligns with Thomas’ desire for a reflection of neoliberal agency, due to the international beautification of Gonzalez and Garcia, as well as their community of trans-Latina women. Through the deliberate expression of their gender identity through their makeup and cosmetics, these women embrace their Latina-transgender individuality and therefore their neoliberal agency. This is particularly important in the face of past colonial and prejudiced interpretations of Latinas. Sociologist Albert Memmi’s statement from 1957 sought to undermine them, stating that the “body and face of the colonised are not a pretty sight,” due to the impact of “historical misfortune.” Padron’s intimate and personal work alongside Gonzalez and Garcia therefore reflects an attempt towards the modern decolonisation of this prejudiced notion, through communal and individual use of cosmetics. Ultimately, the resistance and active, neoliberal agency of trans-Latina women is illuminated through cosmetic practices.

To contrast with this modern example, it is important to also highlight how trans-women in the Byzantine Empire utilised cosmetic practises and adornments as a form of outward gender expression. Using historian Roland Betancourt’s work surrounding this subject reflects the continuity of trans-women’s cosmetic practices. Betancourt’s analysis uses medieval, religious anecdotes and translations from the middle of the Byzantine Empire. Their individual use of adornments is displayed, especially through Betancourt’s focus on the Roman emperor Elagabalus. In accounts by her contemporary, Dio Cassius, Elagabalus is described to have identified as female, in an attempt by Cassius to defame the ruler. In these sources, Cassius discusses how Elagabalus would wear wigs, apparently to resemble a female sex worker, while also shaving her face and painting her eyelids, to “look more like a woman.” The purposeful use of beauty and cosmetic practices to outwardly and tangibly express Elagabalus’ desired gender identity is clear.

The importance of reflecting Elagabalus’ neoliberal agency is intensified by Cassius’ desire to weaponise her cosmetic practices. Despite this attempted vilification, Elagabalus beautifying herself to appear more feminine highlights her calculated intentions, emphasising her free will and neoliberal agency. Betancourt also aids Thomas’ aim of historicising agency by unveiling transgender absences throughout historiography and incorporating this into histories of beauty. Although contemporary Byzantine accounts viewed trans-women as “womanish creature[s]” and were dismissed by traditional medieval historians as falsified stories of the Christian mind, Betancourt frees these individuals from the restraints of this mainstream denial.

Trans-women throughout history therefore utilise intentional outward cosmetic practises to enable the physical illumination of their gender identity, and thus exhibit their neoliberal agency. Historic gender binaries are expanded as a result, thus importantly ingratiating trans-women’s beauty and personal histories into historiographies.

Black Women, Skin Lighteners and Phenomenological Cosmetic Practices

This section will explore how modern black women have used different methods of beautification, especially focusing on skin lighteners and phenomenological cosmetic practices. Thomas’ work analysed how black women have used skin lighteners as cosmetic practises in South Africa and Kenya in the late twentieth century, using adverts and magazines to reveal this. She discussed how these were used prominently by schoolgirls to increase their status, image and beauty, linking lightened skin to greater privilege. Political contemporaries viewed this as exemplifying racist and white beauty ideals, believing that it reinforced black women’s insecurity and embarrassment towards their appearance.

Although this argument would present cosmetic practices for black women as a tool of conformity, submitting to societal and racial pressure, their ultimate independence and agency takes precedence. The schoolgirls’ autonomous usage of skin lighteners instead framed them as shaping their own image and status as they wish. Additionally, Thomas used the example of South African kwaito artist Nomasonto Maswanganyi, famously known as Mshoza, to emphasise the international use of skin lighteners to demonstrate neoliberal agency. Mshoza infamously used skin lighteners for her own cosmetic use to alter her “outside” appearance due to her lack of self-esteem. Although one may see this as more evidence of giving in to beauty pressures, these purposeful cosmetic practices to elevate one’s status or confidence actually reflects their neoliberal agency. Historiography should refrain from solely viewing skin lighteners as a racist threat, victimising those who choose to use them. Framing skin lighteners as liberal and self-affirming, therefore reflecting neoliberal agency, is important to appreciate multifaceted intentions and interpretations of cosmetic practices.

To explore further how cosmetic practices have been used by black women in the twentieth century to assert their agency, Professor Allison Vandenberg analysed their phenomenological beauty practises in the United States. Detailing individual experiences to undertake this analysis and look at how “intersectional aspects of women’s identities” impact their cosmetic and beauty practices, Vandenberg’s exploration stands out from existing historiography. This sees cosmetic practices as stemming from social pressure, similar to the political activists discussed by Thomas in terms of skin lighteners. Vandenberg utilises the example of Cheryl Browne, the first black woman to compete in the Miss America national beauty pageant competition in 1971, to reinforce her argument. She views Browne as demonstrating the passive adoption of white ideals, through her light eyes and straightened hair, contrasting against how she later praises the embracing of black women’s own natural beauty.

However, Vandenberg overlooks the possibility of incorporating Browne into her overall argument of how black women, but also women in general, have utilised cosmetic practises, for example through their nails, hair, and makeup, to adapt to societal pressure. She linked this to feminist writer Sara Ahmed’s view that “what we ‘do do’ affects what we ‘can do,’” thus seeing how women shaping their own beauty and appearance impacts their prospects, in life and society. This therefore reflects black women as having the rationale and intention to decide their own actions to beautify themselves. With Browne implementing cosmetic practises to further herself within the pageant, this therefore reflects her neoliberal agency.

Ultimately, both examples of black women’s use of beauty in the twentieth century reflect how reducing their actions to simple expressions of white ideals of beauty is misleading and dangerous. Instead, international cosmetic practices are able to illuminate the neoliberal agency of black women, across the modern United States, South Africa and Kenya especially.

Cosmetic Practises and the Face of Cisgender Women

By exploring the makeup of cis-women in Europe, the ability of cosmetics to illuminate their neoliberal agency will be revealed, especially focusing on the beauty of the face in the eighteenth century. Academic scholar Lynn Festa has analysed the differing makeup between English and French women, particularly using the views of contemporary men. Through their writings and anecdotes, Festa notes their criticism of the promiscuity and sensuality of makeup on the female face.

In terms of makeup practised by English women, especially seeing the significance of the colour red, male writers viewed this as “fish[ing] for lovers as men bait for mackerel,” connecting a woman’s personality to her cosmetic practises. Similarly, it is commented on by male contemporaries how the makeup of French women “aim at the conquest of hearts for the purpose of enslaving” men, thus revealing how men of both nations viewed the manipulated beauty of their women as encapsulating their immorality on their faces. However, neoliberal agency through makeup is instead reflected, despite the misogyny rife in these accounts, through the intentional sirenic nature of French and English women’s makeup to exert power and influence over men. Despite this, Festa’s analysis dangerously similarly villainises French and English cosmetic practises, blaming it as blurring national differences, by “denaturing” female features, assigning fault to their beauty.

The similar significance of the European female face and makeup is demonstrated through an exploration of physiognomy in Victorian beauty manuals in England. Historian Sarah Lennox has discussed this, viewing the guides as promoting how the nature and soul of a woman was reflected upon their face. Thus, men were allowed to label women as immoral, based on a tangible visualisation of their sensuality. Again, this reinforced the misogynistic notion of male contemporaries judging a woman’s personality by their face, attempting to control, restrict and undermine their use of cosmetics. Men in Victorian England judged cosmetic practices as being unable to mask the true nature of a woman, seeing makeup as a disguise, believing that no “mysteries of art can ever make [a woman’s] face beautiful” if they deemed it as ugly and sinful.

Despite this, beauty products and recipes were still advertised in manuals to promote how natural treatments were able to aid the skin, complexion and hygiene to alter a woman’s appearance. This would grant women the ability to control and manipulate their own presentation and public character through treatments to the face. Therefore, women could reclaim neoliberal agency through deliberate beautification. Although the misogynistic religious context attempted to subdue women, they were ultimately able to reclaim power over their facial appearance through their free will to intentionally practise beauty treatments.

European women in the eighteenth and nineteenth century are therefore reflected to have been subjugated to the ideals of facial and feminine beauty under the patriarchy, fearing their promiscuous power as a threat to masculine dominance. However, through the deliberate use of cosmetics of makeup and beauty treatments, women were able to resist this, exhibiting their neoliberal agency.

Conclusion

This article has explored how cosmetic practices throughout history are able to reflect women’s neoliberal agency across a variety of locations and time periods. Cosmetics have been revealed to aid expressions of gender identity and help resist patriarchal and racial ideals of beauty. The female users of cosmetics are continuously seen to exhibit rational control over their appearance and presentation by using beauty products. Makeup, adornments and beauty treatments are ultimately able to intentionally adorn and beautify women, meeting Thomas’ desire for neoliberal agency to reflect subjects as active in historiography. Exploring the fragmented histories of these individuals ultimately allows for a greater emphasis on the importance of changing meanings of agency, to reveal different and more nuanced lines of historical narratives, as Thomas wishes. Thus, the obscured histories of women and cosmetic practices ultimately demonstrates their neoliberal agency and the importance of it throughout history.

Written by Piper Hedges

Bibliography

Images

Browne, Cheryl. 1971. Photograph. https://x.com/mrbdj95/status/1007336530254467072.

Elagabalus. 18th century. Wall painting. Castle Forchtenstein, Burgenland, Austria. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elagabalus_Forchtenstein.jpg.

Rowlandson, Thomas. Six Stages of Mending a Face, Dedicated with respect to the Right Hon-ble. Lady Archer. 1792. Hand-coloured etching, 27.4 × 38.4 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/392701.

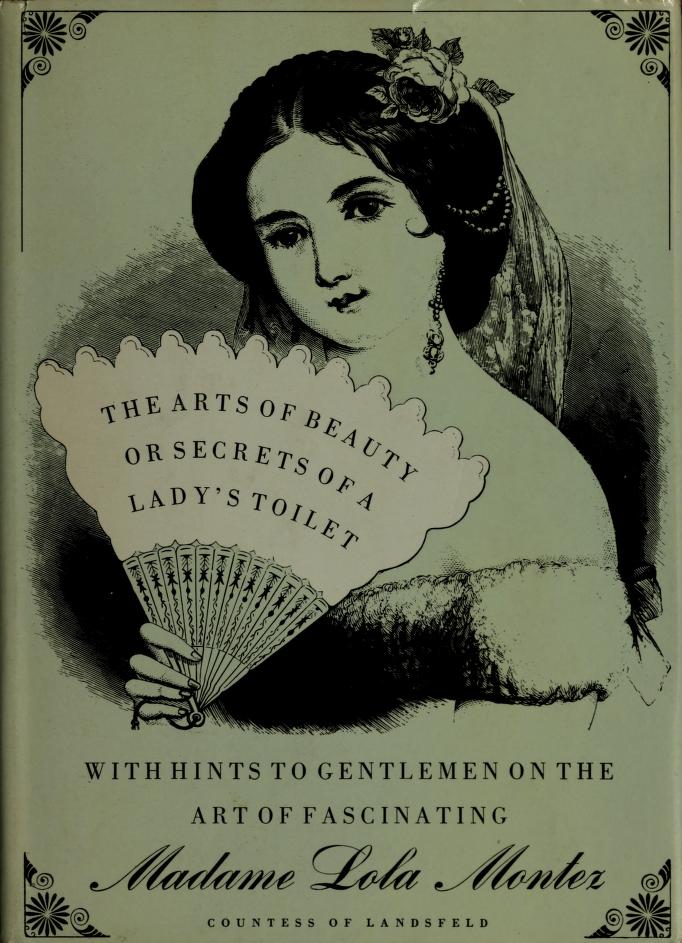

Montez, Lola. The Arts of Beauty: Or, Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet, with Hints to Gentlemen on the Art of Fascinating. New York: Ecco Press, 1858.

Sources

Betancourt, Roland. “Where Are All the Trans Women in Byzantium?” In Trans Historical: Gender Plurality Before the Modern, edited by Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, Anna Kłosowska, 297-321. Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, 2021.

Festa, Lynn. “Cosmetic Differences: The Changing Faces of England and France.” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 34 (2005): 25-54.

Lennox, Sarah. “The Beautified Body: Physiognomy in Victorian Beauty Manuals.” Victorian Review 42, 1 (2016): 9-14.

Padron, Karla M. “To Decolonise is to Beautify: a Perspective from Two Transgender Latina Makeup Artists in the US.” Feminist Review 156-162, 128 (2021): 156-162.

Thomas, Lynn M. “Consumer Culture and ‘Black is Beautiful’ in Apartheid South Africa and Early Postcolonial Kenya.” African Studies 78, 1 (2019): 6-32.

Thomas, Lynn M. “Historicising Agency.” Gender and History 38, 2 (2016): 324-339.

Vandenberg, Allison. “Toward a Phenomenological Analysis of Historicized Beauty Practices.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 46, 1 & 2 (2018): 167-180.

This was such an interesting read!

LikeLike

Very interesting, never really thought about it in this way

LikeLike