Angry, Fat and Cross – the Unmarried Woman in Early Modern England

Introduction:

Unmarried women occupied a common, yet unique, position in Post-Mediaeval society. To be unmarried meant to be partially socially and financially independent, but also to waiver certain social rights and privileges that were ordinarily only available to married women. A woman’s ability to live independently was heavily reliant on her family, as well as her personal financial and social standing; an upper-class woman was more able to remain unmarried or widowed than a working-class woman. The stereotype of the widow (elderly, destitute, lonely and haggard) is one that is inherited from the Post-Mediaeval period. Widows of the Early Modern period were commonly viewed as being outside of community social circles and often associated with cunning-folk or witchcraft. The lack of poor-relief in some parishes, plus the drain that an elderly widow would have been (and been seen as) on community resources often lead to ostracisation and resentment. A good example of this stereotype is “Sarah Green, a widow… [who] did at last sell herself, body and soul, to the Devil” – her widowhood and alignment to the devil are inextricably linked. By the eighteenth century, stereotypes of widows appear to have moved away from witchcraft and supernatural evils towards more earthly transgressions, such as murder, science and gambling. As superstitions around widows declined and they were therefore viewed as ‘safer’ by the populace, they also became the subject of satire in both print and the wider media.

Widow Waddle – A Woman of Substance:

Urban, working-class widows were a common source of mockery and satire in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, much more so than their upper-class counterparts. Characters like that of Widow Waddle, published by Tegg in 1807 (Figure 1), are found across prints, plays, novels and all forms of popular media at this time, and indeed even overseas (further examples of these characters can be seen in the appendix). The urban landscape was viewed as a vice-filled and dangerous place, especially for unmarried women – rural life and the countryside was deemed a far safer place for them. The urban elites disliked unmarried women due to (as Peters puts it) “the [supposed] insatiable female sexual appetite and also because of a more general fear of the masterless”. Widow Waddle, who ends her journey by murdering her new husband with a stool in the tripe and trotter shop she owns (Figure 1), represents a stereotypical comedic view of widowhood for this period: she is angry, fat and cross; owns her own business, but admittedly sells lower quality cuts; marries, but only to later end the relationship – this time through murder. She is, of course, a caricature. She is also, importantly, masterless (she sees to that) and violent. Widow Waddle represented what, according to an eighteenth-century mind, could and would happen to a woman if she was not under a man’s control. Nevertheless, Widow Waddle and her compatriots of the widow-themed satirical print world are a useful tool to offer us a window into the lives of underrepresented and working class single women.

It is important to note that Tegg’s Widow Waddle is accompanied by a ballad – her story is designed to be sung (Figure 1). Ballads played an important role in Early Modern English society; they were used to entertain, for news dissemination and as a method of exploring the complex themes and social issues of the day. Widow Waddle straddles two of these themes. She is both an amusing tale, one that could be sung in rowdy pubs on a cold winter’s night perhaps? But she is also a warning to Early Modern men not to let women get out of control, and to beware of ‘masterless’ women.

It is not explained whether Widow Waddle has inherited the shop from her previous late husband, if she bought it in her own right or if it was hers before marriage. However she came by the shop, the fact is she owns one and this is both impressive and threatening to Early Modern audiences. A woman running a shop was viewed as independent (and therefore dangerous) and perhaps most worryingly, masculine (even more dangerous!). This masculinisation is further reinforced by the unwomanly products of the shop itself – tripe and trotters. Widow waddle is both feminine and masculine – she usurps what is seen as ‘the natural order’ of marriage and family and becomes her own master. Could this masculinisation be manifesting the contemporary (probably male) audiences’ anxiety surrounding capitalism, single women with independent power and the supposed threat they posed to ordered Civil Society?

The Widow of the Stage:The widow of the stage was no less colourful or prolific, metaphorically speaking, than her printed kinswoman. Both ballads and plays encouraged young men to marry widows for their money; the widow often being portrayed as rich, desperate and acting the part of a ‘get-rich-quick scheme’. Widows acted like ‘MacGuffins’ – being used as plot devices for the male characters; Nickerson argues that they often lacked coherent motives or deep personalities, being altogether rather two-dimensional characters. Hanson more persuasively argued that the widows of Early Modern theatre have lively personalities: “haughty and hypocritical… chaste but wooable…” . A chief example of this, for Hanson, being ‘Taffatta’ from Ram-Alley (published in 1608 and well known for subverting typical gender roles of the period), known for her financial and sexual freedoms. However, both agree that the widows represented in theatre are almost exclusively rich, and nearly always wed by the end of the play. Hanson adds depth to this notion, arguing that these representations should be viewed as a product of the new way in which money was being perceived – as both commodity and tool, rather than a luxury item. The creation of financial debt in 1693 and the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 revolutionised the way in which people interacted, conceptualised and thought about money. England was rapidly becoming a mercantile nation and the use of widows as sources of financial gain within theatre only represents this new lust for money and the societal want to acquire it – in a world where everything was for sale, women were by no means exempt from being exchanged like currency.

Marriage in Early Modern England:

This prevalent, misogynistic view of widows in fact reveals the unseen power that they held in Early Modern England. In a society where over half of marriages ended by their 25th anniversary, widows were a common and well-known sight, even if an unpopular one at times. However, this ‘army’ of widows played an important part in urban society, taking on the roles of landladies, creditors, tax and ratepayers, householders and philanthropists. In an age when society was still held by the concept of coverture (the idea that women were bound to men and, specifically here, the idea that her financial assets would become his upon marriage), it was only wealthy women who could afford to be self-supporting, or have a marriage contract drawn up by the family to maintain her own finances and property. Thus, it is often only the wealthy élites that are present in the archaeological record, while the working classes are either absent or satirised in material culture.

While marriage was an economic necessity as well as a social standard, Peters argues that a household headed by a single-woman “was perceived as a possible, if not necessarily ideal, solution” to ‘modern’ urban life. Financial affairs of women were very limited, especially before the establishment of the Bank of England and the opening of financial spheres of trade. Many bequeathments in wills required daughters to marry in order to be released. Only later was a move towards age restrictions seen, and even then traditionally and commonly only entitled a widow to one-third of her husband’s estate. These however, would have only been a concern of the elites, whose widows would have had the financial means to invest and be self-sufficient, as well as having a lot more to lose; Smith argues that only 12% of widows would have been self-supporting. These widowed élites were represented and viewed very differently by the media and society than their working-class counterparts (Figure 2). This class inequality affects how material culture was made and is interpreted within Historical Archaeology.

Marriage was not the only form of economic gain available to the widows and spinsters of Early Modern England. Women were often seen as more deserving of financial aid from the church and community, thus were more commonly on ‘regular relief’, especially after the 1601 Poor Laws came under stress in the 18th century; whether they got it or not, or how the community felt about it, was a different matter. Elsewhere, lotteries and independent mercantile ventures, perhaps more genteel than that of Widow Waddle’s tripe and trotter shop, may also have represented a great proportion of income for single women. The independence of personal ventures may have outweighed the lack of financial security that came with marriage.

‘Why do Only Fools and Widow’s Work?’

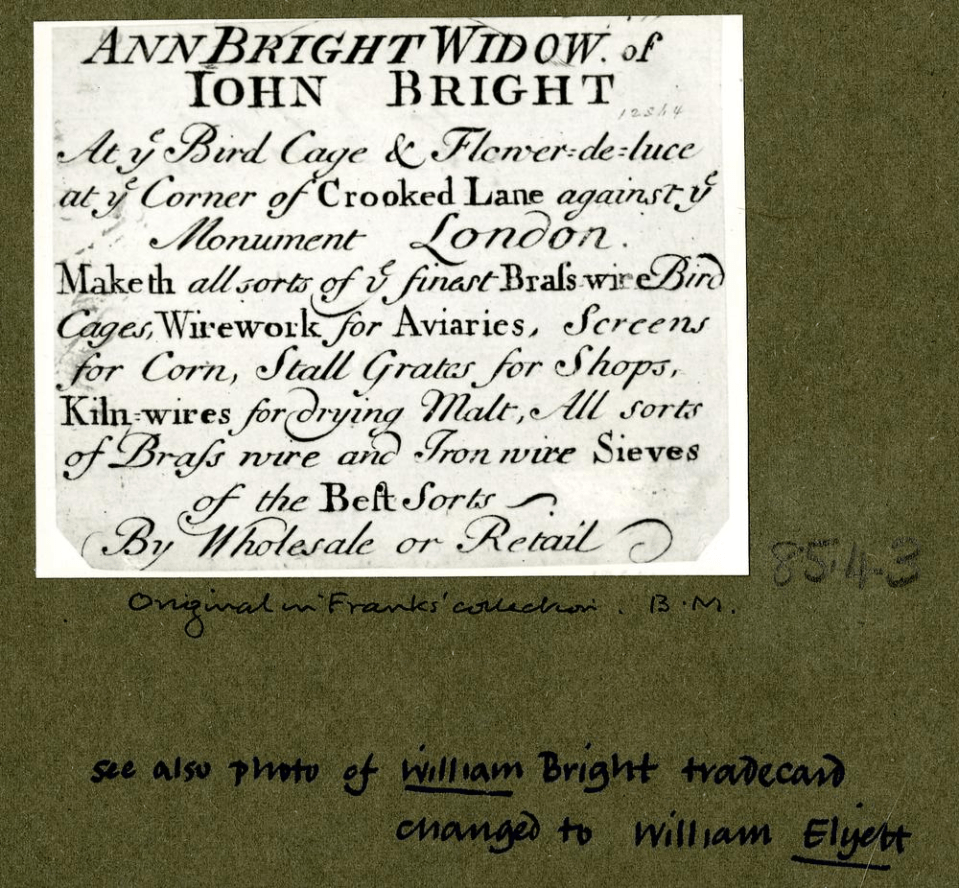

A woman running her own business was not a complete caricature; material culture informs historical archaeology of this. One such woman found in the material record is Anne Bright, who sold brass and iron wirework products in London (Figure 3). She is introduced as the widow of John Bright (Figure 3), which suggests that she was either using her late-husband’s name to legitimise her business, herself or the quality of her goods, or to try and sway sympathy from the reader of the tradecard. Even when she is of somewhat independent means, it suggests that she is still not quite her own person. Given that she is located against the statue (Figure 3) and not in a physical shop, it is safe to assume that Widow Bright is at the lower-end of the financial standing of society. The aspects of Widow Waddle’s caricature are evident though, as Widow Bright is selling hand-made wire frames, aviaries and other utensils (Figure 3) – a far more genteel and feminine industry for a widow, safely removed from both trotters and tripe.

Widows within business practices are found elsewhere within the material record. In c.1835-c.1840, Widow Welsh emerges in an ‘advert’ for pills bearing her own name, that appears to promise the reader that they will provide them a new husband – the process of which is not explained (Figure 4). Importantly, Widow Welsh conforms to the same stereotype as Widow Waddle: she is pox-marked (ugly); overweight when compared to the other characters (fat); is planning (apparently) to remarry; is involved with mercantile practices and money. Widow Welsh contrasts Widow Waddle as she is not cross – quite the opposite, she seems to be quite pleased with her rather debonair, new man (Figure 4). This advert is, of course, a satire. It plays on contemporary anxieties surrounding new medicines, morality and the role of men and women and their sexuality. Widows in urban centres would have been at least somewhat, if not entirely, dependent on poor relief which, in the decades leading up to the Poor Law reforms of 1834, was already struggling under populations it was simply not designed for.

The Lottery:

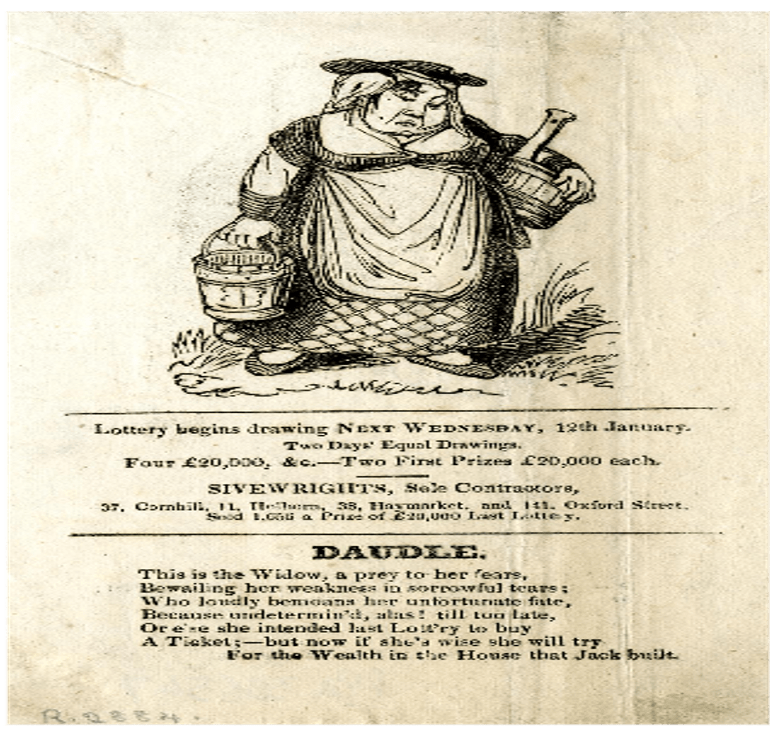

Lottery prizes also paved the way for single-women to have financial independence in Early Modern England. One advertisement for a lottery in 1818 aimed itself directly at widows and single women, and offered two prizes of £20,000 (Figure 5); worth about £1.15million today. The sheer value of this sum can only be appreciated if matched to the purchasing power of the pound in 1818, or by the percentage of income that it would have represented, as argued by Floud (2016). At the equivalent of 133,333 days’ wages – or over 365 years – for a skilled tradesman, this money would have been, quite literally, life changing. No immediate records could be found so, without this piece of material culture, archaeologists would not be aware that this was an option for widows and single women, nor that a working-class widow could, in theory, win such a vast sum from a lottery.

Conclusion:

Without this material culture informing Historical Archaeologists about this changing attitude towards widowhood, and insight into the day-to-day lives of the impoverished, it would be stranded in the realms of estimation. The mundane and personal lives of the poor have always been absent in the historical and archaeological record; perhaps due to a lack of material wealth, poorly built housing or a lack of written accounts from the people themselves. Without the aid of documentary evidence written from the wider society’s perspective (and usually by those who could afford it), historical archaeology would not have as much of an insight into these unrepresented groups as it does. It would be left with the understandings garnered from the minimal archaeological evidence and slithers of historical records from parishes and institutions.

In conclusion, the stereotypes faced by widows in printed media run deep throughout the urban world. They were faced by the poorest widows, who were depicted time and time again as ugly, angry, fat and cross (further examples in the appendix). The upper echelons of society were far more unlikely to face such ridicule, often being revered in a demure and elegant manner, far removed from society’s ills. As was discussed, the reality of a widow’s life was harsh, and often they were destitute and relied on pitiful and strenuous poor relief – their personal stories and feelings will likely forever remain a mystery to archaeology. The urban poor remain marginalised and unrepresented in historical archaeology, due to their poor preservation and research. Without material archaeological evidence, the insights into the lives of the unrepresented would remain an enigma. Equally however, without the unrepresented leaving a hole in research, the material culture would be left voiceless. The two must work in tandem; research and materiality combining to tell the stories of widows and single women in Early Modern England. Historical archaeology has offered a window into the lives of these women and the struggles, trials and tribulations they went through – just as much as inequality has offered a window into historical archaeology.

Written by Tomo Ollivier

Bibliography

Anonymous (1760). Tradecard of Anne Bright, Widow of John Bright. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_Heal-85-43. [Accessed 18 December 2023].

Anonymous (1762). A Most unaccountable relation of one Miss Sarah Green, a widow, living at Beesly, in the county of Worcester, who following the wicked practice of witchcraft for some time, did at last sell herself, soul and body, to the Devil for fourteen years, and when the time was near expired, she being very sad, sent for her two children and some ministers, and discovered the matter at large, desiring their prayers and good endeavours for the recovery of her soul, which was performed accordingly, though to no purpose; for upon the last day of the term, about midnight, April ye 14th, 1747, she was suddenly struck dead by an infernal spirit in the shape of a bear, to the terror and astonishment of all then present. With the heads of a sermon suitable on this occasion. United States: Early American Imprints.

Anonymous (1783). Emma Corbett. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1902-1011-7373-. [Accessed 18 December 2023].

Behrendt, S. C. (2005). Women without men: Barbara Hofland and the economics and widowhood. Eighteenth Century Fiction, 17(3), 481-508. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/ecf.2005.0039.

Bloom, K. (2003). My worldly goods do thee endow: economic conservatism, widowhood, and the mid- and late eighteenth-century novel. Intertexts, 7(1), 27-47. Available at: DOI: 10.1353/itx.2003.0010.

Borman, T. (2014). Witches three. In Borman, T. (ed.). Witches: James I and the English witch-hunts. London: Vintage, pp. 64-80.

Carroll, H. (2017). The making and breaking of wedlock: visualising Jane, Duchess of Gordon, after marriage. In DiPlacidi, J. and Leydecker, K. (eds.), After marriage in the long eighteenth century: literature, law and society. Cham; Springer International Publishing, pp. 129-158.

Carr-Gomm, P. and Heygate, R. (2014). The shag-hair’d wizard of Pepper Alley: cunning-folk, girdle-measurers and the faery faith. In Carr-Gomm, P. and Heygate, R. (Eds.). The book of English magic. London: Hodder and Stoughton, pp 297-340.

Dunkley, P. (1981). The reform of the English poor laws, 1830-1834. Journal of British Studies, 20(2), 124-129. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/175640.

Floud, R. (2016). Capable entrepreneur? Lancelot Brown and his finances. Occasional Papers from the RHS Library, 14(19-41). Available at: https://www.rhs.org.uk/about-us/pdfs/publications/lindley-library-occasional-papers/volume-14-oct-2016.pdf#page=23.

Froide, A. M. (2005). Women of independent means: the civic significance of never-married women. In Froide, A. M. (ed.), Never-married: single women in early modern England. Oxford; Oxford University Press, pp. 117-153.

Gaskill, M. (2006). Witchfinders: a seventeenth century English tragedy. London: John Murray Press.

Griffin, A. (2006). Ram Alley and female spectatorship. Early Theatre, 91-97. Available at: https://earlytheatre.org/earlytheatre/article/view/731/794.

Hanson, E. (2005). ’There’s meat and money too’: rich widows and allegories of wealth in Jacobean city comedy. ELH, 72(1), 209-238.

Harley, J. (2019). Pauper inventories, social relations, and the nature of poor relief under the old poor law, England, c.1601-1834. The Historical Journal, 62(2), 375-398. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X18000043.

Hodgson, O. (c.1835-c.1840). Hodgson’s Genuine Patent Medicines: Widow Welsh’s Pills. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1951-0411-4-69. [Accessed 10 January 2024].

Knapp, V. J. (1997). The democratization of meat and protein in late Eighteenth‐ and nineteenth‐century Europe. The Historian, 59(3), 541-551. Available at: DOI: 10.1111/ j.1540-6563.1997.tb01004.x.

Laurence, A. (2008). Women and finance in eighteenth-century England. In Laurence, A., Maltby J. and Rutterford, J. (eds.). Women and their money: 1700-1950. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 30-32.

McIlvenna, U. (2016). Ballads of Death and Disaster: The Role of Song in Early Modern News Transmission. In Spinks, J. and Zika, C. (Eds.), Disaster, Death and the Emotions in the Shadow of the Apocalypse, 1400–1700. London; Springer. Available at: DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-44271-0_13

National Archives (2023). Currency Converter: 1270-2017. [Online]. The National Archives. Available at:

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/. [Accessed 7 December 2023].

Nickerson, R. (2018). The formidable widow: a comparison of representations and life accounts of widows in early seventeenth-century England. The General: Brock University Undergraduate Journal of History, 3, 191-205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26522/tg.v3i0.1695.

Orser, C. E. (2011). The archaeology of poverty and the poverty of archaeology. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 15(4), 533-543. Available at: DOI: 10.1007/s10761-011-0153-y.

Peters, C. (1997). Single women in early modern England: attitudes and expectations. Continuity and Change, 12(3), 325-345.

Ross, M. E. (1992). Le deuil et le problème du paraître chez la veuve comique du début du dix-huitième siècle. [Mourning and the problem of appearance for the comic widow at the beginning of the eighteenth century]. Neophilologus, 76(1), 41-50. Available at: DOI: 10.1007/BF00316755.

Shields, S. (2021). ‘An old maid in a house is the devil’: single women and landed estate management in eighteenth-century England. Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 44(4), 423-438.

Sivewright, J. and Sivewright, J. (1818). Lottery Handbill. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1862-1217-125. [Accessed 19 November 2023].

Smith, J. E. (2008). Widowhood and ageing in traditional English society. Ageing and society, 4(4), 429-449.

Spicksley, J. (2008). Usury legislation, cash, and credit: the development of the female investor in the late Tudor and Stuart periods. Economic History Review, 61(2), 277-301. Available at: DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2007.00402.x.

Tegg, T. (1803). The Widow Waddle of Chickabiddy Lane. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_18 72-1012-4914. [Accessed 19 November 2023].

Todd, B. J. (2010). Property and a woman’s place in restoration London. Women’s History Review, 19(2), 181-200.

Whittle J. and Hailwood, M. (2020). The gender division of labour in early modern England. Economic History Review, 73(1), 3-32. Available at: DOI: 10.1111/ehr.12821.

Appendix

Please find here further examples of both the stereotypical satire of widows in Early Modern England, but also adverts and other printed media who do not conform to this stereotype. They range from varying time frames, with a small explanation accompanying each.

Article’s cover figure:

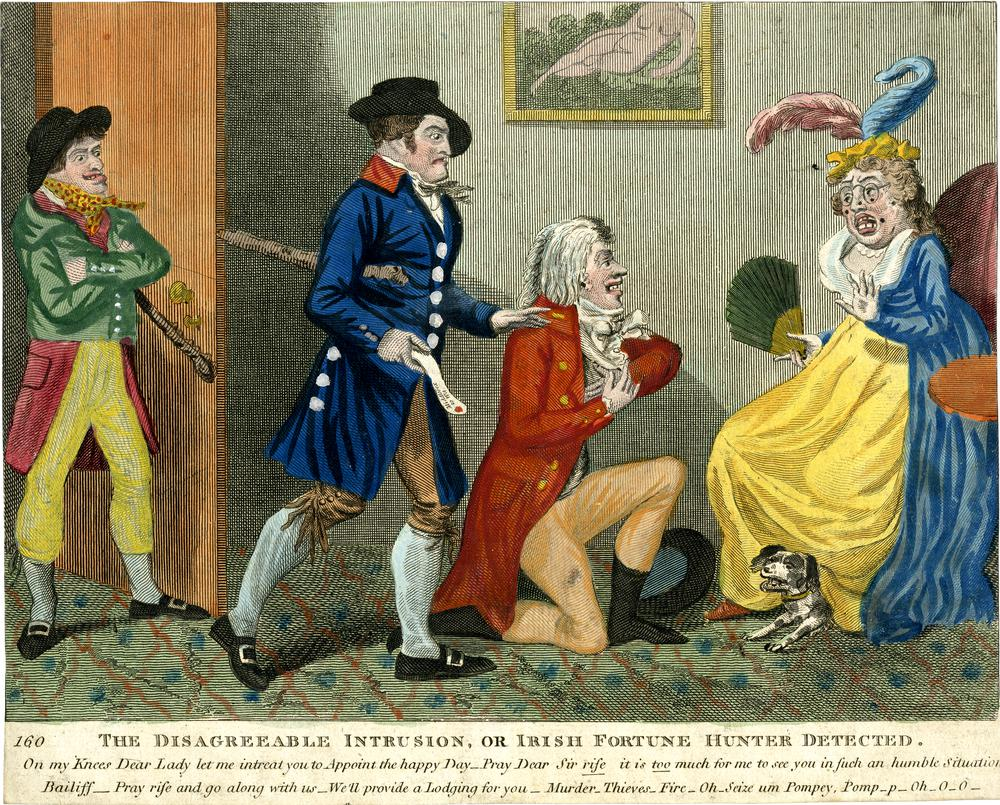

A young woman jumps into the air in sheer horror as a man throws himself to his knees before her. The detail around the young woman’s eyes is particularly comical, and the vase about to break only adds to the sense of unerupted chaos just teetering in suspense. Although not a widow (instead a single woman, presumably on the verge of becoming a spinster), the woman here is still mocked as being improper and masculine, as she is clumsy and unaware of her surroundings, being almost genuinely afraid of marriage – she is not what an accomplished 19th century woman should be.

Here we see the Biblical Patriarch Elijah, who has just brought the son of a widow back to life (1 Kings 17: 17-24). He carries him down the stairs, towards his thankful and pleading mother. Note how the widow is not caricatured or mocked, but is represented in a realistic fashion. This most likely due to the inclusion of a Biblical Patriarch, and the reverence this would demand of the designer.

This is a more stereotypical view of a satire of an Early Modern Widow. She’s sat, ugly and pox-marked, as a potential suitor vies for her affections. This print is not only satirising the view of widows, but also the men who ‘fortune hunt’ by marrying them.

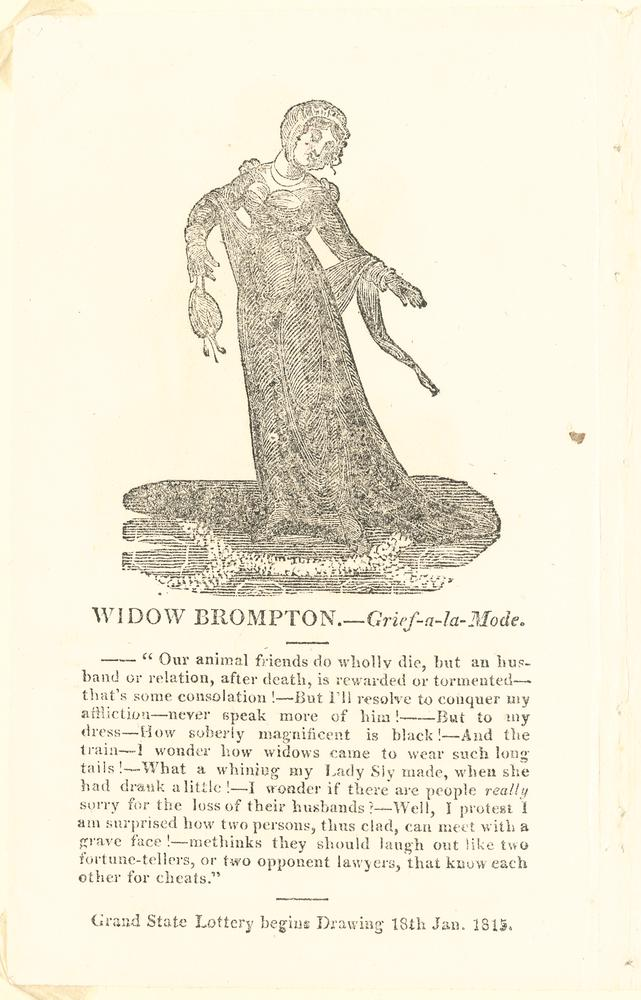

This lottery advert uses the popular character of Widow Brompton from Steele’s Grief-a-la-mode (1701). It can be seen how this advert was both aimed at widows, but also satirised the act with the soliloquy from Widow Brompton.

The man in the sailor’s uniform is Widow Mahoney’s husband, with the man next to him being ‘Widow’ Mahoney’s new fiancé. Widow Mahoney is (perhaps unsurprisingly) rather shocked to find her husband alive, and he is angry that she’s remarrying when she isn’t a widow. The vicar presiding over the wedding seems suitably bemused. Note how Widow Mahoney is fat and ugly, and her husband-to-be is a little weedy and effeminate, almost as if their roles have been reversed.

Appendix Bibliography

Anonymous (1795). The disagreeable intrusion, or Irish fortune hunter detected. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1985-0119-335. [Accessed 14 December 2023].

Brown, F. M. (c.1865-c.1880). Elijah and the Widow’s Son. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1913-0415-201-663. [Accessed 14 December 2023].

Buss, R. W. (1839). Untitled. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1858-1209-38. [Accessed 14 December 2023].

Cruickshank, G. (c.1813-c.1815). Widow Brompton – grief-a-la-mode. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/C_CIB-52509. [Accessed 14 December 2023].

Gauci, M. (1850). Widow Mahoney: a comic song. [Online]. The British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1865-1111-2157. [Accessed 14 December 2023].

King James Bible (1611). New York: Harper Collins.