The Emotion of Anna Komnene: Feeling in the Alexiad

Introduction

Many historical sources from the Middle Ages are supremely focused on subject matter. Chronicles and hagiographies spill much ink about the great figures of history and the details of their lives. This focus on subject matter is similarly important in Byzantine sources. Many texts were commissioned by emperors or public figures to record the history of Rome in the east.

One such history stands out. The Alexiad was written to chronicle the life and times of the Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, imperial sovereign of the Eastern Roman Empire from 1081-1118. This was a time when the empire was balanced on a knife edge. Following a disastrous defeat at the battle of Manzikert in 1071, the empire had been experiencing a period of civil strife, economic privation, and a string of Imperial pretenders on the throne. Alexios I, an important general under the previous emperor, seized the purple mantle by force, and in 1081, took the helm of an ailing government, beset on all sides by enemies, heretics, and intrigue.

The Alexiad was written by Anna Komnene, the first daughter of Alexios I with his wife Eirene Doukaina. She had an educated upbringing, and her closeness to Alexios and the Imperial court lends important perspective to her writing. She often recounted events in The Alexiad that she had personally witnessed. Her strong connection to her father and others, meant it was emotionally charged. Herein lies the importance of this work. Whilst we can search through The Alexiad for facts, figures, and historical details, its true value comes in the personality Anna conveys. There are few occasions where a historian can fully empathise with a historic figure, even a fellow historian like Anna herself. The Alexiad allows us to feel that empathy and understand the mental state and cultural values of a member of the Byzantine aristocracy. Those who look at history as text on a page, or as a series of dates and historical accounts, lose its true value; emotion and feeling connect us with the past. We are well connected indeed with Anna reading her personal and wide-reaching words. This article seeks to not only understand her work as a historical source, but also to understand Anna herself.

Anna Komnene: Discovered through her work

Born in 1083 in the purple porphyra birthing room of the Imperial palace, Anna was first born of Alexios I Komnenos with his wife Eirene Doukaina. Both families had a rich tradition of Imperial ancestors and presence at court. Anna was the product of an intensely political union. This placed her at the heart of Roman politics. Being the first born, she stood to inherit the throne after her father’s death. Previous female Byzantine rulers such as Zoe (1042) and Theodora (1042, 1055-56) show that this was a very real possibility. Women in Byzantium were powerful and held many more rights and authority than in the west. Anna was quickly betrothed to Constantine Doukas, a descendent of the previous Emperor Michael VII. This would ensure a strong succession in a time where the empire had been plagued by usurpers and military coups. Anna had the weight of the world on her shoulders from a very young age.

She was well educated in her mother’s household, writing in The Alexiad that she was taught the quadrivium of sciences (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music). She seemed to be taught beyond the standard, often expressing her knowledge of scripture and philosophy. Her mother Eirene was a great scholar of religious texts and this knowledge was passed down to Anna along with a desire to educate herself as much as possible. Anna’s writings often wander into her own life and perspective in The Alexiad. We can use this to learn a few things about her: she loved her father. When Anna describes the occasion of her own birth, she notes that her father was on campaign at the time. Her mother begs she wait in the womb for Alexios’ return. Thus, she waits. Anna sees this as a clear sign of love and obedience, even in a prenatal state. Despite her claims of historical objectivity, it is clear across The Alexiad that she greatly admired Alexios’ achievements and stoicism. When the first crusade enters Constantinople in 1095, Anna is in awe of his ability to hear petitions and bear their loutish behaviour through the night, long after his courtiers have all retired.

Her admiration for her mother is no less evident. Eirene Doukaina is portrayed as a great thinker and constant comfort to Alexios, especially in the waning years of his life. She seemed the only one who could get him to sleep. Only she could soothe the pain of an old injury. Familial love like this may be showing more than Anna’s sentiment though. The 10th century had seen a rise of noble families in the empire, and through the next century, family values and connections had become of supreme importance. This formed the basis of Alexios’ own governmental policy. Blood truly was thicker than water. Positions of authority were filled exclusively by Alexios’ relatives. Anna’s mother was named regent during the emperor’s absence, and his own brother Isaac was named sebastokrator. This wasa position at Alexios’ right hand created by him to ensure his brother remained close. Anna’s emphasis on family is not only a reflection on her own sensibilities, but a means of reinforcing Komnenian politics.

Medieval Romans differed little from ancient Romans in opinion of foreigners and outside polities. Anna echoes this often in The Alexiad, allowing us a glimpse of Byzantine xenophobia. She is expressive in her descriptions, claiming Normans and westerners to be avaricious and thick-headed, charging headlong into things without thought. The Turks receive no greater review, proclaimed “heathens” and “barbarians” often throughout Anna’s history. The Pechenegs receive a particularly poor reputation as dogs who eat their own vomit. The Alexiad often glorifies individual characters such as Bohemond of Taranto, Alexios’ Norman rival, to a near sycophantic degree. This is deceptive, however. Anna’s opinion of the Normans is wholly negative. She merely ascribes such greatness to Bohemond because it lauds even greater accolades on Alexios’ shoulders when he is victorious against him. Anna’s expressiveness shows great zeal and is typical of Byzantine views of outsiders. Alongside prejudices and ideals, Anna is greatly humanised by the pain and loss she expresses in her work. Often her intercessions in the narrative will be lamentation. She introduces The Alexiad by explaining a need to pick up historically from the work of her late husband, Nikephoros Bryennios. She married this man later in her life after her betrothal to Constantine Doukas fell through. Nikephoros died of an illness after campaigns in 1137, a loss which tortured Anna for her remaining years. Her love for Nikephoros is writ large in her prologue: ‘The kaisar’s untimely death and the suffering it brought about touched my heart deeply and

the pain of it affected the innermost part of my being.’ Her sorrow suffused her writing at many points, as she painted pictures of late nights writing. her tears mar the ink on the page as she recalls her painful youth and indelible loss. These breaks in the narrative are a departure from the accepted standard of history. The humanity they provide, however, is precious enough to praise this anomaly.

The death of Alexios in the final book of The Alexiad fully embodies this grief. Anna is inconsolable and near incapable of recording his illness and eventual death. Breaks in the text tell us she is barely able to control herself. Through all this emotion expressed, we can get a clearer picture that Anna was a human being with connections, thoughts, and aspirations. It allows us to get closer to her through the gaping chasm of history than we can with many other historical authors, dispassionate as they often are.

Emotion, Bias, and the Truth

Anna may seem very emotional, but through emotion and bias, truth begins to appear. Georgina Buckler’s book provides the opinion of a medical professional. Anna’s recount of Alexios’ death was detailed and clinical enough to fully understand the emperor’s cause of death. Despite her obvious grief, her description is still invaluable and precise. Similarly, The Alexiad provides original documents, proclamations, and letters. Though bias may have guided what she recorded, these complete documents are important historical sources.

Prose and emotional literature are one thing; it is also crucial to see the historiographical ability of an author to judge their bias. The Alexiad is styled as an epic prose, mimicking Homer’s Iliad, whilst remaining grounded in the historic and literary tradition of earlier authors such as Michael Psellos. This tradition is one of eye-witness and oral sources; any Byzantine writers, Anna included, relied chiefly on things they saw with their own eyes. Often gaps were filled only with second hand testimony from trusted and empirical sources. A contemporary writer, Cinnamus, operating under Alexios’ grandson Manuel Komnenos, says it best. He will deal only very briefly in matters he neither saw himself, nor learnt with certainty. Anna is staunch in remaining within this standard. Of course, she benefits from a unique position in the imperial court as princess, with access to imperial records and firsthand experience of what she sees. As we have explored, this is often where her emotion comes from. It is hard to be empirical when the characters in your narrative are your closest companions and family. The context in which Anna is writing is also important to understanding her emotional state.

Anna completed The Alexiad in the waning years of her life after 1143 when her nephew Manuel Komnenos was emperor. This was twenty-five years after the events The Alexiad records! Anna had attempted a coup following Alexios’ death to invest her husband Nikephoros as emperor instead of her brother John. This failed and John took the purple in 1118. Anna was writing in exile and out of favour. This reflects in her work. Paul Magdalino argues Anna was criticising the pro-Latin policy of Manuel. Her dislike of the Normans is evident, but this subtext gives the prejudice a deeper meaning. She attacked the Normans in The Alexiad partly as enemies of Byzantium, but also to scold the current emperor Manual, who had made bedfellows of them. Anna had grown older by 1143, saddened by the deaths of her father, mother, and husband. Alone in the world, exiled by her brother, and disapproving of the way the empire was going, she yearned for the halcyon days of her youth. It is clear overall that The Alexiad was a way of getting back to those days. By writing glowing accounts of Alexios and his reign, she could show the world the way she remembered them. Not as the dynastic founders that Alexios’ successors saw, but as a loving father, and strong ruler.

Conclusion

The Alexiad is a standout work of Byzantine historical literature. Written as epic prose, it speaks volumes about historical events, the culture of Constantinople and the Roman east. It provides a personally written account of the period and those involved which makes no secret of the emotions and thoughts of its author. This is the crux of it. The Alexiad ultimately is a work of reflection. All the battles and travels and stories serve to paint a clearer picture of the woman that told those stories. Anna Komnene is revealed by her work: We see her education, influenced by classic poetry and historical predecessors. We see her opinion of outsiders, her love of her family, her grief, her disapproval of Alexios’ successors. Mostly it shows us an old woman, full of heartache, treasuring the memory of a father she loved so dearly.

Written by Jamie Meade

Bibliography:

Anna Komnene, Alexiad, translated by Edgar Robert Ashton Sewter, edited by Peter Frankopan, London: Penguin Classics Press, 2009.

Buckler, Georgina, Anna Comnena: A Study, London: Oxford University Press, 1929.

Frankopan, Peter, ‘Kingship and Distribution of Power in Komnenian Byzantium’,

The English Historical Review, vol. 122, No. 495, Oxford University Press, (2007).

Ljubariskij, Jakov, ‘Why is the Alexiad a Masterpiece of Byzantine Literature?’ in Anna Komnene and her times, edited by Thalia Gouma-Peterson, New York, London: Garland Publishing, 2000.

Magdalino, Paul, ‘The Pen of the Aunt: Echoes of the Mid-Twelfth Century’ in Anna Komnene and her Times, edited by Thalia Gouma-Peterson,Garland Publishing, (New York, London, 2000).

Morrison, Susan Signe, A Medieval Woman’s Companion: Women’s Lives in the European Middle Ages, Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2015.

Images:

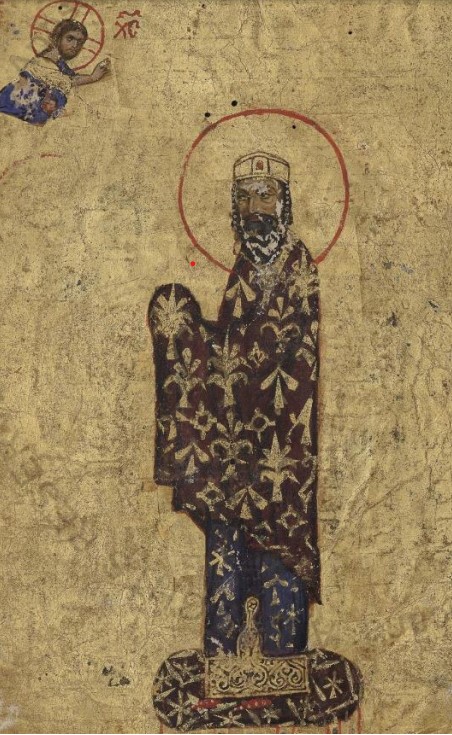

A Manuscript Depiction of Alexios I Komnenos, c. 1109-1111 (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Gr. 666, f. 2r).

Mosaic of John II Komnenos (r. 1118-1143) and his wife Irene of Hungary, Flanking the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, (Hagia Sophia, Istanbul).

A 12th century edition of the Alexiad of Anna Komnene c. 1101-1200 (BML, Plut. 70.2.), currently at Medici Laurentian Library in Florence.